Unimpeded by rain showers and a dark gray blanket of low clouds, an Ariane 5 rocket thundered away from a European-run space base in the jungle of French Guiana Tuesday to place four Galileo navigation satellites in orbit, an on-target deployment that should improve the location accuracy of new smartphones around the world.

The Ariane 5’s countdown ticked down to zero at 1836:07 GMT (1:36:07 p.m. EST; 3:36:07 p.m. French Guiana time) Tuesday, and ignited a hydrogen-burning Vulcain 2 main engine for a last-second health assessment. The powerful European-built launcher climbed away from its launch pad in Kourou, French Guiana, seven seconds later as two solid rocket boosters fired to push the 155-foot-tall (47.4-meter) Ariane 5 into the sky.

The rocket quickly disappeared into a cloud deck, as it rolled on a course northeast from the Guiana Space Center, following a track over the Atlantic Ocean driven by 2.9 million pounds of thrust.

The twin side-mounted boosters consumed their pre-packed solid propellant in less than two-and-a-half minutes, then dropped away from the Ariane 5’s core stage to fall into the Atlantic Ocean offshore French Guiana.

A composite shroud covering the four Galileo satellites at the nose of the Ariane 5 jettisoned just before the mission’s four-minute point, and the rocket’s Vulcain 2 main engine shut off around nine minutes after liftoff.

After staging, the upper stage lit its Aestus engine for the first of two burns, first to inject the satellites into an arcing, egg-shaped elliptical orbit. After coasting more than three hours to the Galileo network’s operating altitude more than 14,000 miles (around 23,000 kilometers) above Earth, the upper stage reignited for a six-minute firing to circularize its orbit at an inclination of 57 degrees, then deployed the four satellites in two pairs.

Ground controllers in Toulouse, France, monitored telemetry from the satellites to confirm their health after reaching orbit. Engineers confirmed all four spacecraft extended their power-generating solar panels, a key achievement that marks the start of several months of checkouts and testing before they enter operational service.

Named for the winners of a European Commission drawing contest, the Galileo satellites were manufactured by OHB in Bremen, Germany. Their navigation payloads were supplied by Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd. in Britain.

“Nicole, Zofia, Alexandre and Irina are the 19th to 22nd Galileo spacecraft orbited by Arianespace,” said Stephane Israel, the French-based launch provider’s chairman and CEO. “They will soon join their teammates in the constellation to reinforce Galileo services.”

The spacecraft, each weighing around 1,576 pounds (715 kilograms), will use their own small thrusters to climb into a slightly higher orbit nearly 200 miles (300 kilometers) above their drop-off point. The Galileo payloads were intentionally released into a lower orbit to ensure the Ariane 5’s upper stage remains well away from the satellite fleet.

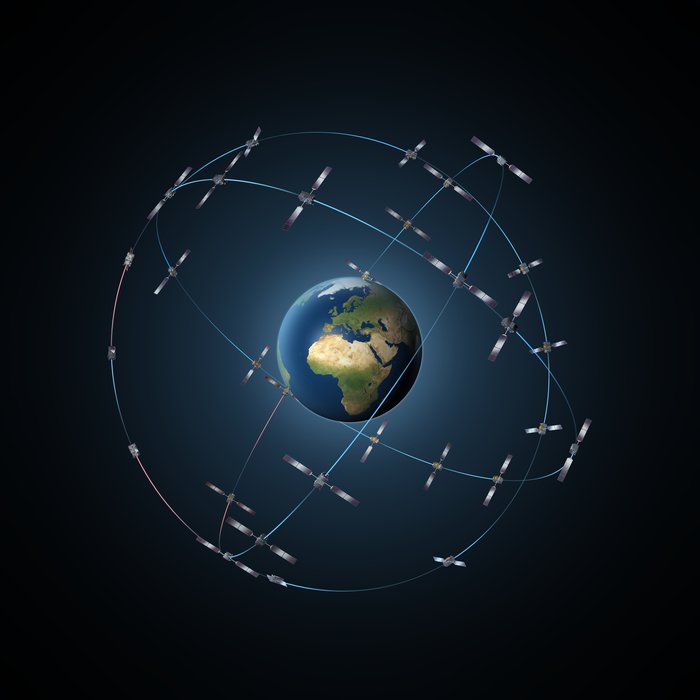

Once the new satellites are ready for service, the European Commission-owned constellation will have 22 members, 18 of which will be healthy and operational, according to Paul Verhoef, director of navigation at the European Space Agency, which acts as a technical agent and advisor for the multibillion-dollar Galileo program.

Two other Galileo satellites were launched into the wrong orbit by a Russian Soyuz/Fregat rocket in August 2014, but are otherwise functional. Officials hope a software patch that could be installed on ground receivers, including user smartphones, will eventually allow those spacecraft to officially join the active network, Verhoef told reporters before Tuesday’a launch.

Managers are not counting another two Galileo satellites in the operational fleet. One has an antenna problem, and another was purposely identified as a spare in the network, which eventually will comprise at least 30 satellites orbiting in three orbital planes.

The European Global Navigation Satellite System Agency in Prague is in charge of deciding when to declare Galileo satellites operational. The agency took charge of oversight of the navigation network in July.

“Today’s launch is another great achievement, taking us within one step of completing the constellation,” said Jan Woerner, ESA’s director general.

Four more OHB-built Galileo satellites are scheduled for launch on an Ariane 5 rocket in July 2018. Assuming the two off-position Galileo spacecraft can be counted in the network by then, the fleet could have 24 active navigation satellites by the end of next year, enough for basic global service.

But additional Galileo satellites are needed to deploy spares and replacements.

The European Commission — the EU’s executive arm — ordered 12 follow-on Galileo satellites from OHB and SSTL earlier this year for launches beginning at the end of 2020.

The European Commission and ESA in September booked two launches by Europe’s next-generation Ariane 6 rocket in 2020 and 2021 to loft pairs of the new Galileo satellites. The contracts were the first secured by Arianespace for the new Ariane 6 rocket.

Officials announced last December that Galileo navigation signals were publicly available, allowing users in cars, airplanes, and ships to receive positioning data from the European network in conjunction with information already supplied by the U.S. military’s Global Positioning System satellites.

European and U.S. officials have agreed to make current and future generations of Galileo and GPS satellites interoperable, allowing the public to receive signals from both constellations, and combine the data to render more accurate position estimates than possible with just one network.

While China and Russia have their own navigation satellite programs, neither are as seamlessly interchangeable as GPS and Galileo.

Chipsets going into nearly all next-generation smartphones, which make up the majority of navigation receivers, will incorporate both GPS and Galileo data.

“In the next few years, when people are upgrading their phones, they will have a full Galileo capacity together with GPS, and it will be jointly used, and this will facilitate an even bigger use of satellite navigation and location-based services,” Verhoef said.

Three navigation satellites must be in the sky above a user to produce a position estimate, and a fourth is needed to receive an ultra-precise timing signal, which is used in applications like ATM and credit card transactions.

“We expect that the combination of the GPS and Galileo constellations will allow an accuracy of around 30 centimeters (1 foot),” Verhoef said. “This is going to be quite a step up from a GPS-only capability (in smartphones), which is around 5 meters (16 feet). So the two cosntellations together are really going to be important.”

The latest line of GPS satellites — known as GPS 2F — were the first to include the interoperable navigation signal in L-band. The new GPS 3 satellites due to start launching next year will also have the capability.

But the Galileo network will eventually be able to support global navigation services on its own, a key factor in European governments’ decision to fund the program. The GPS fleet is run by the U.S. Air Force, while civilians manage the Galileo constellation.

“If for whatever reason, there would be a problem with either GPS or Galileo, you still have the other system you could use,” Verhoef said. “We are very happy that we have GPS as a backup, but I can tell you the Americans are very happy that they have Galileo as a backup.

The dependency on a single system has become quite a burden and a responsibility,” he said. “If, in the next years, smartphone users have all upgraded to the latest phones, we’ll have 2.5 billion users of Galileo and GPS.”

Nevertheless, Galileo was originally designed as a standalone system, and when the four satellites launched Tuesday are operational, the European network on its own will be able to provide navigation services to anyone in the world 95 percent of the time. The launch next year should make that 100 percent, but with no margin for error until spares are sent into orbit in late 2020.

Tuesday’s launch was supposed to happen earlier this year, but managers kept the satellites on the ground to repair a problem in their atomic clocks. The clocks keep precise track of time, allowing the navigation payload to measure how long it takes for a signal to travel between the satellite and a user on the ground, the key measurement needed to generate a position estimate.

Several Galileo satellites already in space have had failures in their on-board clocks, but each craft carries four of the timekeepers, giving them quadruple redundancy. No more than two clocks have failed on a single satellite, officials said.

But engineers wanted to avoid the problem on future satellites, and they pushed back the latest launch until December.

The Ariane 5 rocket lifted off Tuesday in a one-second launch window, keeping a launch appointment set more than three months ago.

Tuesday’s launch was the final Arianespace flight of the year, and the sixth by an Ariane 5 — all successful.

“This 11th successful flight in 2017 — the sixth with Ariane and the 82nd success in a row for our heavyweight vehicle — is also the last launch of the year from the CSG (Guiana Space Center),” Israel said. “Thanks to flawless operations of our launch vehicle family — six Ariane 5s, two Soyuz and three Vega — our track record for 2017 is once again outstanding.”

The next Ariane 5 launch from French Guiana is scheduled for Jan. 25 with the SES 14 and Al Yah 3 commercial communications satellites.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.