China’s first X-ray astronomy satellite launched Thursday on a mission to survey the Milky Way galaxy for black holes and pulsars, the remnants left behind after a star burns up its nuclear fuel.

The Hard X-ray Modulation Telescope will also detect gamma-ray bursts, the most violent explosions in the universe, and try to help astronomers link the outbursts with gravitational waves, unseen ripples through the cosmos generated by cataclysmic events like supernova explosions and mergers of black holes.

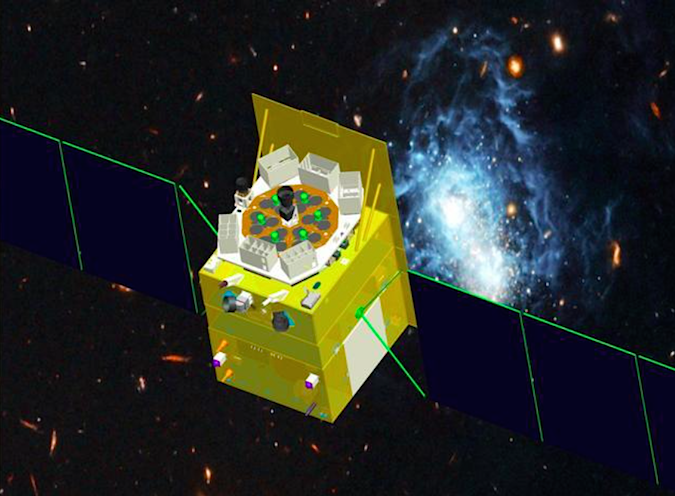

The orbiting X-ray observatory, renamed Huiyan, or Insight, following Thursday’s launch, is China’s first space telescope and second space mission dedicated to astronomy after a Chinese particle physics probe was sent into orbit in 2015 to search for evidence of dark matter.

“Before its launch, we could only use second-hand observation data from foreign satellites,” said Xiong Shaolin, a scientist at the Institute of High Energy Physics of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. “It was very hard for Chinese astronomers to make important findings without our own instruments.”

“The only way to make original achievements is to construct our own observation instruments,” Xiong said in a report by China’s state-run Xinhua news agency. “Now Chinese scientists have created this space telescope with its many unique advantages, and it’s quite possible we will discover new, strange and unexpected phenomena in universe.”

The X-ray telescope launched at 0300 GMT Thursday (11 p.m. EDT Wednesday) aboard a Long March 4B rocket from the Jiuquan space center in northwestern China’s Gobi Desert. Liftoff occurred at 11 a.m. Thursday Beijing time.

The Long March 4B booster, powered by three hydrazine-fueled stages, delivered the Huiyan telescope into a 335-mile-high (540-kilometer) orbit tilted 43 degrees to the equator, according to tracking data released by the U.S. military. That is very close to the X-ray telescope’s intended operating orbit.

Ground controllers plan to activate and test the observatory over the next five months before entering service late this year, fulfilling a mission first proposed by Chinese scientists in 1994 and formally approved by the Chinese government in 2011, according to the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The 5,500-pound (2,500-kilogram) Huiyan spacecraft is designed for a four-year mission. Its three X-ray instruments, sorted to observe low, medium and high-energy X-rays, are sensitive to 1,000 to 250,000 electron volts, an energy range that encompasses the energy of a medical X-ray.

Earth’s atmosphere absorbs X-ray light signals, so astronomers must build and launch satellites for the job. X-ray observatories are uniquely suited for studies of black holes and neutron stars, two of the densest types of objects in the universe created in the aftermath of supernovas, the explosions at the end of a star’s life.

Unlike X-ray telescopes launched by NASA and the European Space Agency, China’s Huiyan mission does not use grazing mirrors, which must be extremely flat to reflect high-frequency X-ray waves. Chinese officials said they do not have the expertise to build such flat mirrors, so scientists came up with a backup plan that does not rely on traditional imaging.

The observing method, called demodulation, “can help reconstruct the image of X-ray sources by using data from relatively simple non-imaging detectors, such as a telescope with ‘collimators’ that collects and records X-ray photons parallel to a specified direction,” Xinhua reported.

Scientists said the Chinese X-ray telescope will be able to observe brighter targets than other X-ray missions because the demodulation method diffuses X-ray light. Other telescopes reflect and focus X-ray photons onto detectors.

“No matter how bright the sources are, our telescope won’t be blinded,” said Chen Yong, chief designer of Huiyan’s low-energy X-ray instrument, in an interview with Xinhua.

“We are looking forward to discovering new activities of black holes and studying the state of neutron stars under extreme gravity and density conditions, and physical laws under extreme magnetic fields,” said Zhang Shuangnan, the X-ray mission’s lead scientist. “These studies are expected to bring new breakthroughs in physics.”

Another set of detectors on the Huiyan telescope, originally added to shield against background noise, can be adjusted to make the observatory sensitive to even higher-energy gamma rays, according to the Xinhua news agency.

The detection of gravitational waves by ground-based sensors in Washington and Louisiana opened a new door in astronomy. Created by distant collisions and explosions, gravitational waves are ripples through the fabric of spacetime, and astronomers now seek to connect the phenomena with events seen by conventional telescopes.

“Since gravitational waves were detected, the study of gamma-ray bursts has become more important,” Zhang said in Xinhua’s report on the mission. “In astrophysics research, it’s insufficient to study just the gravitational wave signals. We need to use the corresponding electromagnetic signals, which are more familiar to astronomers, to facilitate the research on gravitational waves.”

The launch of the Huiyan space telescope comes as NASA scientists turn on and calibrate another X-ray instrument recently delivered to the International Space Station.

After its launch June 3 on a SpaceX supply ship heading to the space station, NASA’s Neutron Star Interior Composition Explorer will spend the next 18 months studying the structure and behavior of neutron stars.

Three other satellites joined China’s Huiyan spacecraft on Thursday’s launch.

The OVS 1A and 1B satellites are the first two members of a commercial constellation of Earth-imaging craft for Zhuhai Orbita Control Engineering Co. Ltd. based in southern China’s Guangdong province. The two 121-pound (55-kilogram) satellites will record high-resolution video from orbit, and future spacecraft in the Zhuhai 1 fleet will collect hyperspectral and radar imagery.

The ÑuSat 3 microsatellite owned by Satellogic, an Argentine company, was also aboard the Long March 4B rocket Thursday.

Built in Montevideo, Uruguay, by a Satellogic subsidiary company, ÑuSat 3 weighs around 80 pounds (37 kilograms) and is identical to two ÑuSat satellites launched on a Chinese rocket in May 2016.

Each ÑuSat craft hosts cameras to capture imagery in color, infrared and in the hyperspectral regime, which gives analysts additional information about the makeup of objects, plants and terrain in Earth observation products. The satellites can resolve features on Earth as small as 3.3 feet (1 meter) across.

ÑuSat 3 is nicknamed Milanesat, after the traditional Argentine steak dish Milanesa. The first two ÑuSat satellites launched last year were named after Argentine desserts.

Satellogic is one of several privately-funded companies launching sharp-eyed commercial Earth-viewing satellites to collect daily images of the entire planet. The company says its satellite constellation, which could eventually number from 25 to several hundred spacecraft, will help urban planners, emergency responders, crop managers, and scientists tracking the effects of climate change.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.