The final flight of a discontinued version of Europe’s Ariane 5 rocket added four more spacecraft to Europe’s Galileo navigation constellation Wednesday, giving the multibillion-euro network enough satellites to remain on track for the start of full global service in 2020.

Launching with an older, out-of-production upper stage fed by toxic, storable hydrazine fuel, the 155-foot-tall (47-meter) Ariane 5 ES rocket ignited is Vulcain 2 main engine at 1125:01 GMT (7:25:01 a.m. EDT; 8:25:01 a.m. French Guiana time) from the Guiana Space Center on the northeastern shore of South America.

Seven seconds later, twin solid rocket boosters fired in unison to send the Ariane 5 launcher into a clear morning sky over the spaceport in French Guiana. The boosters’ steerable nozzles guided the rocket toward the northeast, and the strap-on motors burned their solid propellant and jettisoned around 2 minutes, 19 seconds, after liftoff.

Guzzling super-cold liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen at a rate of 705 pounds (320 kilograms) per second, the Vulcain 2 engine fired for nine minutes before the core stage dropped away to fall back into Earth’s atmosphere.

The Ariane 5’s upper stage Aestus engine fired moments later, burning nearly 11 minutes to reach an elliptical transfer orbit ranging more than 14,000 miles (nearly 23,000 kilometers) above Earth. After a three-hour coast, the Aestus engine reignited for more than six minutes, reshaping its orbit to reach a circular path around the planet.

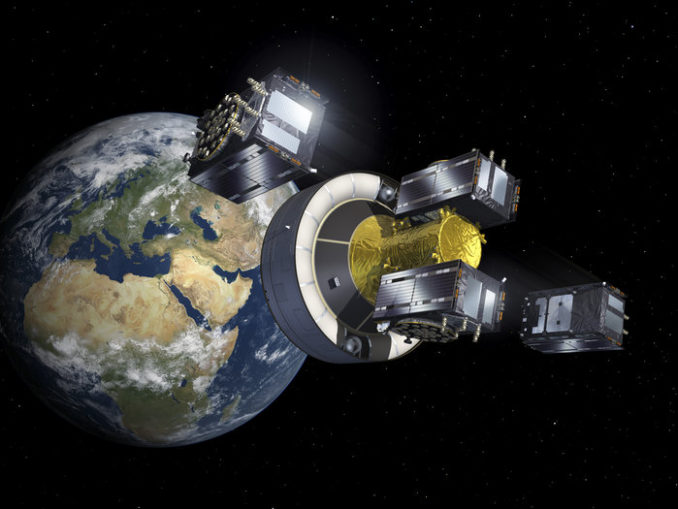

Telemetry radioed from the rocket to launch controllers in French Guiana indicated the four 1,576-pound (715-kilogram) Galileo satellites separated from their carrier module in two pairs, spaced 20 minutes apart, as intended.

A separate control team in Toulouse, France, took charge of the satellites soon after separation from the Ariane 5 rocket. Engineers there confirmed all four spacecraft were healthy after unfurling their power-generating solar panels, following a planned post-launch activation sequence.

Officials declared the launch a success, giving Europe’s Galileo navigation fleet 26 satellites, including 22 craft launched in the last four years. The 26 Galileo satellites launched to date rode seven Soyuz boosters and three Ariane 5 rockets into orbit, completing the program’s initial deployment in space.

“Today, as you saw, all the parameters were green, and the sky was perfectly blue,” said Stephane Israel, CEO of Arianespace, in a post-launch speech at the spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana. “It was an outstanding success for Europe, with 12 Galileo satellites launched in less than three years by Ariane 5.”

Wednesday’s mission was the last flight of the Ariane 5 ES version of Europe’s workhorse launcher. All future Ariane 5 launches will use the Ariane 5 ECA configuration, the most commonly-used variant of the European rocket.

The difference between the two variants is the Ariane 5 ECA flies with a hydrogen-fueled HM7B upper stage engine, which can only be ignited once in space. Missions such as Galileo satellite deployments require multiple upper stage engine firings, while most commercial satellite launches only need one.

Ariane Group, the prime contractor for the Ariane rocket family and parent company of Arianespace, is developing a new engine named Vinci for Europe’s next-generation Ariane 6 rocket. The Vinci is designed to be reignited in space.

Paul Verhoef, director of navigation at the European Space Agency, said the Galileo network remains on track for full operational capability in 2020, a milestone further cemented with Wednesday’s successful launch.

ESA is a technical and procurement agent on the Galileo program, which is managed by the European Commission, the executive arm of the European Union.

The program is projected to cost EU member states 10 billion euros ($11.7 billion) from its inception through 2020, according to the European Commission.

Elżbieta Bieńkowska, European commissioner for internal market, industry and entrepreneurship, called Wednesday’s launch an “important milestone in the history of Galileo.”

“This launch brings the constellation to 26 satellites, and really takes Galileo one step closer to its full operational capability.”

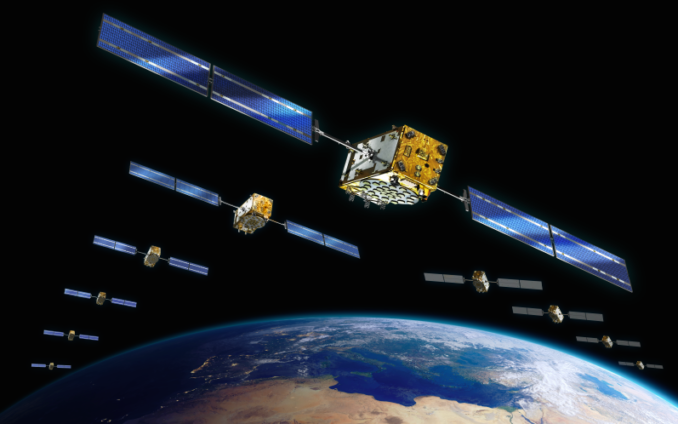

Once complete, the Galileo constellation will be made up of around 30 satellites, including 24 operational spacecraft and approximately six spares spread among three orbital planes 14,429 miles (23,222 kilometers) above Earth.

The satellites launched Wednesday are the last of a second batch of navigation platforms ordered from OHB of Germany, which builds the spacecraft, and British-based SSTL, provider of the navigation payloads.

There will be a hiatus in Galileo launches until late 2020, when the first pair of an additional 12 Galileo satellites ordered from the OHB/SSTL team by ESA and the European Commission will be ready for liftoff. The next series of Galileo satellites are expected to launch on Europe’s Ariane 6 rocket, riding two at a time aboard the lighter configuration of the next-generation launcher with two solid solid rocket boosters.

“We are happy with what we have at the moment, and with the delivery of the next batch in 2020,” Verhoef said.

Officials said the addition of the four satellites launched Wednesday — along with the eventual incorporation of two Galileo spacecraft launched into an incorrect orbit in 2014 and the activation of Galileo’s ground systems — should allow the European Commission to declare the network ready for full operations in 2020.

The European Commission kicked off Galileo’s initial services in December 2016, allowing users equipped with Galileo-enabled chipsets to incorporate Galileo navigation signals alongside those provided by the U.S. military’s GPS satellites and the Russian military’s Glonass fleet.

But without a full complement of at least 24 satellites, there are still gaps in Galileo coverage. Besides the two Galileo satellites flying in the wrong orbit, another spacecraft suffered an antenna failure and is unable to provide services.

Nevertheless, officials said those gaps will be closed in the next few years, and the satellites that are working in orbit are providing better-than-required positioning estimates.

“Not only is the Galileo performance promised to be very good, it is very good,” said Rodrigo da Costa, Galileo services program manager at the European Global Navigation Satellite Systems Agency, or GSA.

“Seven years on, we have 26 satellites in orbit,” said Jean-Yves Le Gall, president of CNES, the French space agency. “We’ve got a system that’s becoming the best in the world. We’re talking about 400 million users. The numbers are constantly increasing.

“The accuracy is tremendous,” Le Gall said in remarks after Wednesday’s launch. “With our system, we know actually which side of the street we’re on.”

Most new smartphones incorporate Galileo data alongside GPS signals in their navigation apps, and more cars are equipped with Galileo-compatible navigation systems each year, officials said. The combination of GPS and Galileo signals provider users with more accurate position and time fixes than possible with a single network.

Galileo’s full operational capability milestone planned for 2020 will come when the “the constellation is complete, fully operational, with all the ground segment,” Verhoef said.

“This is often forgotten,” Verhoef told reporters Tuesday. “The focus is always that we launch satellites, but I can tell you a lot of the deployment, in reality, is happening on the ground. All of that needs to be ready, included and working together as a system before you can declare any kind of operational capability.”

The four satellites launched Wednesday are nicknamed Anna, Ellen, Samuel and Tara, the names of children who won a European Commission painting competition.

Verhoef said engineers have resolved a problem that caused multiple atomic clocks to fail on some of the older Galileo navigation satellites. None of the clock failures have affected any satellite’s navigation capability, but some spacecraft lost redundancy in their navigation payloads.

“The clocks on the ground were repaired, and the ones on order were rectified, and we had to take a number of operational measures on the clocks in orbit,” Verhoef said, declining to provide details on the corrective actions during a pre-launch conference call with reporters.

“It was, as often happens with these things, a very small mistake, but it led to a rather big result, and you just have to dig very deep and go to the specialists in order to find what has happened,” Verhoef said. “What resulted was a short circuit internally in the clocks, and of course, after you have a short circuit, it is over, and they are dead.”

Arianespace’s next mission is scheduled for liftoff Aug. 21, when a light-class solid-fueled Vega launcher will send ESA’s Aeolus Earth science satellite into orbit to measure global wind profiles. That will be followed by another Ariane 5 mission — the 100th Ariane 5 launch — on Sept. 5 with two commercial communications satellites.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.