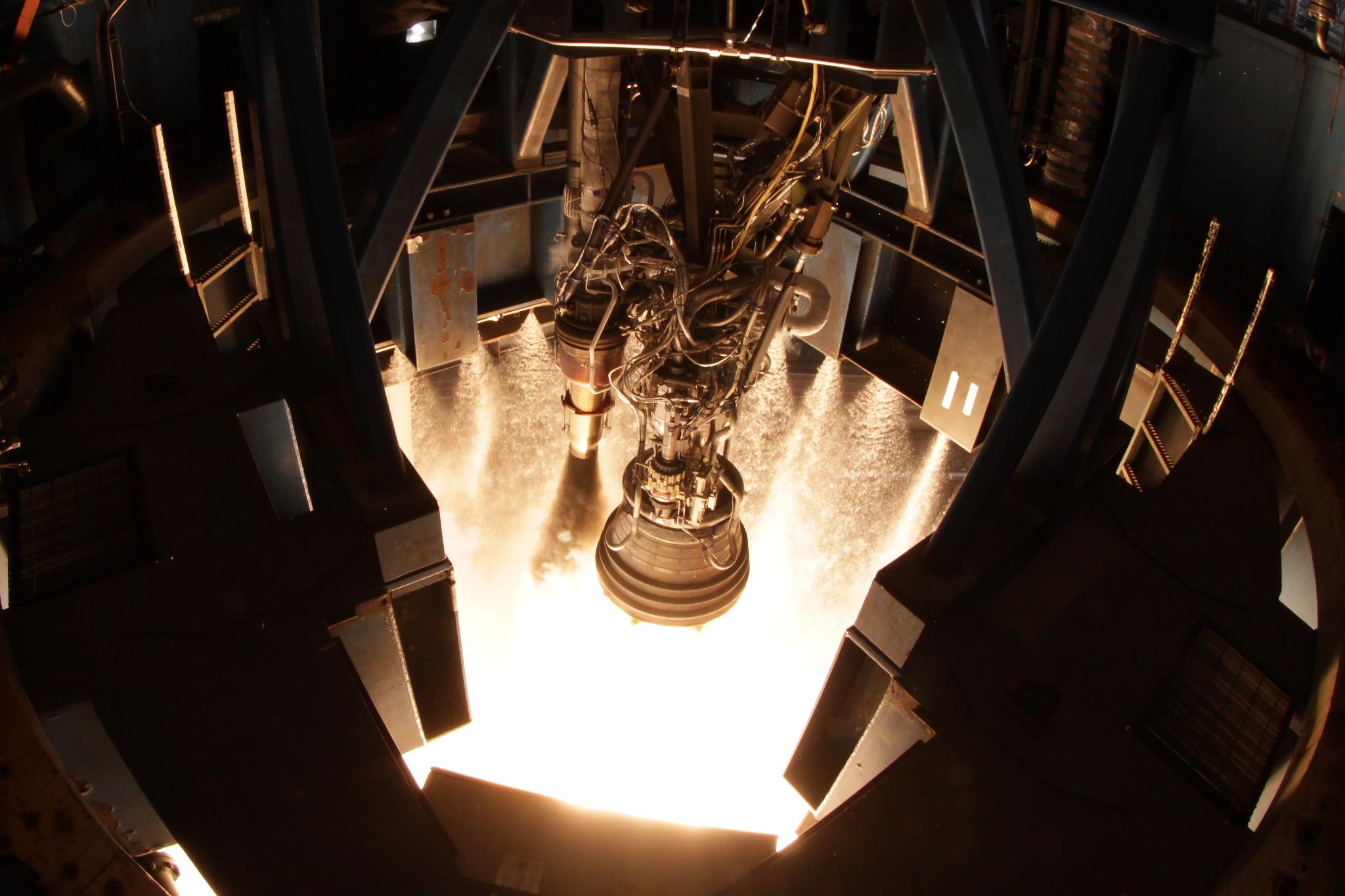

A Merlin engine designed for the version of SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket that will carry astronauts into orbit for NASA failed during testing Saturday in Texas, but the company said its upcoming launches will not be affected by the mishap.

The test engine was set for a firing at SpaceX’s rocket development facility in McGregor, Texas, but it caught fire during a leak check before ignition. The engine was a modified version of the Merlin powerplant that powers both stages of SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket.

“SpaceX experienced an anomaly during a qualification test set up of a Merlin engine at our rocket development facility in McGregor, Texas,” said John Taylor, a company spokesperson, in a statement released to Spaceflight Now on Wednesday. “No one was injured and all safety protocols were following during the time of this incident.

“We are now conducting a thorough and fully transparent investigation of the root cause,” Taylor said. “SpaceX is committed to our current manifest and we do not expect this to have any impact on our launch cadence.”

Nine Merlin engines are mounted to the base of the Falcon 9’s first stage, and a single Merlin engine powers the Falcon 9’s second stage.

SpaceX’s next Falcon 9 mission is set for launch from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida next Wednesday, Nov. 15, with a secretive payload named Zuma for the U.S. government.

Officials said the engine lost Saturday was not built to fly on a Falcon 9 rocket. It was a ground development engine for SpaceX’s “Block 5” Falcon 9 booster, which is expected to debut next year.

The test bay in which the Merlin engine was housed sustained damage in the explosion, and it will take two-to-four weeks to repair the facility, officials said. An adjacent bay has superficial damage, and could be back operational in two or three days.

SpaceX is currently building and launching an iteration of the Falcon 9 known as “Block 4.” Test-firings of Merlin engines for near-term Falcon 9 launches will continue in the other test bay.

A company spokesperson said it has notified the U.S. Air Force, NASA and the Federal Aviation and Administration of the test failure.

The Block 5 engines will produce more power and features a redesign to make the engines easier to reuse on multiple flights. The Block 5 version of the Falcon 9 will also incorporate changes to meet NASA safety requirements for launches with astronauts heading for the International Space Station.

“Block 5 is the last big spin on Falcon 9, and it’s largely driven by the upgrade that we needed to make for the commercial crew program, as well as national security space launch requirements,” said Gwynne Shotwell, SpaceX’s president and chief operating officer, during a question-and-answer session in February.

NASA awarded contracts to SpaceX and Boeing in 2014 to ferry astronauts to and from the International Space Station. SpaceX’s Crew Dragon capsule will take off on Falcon 9 rockets from the Kennedy Space Center, and the company plans an orbital test flight with two astronauts as soon as August 2018.

SpaceX engineers also added a permanent fix to resolve a concern with turbine wheel cracks inside the Merlin engine’s turbopump.

“There is a performance upgrade here as well, largely to get more margin for (those) very demanding customers,” Shotwell said in February. “There’s some manufacturing improvements. We’ve addressed the turbine wheel issue (on Block 5). There are probably 100 or so changes on that vehicle.”

SpaceX has not said when the Block 5 version of the Falcon 9 will make its first launch. Officials earlier this year suggested the Block 5 could debut by the end of 2017, but it is now expected no sooner than February.

In an interview on “The Space Show” online radio program in June, Shotwell said the Block 5 is also important for SpaceX’s ambition to reuse Falcon 9 first stage boosters more often, and at less expense. Boosters based on earlier Falcon 9 designs can be reused two or three times, but a Block 5 first stage could be reused a dozen times, she said.

Components on the Block 5 rocket, such as valves, will be requalified and redesigned at more extreme operating conditions and for longer durations, she said. Block 5 rockets will require less refurbishment between landings and re-flights, thanks to more resilient thermal protection and other upgrades.

SpaceX has launched Falcon 9 rockets 16 times this year — all successfully — after launch campaigns in 2015 and 2016 were cut short by rocket explosions.

At least three more Falcon 9 launches are planned before the end of the year. After next week’s launch of Zuma from pad 39A at KSC, another Falcon 9 rocket is set to launch no earlier than Dec. 4 from nearby pad 40 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station with a Dragon supply ship heading to the International Space Station.

Iridium’s fourth batch of 10 next-generation commercial voice and data relay satellites is set for liftoff no earlier than Dec. 22 from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California.

SpaceX says it could launch its first Falcon Heavy rocket by the end of the year. The upcoming reactivation of pad 40 at Cape Canaveral will clear the way for workers to wrap up preparations for the heavy-lift launcher at pad 39A in time to begin fueling and hold-down firing tests in December. The launch could follow soon after those tests, assuming they go according to plan.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.