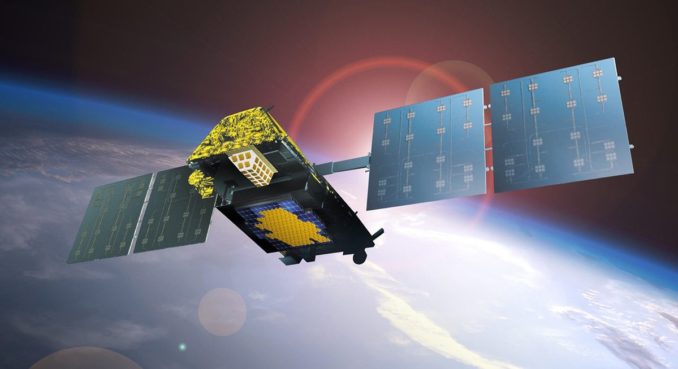

After several near-misses in tries to catch payload shrouds jettisoned from Falcon 9 rockets climbing into space, a high-speed boat tasked with retrieving the fairings for SpaceX to reuse has been upgraded and dispatched into the Pacific Ocean ahead of a launch Wednesday from Vandenberg Air Force in California.

The fairing retrieval vessel, named “Mr. Steven,” left the Port of Los Angeles late Monday heading for a position in the Pacific Ocean several hundred miles south of Vandenberg, where the two halves of the Falcon 9’s payload fairing will fall after launch with 10 Iridium voice and data relay satellites.

The fairing will split open like a clamshell around three minutes after liftoff, set for 4:39:30 a.m. PDT (7:39:30 a.m. EDT; 1139:30 GMT) from Space Launch Complex 4-East at Vandenberg, a military facility around 140 miles (225 kilometers) northwest of Los Angeles.

Each half of the fairing carries a guidance system, tiny thrusters, and a parafoil to control its descent back to Earth. Instead of having the fairing components plunge into the sea, as happens with other rockets, SpaceX wants to recover the reuse the fairing, following in the footsteps of the company’s accomplishments in recycling the Falcon 9’s first stage booster.

Mr. Steven will attempt to maneuver under one of the fairing halves, aiming to catch the composite structure with a net. A little closer to the California coast, another vessel, a drone ship named “Just Read the Instructions,” will hold position for landing of the Falcon 9’s first stage booster.

It will be the first time SpaceX will use ocean-going vessels to recover both the Falcon 9’s first stage and part of the payload fairing on the same mission. If SpaceX can snag both parts of the rocket Wednesday, it will be the first time the company has retrieved part of the fairing with Mr. Steven, and the 26th first stage booster to successfully land intact.

SpaceX has tried to catch fairings before, but none of them have fallen into Mr. Steven’s net, which engineers have nicknamed the “catcher’s mitt.”

The payload fairing protects satellites riding into space aboard SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket, keeping the spacecraft pristine and shielding satellites from weather conditions during pre-launch preparations, and aerodynamic forces during the launcher’s climb through the dense, lower regions of the atmosphere.

Once in the rarefied, nearly airless environment of space, the Falcon 9 is programmed to jettison the fairing.

So far, SpaceX has only tried to use a boat to catch the fairing during missions launched from Vandenberg, which is used for launches with satellites heading into orbits that fly over Earth’s poles. The company is expected to eventually deploy multiple vessels for fairing recoveries after launches from California and Florida.

Payload fairings from Falcon 9 launches from Cape Canaveral have also carried recovery gear, but SpaceX has not yet attempted a retrieval with a net-outfitted boat in the Atlantic Ocean.

SpaceX acknowledged the existence of Mr. Steven earlier this year, and the ship made its first known attempt to catch a fairing shell on a Feb. 22 launch from Vandenberg with the Spanish Paz radar observation satellite and two testbeds for SpaceX’s planned broadband Internet network.

During SpaceX’s last launch from Vandenberg on May 22, Mr. Steven came within about 50 meters, or 160 feet, of catching one half of the Falcon 9’s payload fairing, the company said on Twitter.

The new net on Mr. Steven is four times the size of the previous one.

“Catching rocket fairings falling from space has proven tricky, so we made the net really big,” SpaceX founder and chief executive Elon Musk wrote in a Twitter post earlier this month.

Ultimately, the fairing reuse initiative should substantially cut launch costs, according Musk.

With the latest upgrades introduced in the Falcon 9 rocket’s “Block 5” version, the Falcon 9’s fairing is “designed for full recoverability,” Musk told reporters in a May 10 conference call.

But engineers want to retrieve the fairing with a ship, rather than allowing the shroud to fall into the sea, where salt water can damage or contaminate sensitive parts.

“In future flights, we’re confident that fairing reuse will be effective, which is a big deal because each one of those fairings cost about $6 million to build, and it represents a significant percentage of the airframe of the rocket,” Musk said.

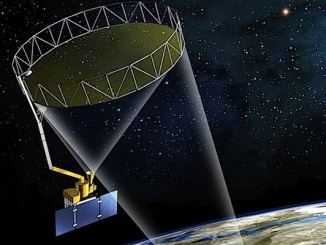

The satellites riding Wednesday’s Falcon 9 launch will push Iridium’s new-generation “Iridium Next” voice and data relay constellation to near completion.

The Falcon 9 rocket completed a hold-down engine firing at its Vandenberg launch pad Saturday, and ground crews rolled the launcher back into its hangar for attachment of the 10 Iridium Next satellites and their custom-designed multi-payload dispenser.

The fully-assembled rocket was raised vertical at SLC-4E on Tuesday, and the launch team plans to arrive on station in their control center overnight, as the countdown ticks toward a predawn liftoff at 4:39 a.m. local time.

The launcher set for blastoff Wednesday will be the third Falcon 9 rocket to feature an upgraded Block 5 first stage booster, the latest version of SpaceX’s workhouse launch vehicle, and the first Block 5 mission from California.

Wednesday’s mission will come a little more than three days after the most recent Falcon 9 mission, also a Block 5 flight, from Cape Canaveral. A Falcon 9 rocket lifted off from Florida’s Space Coast early Sunday with the Telstar 19 VANTAGE communications satellite, a powerful broadband station heading for a perch in geostationary orbit more than 22,000 miles (nearly 36,000 kilometers) over the equator.

Built by Thales Alenia Space and Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems — formerly Orbital ATK — the Iridium relay satellites fly in lower orbits, and the Falcon 9 rocket will head south from California’s Central Coast into a polar orbit.

The flight plan calls for shutdown of the Falcon 9’s second stage engine at T+plus 8 minutes, 33 seconds, followed by a 43-minute coast phase before restart of the Merlin upper stage powerplant for a nine-second burn starting at T+plus 51 minutes, 33 seconds.

Then the 10 Iridium Next satellites, which each weigh around 1,896 pounds (860 kilograms), will deploy from the upper stage at intervals of every 90 seconds. All 10 spacecraft should be separated from the rocket by T+plus 71 minutes, 38 seconds, according to a mission timeline released by SpaceX.

Wednesday’s flight is the seventh SpaceX launch to carry up Iridium Next payloads, which typically ride 10 at a time on the top of Falcon 9 rockets. The most recent Iridium satellite launch in May carried five of the company’s spacecraft, with the rest of the rocket’s capacity going toward a pair of U.S.-German climate research probes in a rideshare mission.

Ten more Iridium Next satellites are scheduled to launch later this year, bringing the total number of new-generation craft launched to 75. Six additional spacecraft are under construction by Northrop Grumman and Thales Alenia Space at a factory in Arizona to be held in reserve as ground spares.

The Iridium Next satellites provide improved global telephone and messaging services for the company’s one million subscribers, replacing an aging fleet of spacecraft launched in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.