A speedy space probe barreled past Pluto for a one-shot flyby Tuesday, becoming the first spacecraft to ever visit the frozen, reddish world at the solar system’s distant frontier 85 years after its discovery by astronomer Clyde Tombaugh.

Scientists celebrated the moment NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft flew by Pluto around 7:50 a.m. EDT (1150 GMT) Tuesday, but the robot explorer was on its own, presumably carrying out a series of observations of Pluto and its moons in a tightly-choreographed sequence crafted years in advance.

“Fifty years ago today, the United States was embarking at the beginning of an era of exploration of the solar system that will live forever in history,” said Alan Stern, New Horizons’ principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute. “Fifty years ago today, the first spacecraft flew by Mars. It was called Mariner 4, and I think it’s fitting that on the 50th anniversary we complete the initial reconnaissance of the planets with the exploration of Pluto.”

New Horizons — traveling nearly 31,000 mph relative to Pluto — only had a few minutes within 10,000 miles the remote world. At that speed, New Horizons traversed the nearly 1,500-mile diameter of Pluto in less than three minutes.

The probe aimed for a box centered about 7,750 miles from Pluto, and officials said a final navigation update showed New Horizons would fly about 43 miles closer to the surface, well within specifications.

Mission controllers at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland will not hear from New Horizons until around 8:53 p.m. EDT Tuesday (0053 GMT Wednesday), when the craft will pause its data collecting and radio a status message back to Earth.

Only then will scientists know the spacecraft survived the encounter.

“We’ll find out how it’s doing, whether it survived the passage through the Pluto system,” Stern said. “Hopefully it did, and we’re counting on that, but there’s a little bit of drama because this is true exploration. New Horizons is flying into the unknown.”

Managers predicted a 1-in-10,000 chance New Horizons could have a fatal collision with a speck of dust or a pebble close in to Pluto.

“I am feeling a little bit nervous, just like you do when you set your child off, but I have absolute confidence thats it’s going to do what it needs to do to collect that science, and it’s going to turn around and send us that burst of data and tell us that it’s OK,” said Alice Bowman, New Horizons’ mission operations manager.

Powered by a plutonium generator for the long journey into the solar system’s dim frontier, New Horizons arrived at Pluto after a nine-year trip from Earth with its telescopic and color cameras and composition-mapping spectrometers ready to scan the dwarf planet and its five moons.

“Stay tuned because our spacecraft is not in communication with the Earth,” Stern said. “We programmed it to be spending its time taking important data sets that it could only take today.”

Designers made New Horizons with a fixed dish antenna, so the probe is unable to transmit to Earth while spinning around to aim its camera and spectrometer apertures toward targets on Pluto and Charon.

Engineers said the instruments would collect information for storage on New Horizons’ two 64-gigabit solid-state data recorders for downlink to Earth in the coming months. It will take up to 16 months for all the data to reach Earth, streaming down at an average rate of 2 kilobits per second.

At that rate, it takes about 42 minutes for a single full-frame black-and-white image to come down from New Horizons.

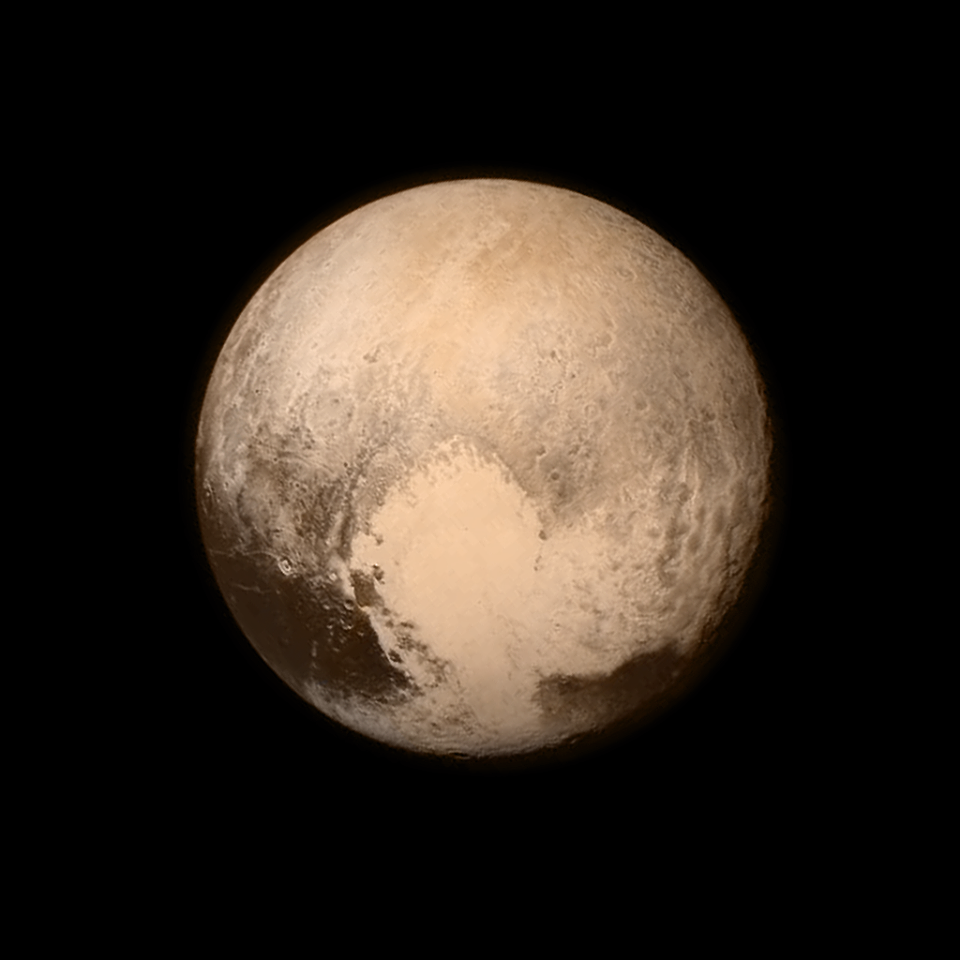

NASA released a final image of Pluto downlinked late Monday from New Horizons, showing the salmon-colored world in greater detail than ever before. Each pixel from the picture, which the spacecraft captured around 4 p.m. EDT (2000 GMT) Monday, is about 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) across, according to Stern.

That’s 1,000 times better than images taken by the sharp-eyed Hubble Space Telescope in Earth orbit.

“New Horizons took that image yesterday, and downlinked it to the ground,” Stern said. “The bits in that image flew at the speed of light for four-and-a-half hours.”

New Horizons’ black-and-white telescopic camera, named LORRI, recorded the view. Image analysts on the ground added color from data supplied by the probe’s Ralph instrument.

“The dark regions that you see are near Pluto’s equator,” Stern said. “The planet is about 1,500 miles across, to give you a scale. It’s got a thin or a rarefied nitrogen atmosphere, which you can’t see in this image because it’s clear, just like looking through other tenuous atmospheres.”

Stern said it will take more time to determine exactly what New Horizons sees on Pluto, but textures and hints of the icy world’s composition could be gleaned from color contrasts apparent in the picture.

“You can see regions of various kinds of brightness, very dark regions near the equator, very bright regions just to the north of that, a broad intermediate zone over the pole,” Stern said. “What we know is that on the surface, we see the history of impacts, we see a history of surface activity in terms of some features that we might be able to identify as tectonic, indicating internal activity in the planet at some point in its past, or maybe even its present.”

What seems to be clear is Pluto’s surface is more dynamic than Charon’s, which appears to be airless with fresh craters and dull gray markings.

“To my eye, these images show a much younger surface on Pluto and a much older, and more battered, surface on Charon,” Stern said. “I hope we’ll actually be able to (determine) the ages of different surface units on Pluto and Charon.”

Pluto’s atmosphere is about one hundred thousandth the thickness of Earth’s, and Stern said a first glance at the image shows no clear signature of clouds, hazes, or plumes erupting from Pluto’s surface.

But it is still early days in Pluto’s exploration.

New Horizons’ best look at Pluto’s climate was to come after the flyby, when the probe will monitor how radio signals passed between the spacecraft and Earth are distorted by molecules in Pluto’s atmosphere.

“We also know that this is clearly a world where both geology and atmosphere climatology play a role because Pluto has strong atmospheric cycles,” Stern said. “It snows on the surface. The snows sublimate and go back into the atmosphere each 248-year orbit. Those have been observed to move around on the surface seen from three billion miles away.”

Stern spearheaded a tumultuous effort to get a Pluto probe approved by NASA, which eventually selected the New Horizons mission concept in 2001. The $720 million mission launched on an Atlas 5 rocket from Cape Canaveral in January 2006 and reached Jupiter 13 months later, becoming the fastest spacecraft ever dispatched from Earth.

For many scientists, the wait to see Pluto took more than 25 years from the drawing board to Tuesday’s flyby.

“We haven’t all keeled over with strokes and heart attacks yet in anticipation, but some of us have gotten close,” said Ralph McNutt, a co-investigator on New Horizons’ science team who started working on a Pluto mission in the late 1980s. “These are pictures that have been a long time in the making.”

And a portion of Tombaugh’s ashes are stowed aboard New Horizons. Pluto’s discoverer will eventually be the first person whose remains will exit the solar system.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.