The frozen faraway miniature world targeted for a high-speed flyby by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft on Jan. 1, 2019, now has a nickname: Ultima Thule.

Formally known as 2014 MU69, the robotic space probe’s next target will become the most distant object ever explored up-close, making Ultima Thule a fitting nickname.

“The name comes from medieval mapmakers, where Thule (pronounced “thoo-lee”) was a distant and unknown island thought to be the northernmost place on Earth,” wrote Mark Showalter, a member of the New Horizons science team who led the naming campaign. “‘Ultima Thule’ (which translates as ‘farthest Thule’ or ‘beyond Thule) has come to be used as a metaphor for any mysterious place ‘beyond the borders of the known world.’

“This is an apt metaphor for the tiny object, four billion miles away, that will be the next destination for the New Horizons spacecraft,” Showalter wrote in a blog post revealing the nickname.

The New Horizons team selected the monicker after seeking nominations from the public, who then ranked 37 of the potential names in an online poll. Mission managers said they would pick a nickname from among the top vote-getters, and Ultima Thule was one of the most popular nominees, officials said in a press release Tuesday.

“MU69 is humanity’s next Ultima Thule,” said Alan Stern, New Horizons principal investigator from Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. “Our spacecraft is heading beyond the limits of the known worlds, to what will be this mission’s next achievement. Since this will be the farthest exploration of any object in space in history, I like to call our flyby target Ultima, for short, symbolizing this ultimate exploration by NASA and our team.”

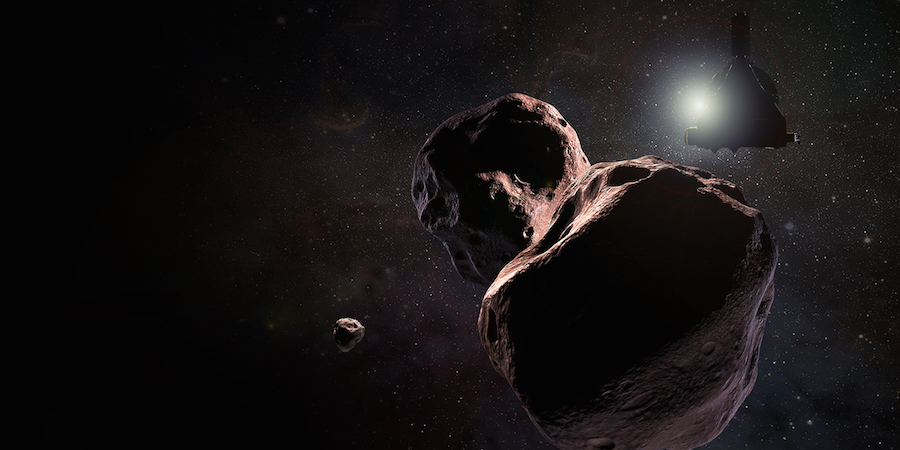

Three-and-a-half years after its historic first encounter with Pluto, New Horizons is in an extended mission. NASA approved a plan to aim the spacecraft for 2014 MU69, or Ultima Thule, a target that scientists believe could consist of two or three icy worlds orbiting in close proximity to one another in the Kuiper Belt, a zone of frozen objects orbiting the sun beyond Neptune.

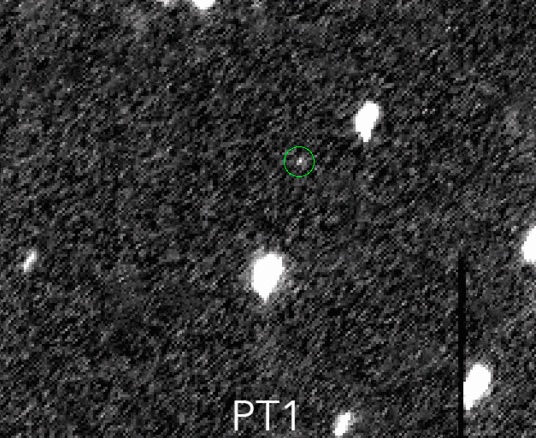

Scientists know little about Ultima Thule, which appears as a speck of light through even the highest-power telescopes, such as Hubble, the famous observatory astronomers used to find the object in 2014.

Ultima Thule is about the diameter of a large city and appears reddish in telescopic views, and a field campaign last year used occultations — when the object passed in front of stars as seen from Earth — to discern more about the shape and environment of New Horizons’ next target.

It turns out the object is probably a dual-lobe world, with its two segments either orbiting one another or a contact binary stuck together “like two globs of ice cream,” said Marc Buie, a co-investigator on the New Horizons mission from SWRI.

Buie said in December that scientists found evidence that Ultima Thule has a small moonlet lurking nearby.

Researchers believe Ultima Thule has remained in its primordial state since the solar system’s early history 4.5 billion years ago. Comets that come from the far outer solar system originated in the same frozen, faint environment, but repeated passes near the sun have erased their ancient characteristics.

Scientists hope the plutonium-powered New Horizons spacecraft’s discoveries at Ultima Thule will help their understanding of how the solar system formed and evolved over billions of years.

Ultima Thule will be just a placeholder name for 2014 MU69, which will receive an official designation from the International Astronomical Union in 2019. The New Horizons team plans to submit a formal name to the global body after the Jan. 1 flyby.

The final name will depend in part on whether MU69 is found to be a single body, a binary pair, or a cluster of multiple objects, the New Horizons team wrote in a statement.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.