A weather satellite set to bring new storm tracking capabilities to the western United States and the Pacific Ocean rode into space atop a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket Thursday.

Kicking off a 15-year service life, the 11,488-pound (5,211-kilogram) robotic weather observer lifted off at 5:02 p.m. EST (2202 GMT) Thursday from Cape Canaveral’s Complex 41 launch pad.

Mounted on top of a 197-foot-tall (60-meter) Atlas 5 launcher, NOAA’s GOES-S weather satellite vaulted away from Cape Canaveral after a trouble-free countdown, keeping a launch date assigned nearly one year ago.

Sporting four Aerojet Rocketdyne strap-on solid rocket motors and a Russian-made RD-180 main engine, the Atlas 5 rocket climbed through a mostly sunny sky, darting through puffy clouds and leaving a twisting exhaust plume in its wake as the launcher departed to the east from Florida’s Space Coast on 2.1 million pounds of thrust.

The Atlas 5 surpassed the speed of sound in 35 seconds, and its four solid rocket boosters burned out and jettisoned at T+plus 1 minute, 50 seconds. About a minute-and-a-half later, the Atlas 5’s nose cone, built by Ruag Space in Switzerland, jettisoned as the rocket soared above the aerodynamic friction from the dense lower layers of the atmosphere.

Burning almost a ton of kerosene and liquid oxygen propellant per second, the RD-180 engine continued firing until nearly four-and-a-half minutes into the mission. Moments later, the booster stage dropped away to fall into the Atlantic Ocean, and an RL10C-1 upper stage engine ignited for the first of three burns on Thursday’s flight.

The first firing ended around 12 minutes after liftoff to reach a preliminary low-altitude parking orbit, and the second RL10 burn ignited 10 minutes later to propel the GOES-S weather satellite into an elliptical transfer orbit ranging more than 20,000 miles above Earth.

The battery-powered Centaur upper stage coasted three hours, rising in altitude until it reached a predetermined point thousands of miles over Australia, where the RL10 engine reignited for a 95-second maneuver to nudge the GOES-S satellite closer to the equator.

An engineer monitoring telemetry from the rocket announced separation of the GOES-S satellite from the Centaur stage at 8:34 p.m. EST (0134 GMT), prompting applause inside the Atlas Space Operations Center at Cape Canaveral.

Video from an on-board camera replayed through a Guam ground station showed the GOES-S spacecraft, manufactured by Lockheed Martin, deploying from the Centaur stage.

The GOES-S weather satellite has partially extended its solar array, as planned, after an on-target launch on an Atlas 5 rocket. Here’s an on-board camera view of spacecraft separation. https://t.co/Gr9v5Uujoy pic.twitter.com/3pLcWjn7CS

— Spaceflight Now (@SpaceflightNow) March 2, 2018

Ground controllers confirmed the GOES-S spacecraft completed a partial extension of its solar arrays, as planned, shortly after release from the Atlas 5 rocket in an on-target orbit.

Data transmitted from the Atlas 5 indicated it placed GOES-S in an orbit between 5,095 miles (8,200 kilometers) and 21,928 miles (35,289 kilometers) in altitude, tilted at an angle of 9.5 degrees to the equator.

Those parameters amounted to a near-perfect bullseye.

“This was smooth,” said Tim Dunn, NASA’s launch director for the GOES-S mission. “They don’t all come this way, but when they do, we truly appreciate them.”

NASA provides launch and spacecraft expertise for NOAA’s weather satellites.

Thursday’s mission marked the 76th successful flight by an Atlas 5 rocket in the same number of tries, and the 147th success in a row for an Atlas-Centaur launcher since 1993.

“Thank you to our partners at NASA and NOAA for the outstanding teamwork, as we delivered this next-generation satellite to orbit,” said Gary Wentz, ULA vice president of government and commercial programs. “We are proud to serve as the ultimate launch provider, continuing our dedication to 100 percent mission success.”

But the fiery launch from Florida’s Space Coast was just the beginning for GOES-S, which will spend the coming months moving into its final orbital perch, completing checkouts, and finally entering service later this year.

The satellite will join a sister observatory, GOES-16, launched in November 2016 and now providing real-time weather imagery over the Atlantic Ocean, the Caribbean Sea and the eastern United States.

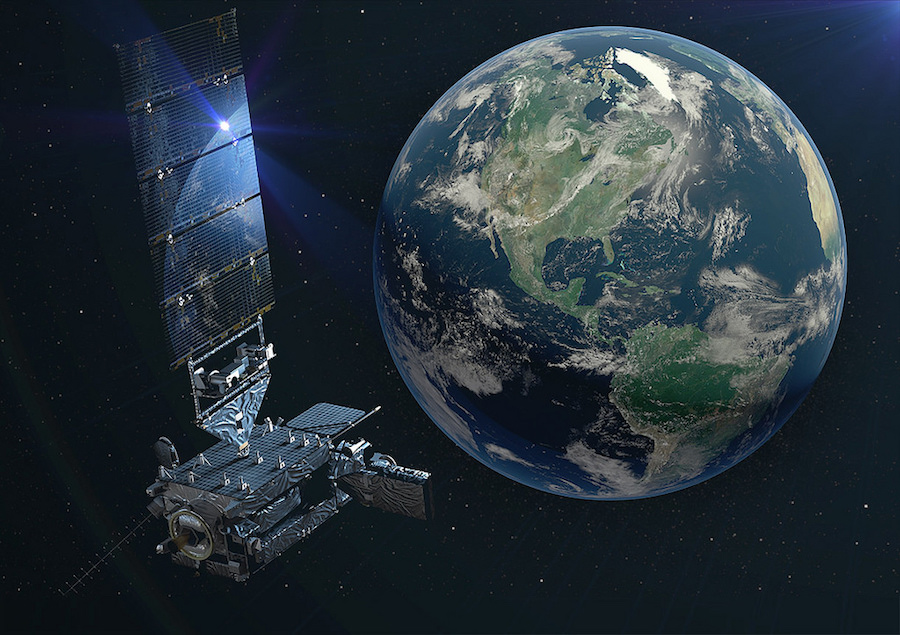

The twin spacecraft, the first two in NOAA’s GOES-R series, each carry six instruments to monitor weather on Earth and in space, including an imager that can see more detail and collect pictures more rapidly than NOAA’s past weather satellites.

GOES-S’s on-board engine, built by the Japanese company IHI, will fire six times over the next 10 days, beginning Saturday, to nudge the satellite toward its geostationary orbit destination. A final maneuver 14 days after launch will stop the satellite’s orbital drift over the Americas, setting up for a series of tests at a position at 90 degrees west longitude.

The power-generating solar panel will be fully extended around 12 days after launch, once GOES-S reaches its planned circular orbit nearly 22,300 miles (35,800 kilometers) over the equator.

At that altitude, GOES-S’s speed will keep pace with Earth’s rotation, allowing it to hover over the same place on the planet day and night.

The satellite’s X-band antenna will be deployed 18 days after launch, and an auxiliary S-band and L-band antenna wing will be extended 19 days after liftoff, according to Tim Gasparrini, GOES-R program manager at Lockheed Martin.

The boom holding GOES-S’s magnetometer instrument will be deployed 20 days after launch, and then controllers will begin configuring the satellite’s weather instruments for observations, including a month of outgassing to ensure the sensors are free of contaminants that might have been carried from Earth.

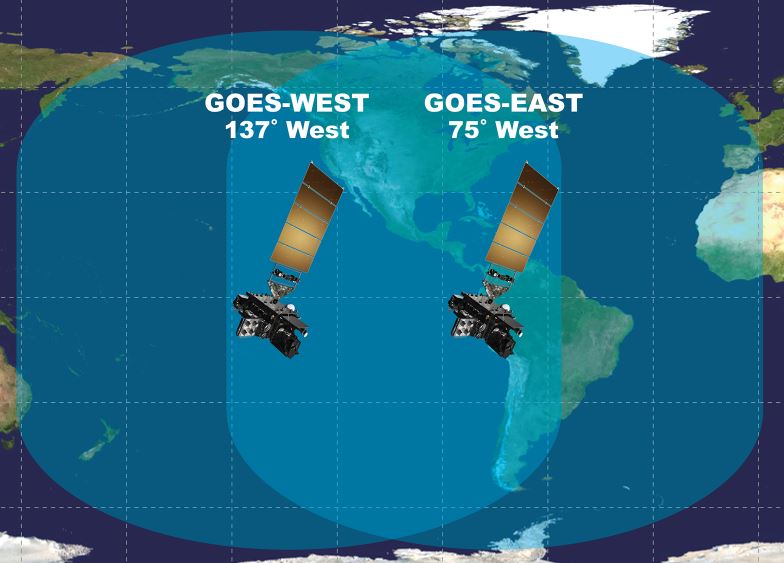

Tim Walsh, acting director of the GOES-R program at NOAA, said the new weather satellite will be ready to move to its final operating post at 137 degrees west longitude around six months after launch to begin tracking storms over the western United States, including Alaska and Hawaii, and Latin America.

Once in geostationary orbit, NOAA will rename GOES-S as GOES-17.

“GOES-S, our latest and greatest, will complete the implementation of high-resolution coverage of the entire country, delivering better observations faster than ever before. GOES-S will become GOES-West and keep an eye on the weather patterns that impact the West,” said Joe Pica, director of the National Weather Service’s Office of Observations.

The GOES satellites, launched in series since 1975, are the “backbone of weather and climate forecasts,” said Stephen Volz, director of NOAA’s satellite and information services.

Imagery from the GOES satellites are featured in weather broadcasts and used as a primary forecasting tool by meteorologists across the Western Hemisphere, helping track tropical cyclones and tornado-spawning severe storms, plus monitoring for snow and ice cover, wildfires and fog that threaten transportation and property.

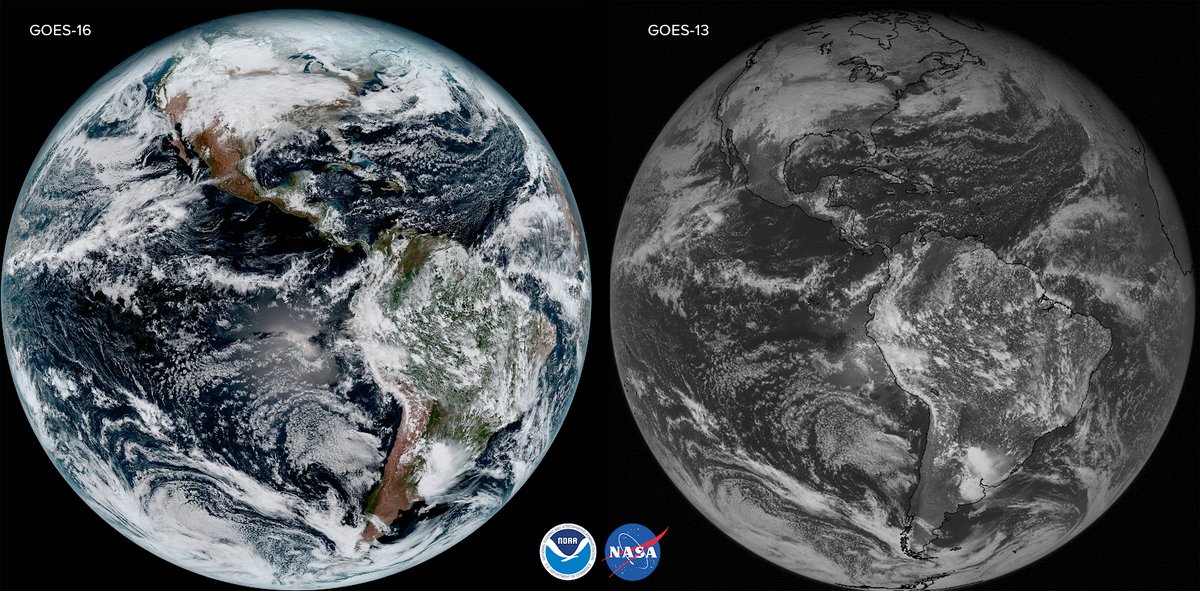

The newest family of GOES satellites, beginning with GOES-16 launched in 2016, offer a “quantum leap” in capability over NOAA’s earlier generations of geostationary weather observatories, Volz said in a briefing with reporters Tuesday.

The Advanced Baseline Imager on the latest four GOES satellites can return scans of an entire hemisphere once every 15 minutes, half the time needed by one of NOAA’s earlier geostationary spacecraft. The imager can scan the continental United States once every 5 minutes.

The new ABI-equipped satellites can return pictures of hotspots like hurricanes at a cadence of once every 30 seconds, an improvement from the five-minute rapid scans available today.

“These satellites are giving us the ability to look at storms as often as every 30 seconds, allowing forecasters to see storms as they’re developing instead of as they’ve already happened,” Walsh said.

The imager, built by Harris Corp. in Fort Wayne, Indiana, can simultaneously scan the broader hemisphere in its field-of-view and capture close-up views of individual storm systems, giving forecasters refreshed views of hurricanes and tornado outbreaks.

The ABI can see in 16 visible and infrared channels, yielding deeper insights into moisture levels and cloud types unavailable with previous weather satellite images. Earlier GOES satellites had imagers sensitive to five different parts of the light spectrum.

The upgrade allows meteorologists to distinguish between snow, fog, clouds, volcanic ash, and other particles suspended in the atmosphere.

“GOES-16, even beyond its spectacular imagery, is already proving to be a game changer with much more refined, higher quality data for faster and more accurate weather forecasts and warnings,” said Ajay Mehta, acting deputy assistant administrator for systems at NOAA’s satellite and information service. “This means more lives are saved and better environment intelligence for state and local officials, who, for example, may need to make decisions about when to call for evacuations ahead of life-threatening wildfires.”

“The ABI, one of the instruments, is able to detect small fires before they get too large, sometimes before people even dial 911,” said Dan Lindsey, senior science advisor to the GOES-R program at NOAA.

“National Weather Service forecasters will use GOES-S to monitor atmospheric, river and estimate rainfall associated with the most intense storms,” Pica said. “It wil help us track plumes from volcanic eruptions and see more clearly the total evolution of Pacific Ocean tropical storms.”

Before officials declared it operational, GOES-16 recorded detailed views of powerful hurricanes last year churning in the Atlantic Ocean, the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea.

GOES-16 tracked movements of Hurricane Harvey as it approached the Texas coast and dropped inundating rainfall over Houston, then watched as Hurricane Irma struck Florida and Hurricane Maria made a devastating landfall in Puerto Rico.

NOAA made GOES-16 operational in the so-called “GOES-East” position at the equator over 75 degrees west longitude in December.

The new GOES imager is sensitive enough to chart fog building and dissipating near airports, helping air traffic controllers route airplanes around bad visibility.

“The new satellite will augment observations over the Pacific Ocean and around mountain ranges where radar coverage is limited or blocked,” Pica said. “Marine forecasts will improve with GOES-S high-resolution imagery as we see features in the atmosphere and ocean that previous instruments did not allow. Combining these images with rapid updates every 30 seconds will help us predict storm systems more accurately and in real time.”

GOES-S will also get a better look at ice flows and other seasonal weather patterns in Alaska, officials said, allowing forecasters there to use more GOES satellite data in their daily outlooks. In the past, forecasters in Alaska could not count on the highest-quality imagery from GOES satellites because of their oblique viewing angle from equatorial orbit.

Like its predecessor already in space, GOES-S carries a detector to locate in-cloud, cloud-to-cloud and cloud-to-ground lightning strikes day or night, giving weather forecasters an inventory of the location, frequency and intensity of lightning activity that could help warn the public of severe storms.

The lightning detector on GOES-16 has pinpointed 13 billion lightning strikes since its launch less than 16 months ago.

Other instruments on GOES-S will look at the sun and chart solar radiation output and solar flares, which affect conditions in Earth’s upper atmosphere and generate geomagnetic storms, leading to possible disruptions in communications, navigation and electrical infrastructure.

An ultraviolet solar camera fitted to a telescope on GOES-S will take full disk images of the sun.

A magnetometer and space environment sensor will measure particles and electric fields in space, providing data on charging conditions that could damage other satellites.

GOES-S also hosts a transponder to receive faint distress beacons anywhere on Earth that is visible to the spacecraft. The signals will be relayed to search-and-rescue forces on the ground.

With two modernized satellites in geostationary orbit, NOAA officials said forecasters from New Zealand to West Africa, and from Canada to Patagonia, will have a critical new tool at their fingertips. A pair of Japanese Himawari satellite launched in 2014 and 2016 carry the same type of advanced imager as the new GOES craft, extending the improved coverage into the Asia-Pacific region.

Two more satellites in the GOES-R program — GOES-T and GOES-U — are in assembly at Lockheed Martin’s factory in Denver for launches in 2020 and 2024.

NOAA has budgeted $11 billion for the program, a figure that includes the four spacecraft, weather instruments, launch services and ground systems.

Gasparrini said the build-up of the GOES-T satellite is well underway in Denver, and pieces of the GOES-U satellite are arriving. Officials intend to finish both spacecraft as soon as possible to keep the assembly line going without disruption, and GOES-U will likely go into storage for a few years before its launch.

Launchers for the GOES-T and GOES-U missions have not been selected by NASA, but ULA and SpaceX are expected to compete for the contracts.

The quartet of new GOES satellites replace a previous generation of weather observers built by Boeing and launched between 2006 and 2010. The GOES-R series should keep NOAA’s geostationary weather satellites active through 2036.

NOAA also has a fleet of polar-orbiting weather satellites circling a few hundred miles above Earth, providing vital data inputs to numerical models that predict conditions up to a week in advance. The agency’s newest polar-orbiting satellite, JPSS 1, launched in November from Vandenberg Air Force Base, California.

ULA will return the Atlas 5 rocket’s mobile platform to the company’s hangar near the Complex 41 launch pad in the coming days, where ground crews will begin preparing for the workhorse launcher’s next mission from Cape Canaveral set for launch April 12.

The next Atlas 5 launch, codenamed “AFSPC-11” will send the U.S. Air Force’s EAGLE satellite into geostationary orbit using the most powerful variant of the rocket with five strap-on solid-fueled boosters.

EAGLE hosts five military experiments, according to Defense Department budget documents, including a deployable sub-satellite named MYCROFT that will conduct an unspecified mission on geostationary orbit.

The four-hour launch period April 12 extends from 6 p.m. to 10 p.m. EDT (2200-0200 GMT on April 12-13).

The next launch from Cape Canaveral will be a Falcon 9 rocket flight expected to lift off next week from the Complex 40 launch pad with the Spanish Hispasat 30W-6 communications satellite.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.