The U.S. Air Force this week awarded SpaceX a contract to launch a Global Positioning System satellite in early 2019, concluding the second of as many as 15 competitions the military plans to run over the next year to pit SpaceX against United Launch Alliance for rights to lift defense and intelligence-gathering payloads into orbit.

The Air Force’s third GPS 3-series navigation satellite will launch on a Falcon 9 rocket from Cape Canaveral in February 2019, service officials said. The $96.5 million launch contract makes SpaceX two-for-two in its bids to launch high-value military satellites after the company won a previous GPS launch agreement last year.

But United Launch Alliance, operator of the Atlas and Delta rocket fleets, did not submit a bid for the earlier GPS launch contract, citing legislation in Congress threatening to restrict the use of Russian-made engines on the Atlas 5 rocket for U.S. military launches, and the Air Force’s decision to favor price over other factors in its selection criteria.

The Air Force signed an $82.7 million contract with SpaceX, the sole bidder, for the GPS 3-2 satellite after the company met minimum qualifying criteria on technical grounds. That represented a 40 percent reduction in launch cost from the Air Force’s estimated based on previous ULA flights, Lt. Gen. Samuel Greaves, commander of the Space and Missile Systems Center, said last year.

ULA is believed to have competed for the GPS launch contract awarded to SpaceX on Tuesday.

Claire Leon, director of the launch enterprise directorate at the Air Force’s Space and Missile Systems Center, said Wednesday that price was the determining factor in the military’s decision to give the latest GPS launch contract to SpaceX.

“Each contractor had to prove through their proposal that they could meet the technical, the schedule and the risk criteria,” Leon told reporters in a conference call. “SpaceX was able to do that. I wouldn’t say that they were necessarily better. They adequately met our criteria.”

The next-generation GPS 3-series satellites, built by Lockheed Martin, are expected to begin launching some time next year, several years late due to problems developing their navigation payloads and ground control systems.

The Air Force has contracted Lockheed Martin to build 10 of the new GPS 3 satellites, but a deal to manufacture the next batch of navigation platforms is being competed between Lockheed Martin, Boeing and Northrop Grumman.

The first GPS 3 satellite is set for launch aboard a United Launch Alliance Delta 4 rocket. The Air Force awarded that contract in a sole-source block buy of ULA rockets.

ULA plans to retire the medium-class, single-core version of the Delta 4 rocket in 2018 and use Atlas 5s for most of its launches through the early 2020s, when the company’s new Vulcan rocket will take over. The triple-body Delta 4-Heavy rocket will continue flying to lift the military’s heaviest satellites into orbit.

The second and third GPS 3-series launch contracts have now gone to SpaceX, giving the launch firm, led by Elon Musk, its first two awards for “EELV-class” satellites, a category that includes GPS navigation craft, nuclear-hardened, jam-resistant communications satellites, and platforms to warn the military of a nuclear attack.

The awards came after SpaceX struggled for several years to break into the military launch market, a contentious effort marked by a SpaceX lawsuit against the Air Force and intense lobbying in Washington.

Leon declined to speculate why SpaceX’s latest Air Force launch contract cost more than the last one.

“I can’t get into SpaceX’s process for pricing, however, the first award was their first time doing an Air Force EELV mission with our full mission assurance requirements,” Leon said. “I think they’re becoming more familiar with the expectations of the Air Force, so for this competition, they decided to change their price.”

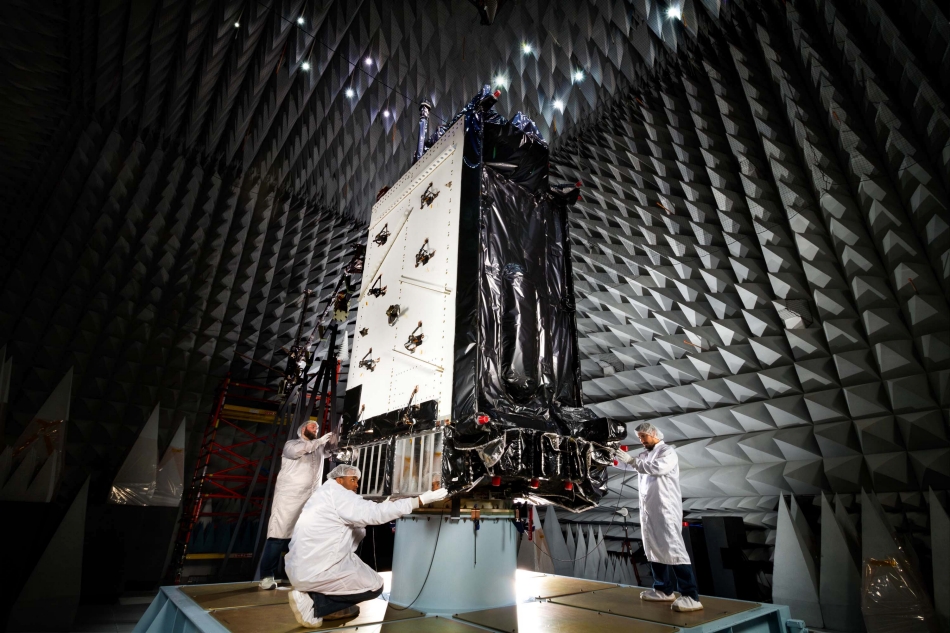

In a statement, the Air Force said the $96.5 million contract covers “launch vehicle production, mission integration, and launch operations and spaceflight certification.”

Leon said the Air Force, so far, is specifying that SpaceX only launch the military’s satellites on newly-built Falcon 9 boosters. The Air Force is risk-averse in most of their satellite programs, citing their high cost, one-of-a-kind nature, and criticality for national security.

“There’s a whole lot more work to do,” Leon said. “We would have to certify flight hardware that had been used, which is more qualification and analysis, so we’re not taking that on quite yet. I think, if it proves to be successful for commercial (missions), we might use it in the future, but at this point in time we’re not prepared to start reusing hardware.”

SpaceX plans to launch their first reused rocket on an operational satellite mission later this month from launch pad 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The flight will carry the SES 10 communications satellite into orbit, using a Falcon 9 first stage that first flew in April 2016.

Asked whether the Air Force is satisfied that SpaceX has resolved the helium system problems that led to two rocket explosions in the last two years — one in flight in June 2015 and another on the launch pad last September — Leon said: “The short answer is yes, but I’m not going to tell you that there isn’t more work to do before we have an Air Force launch.”

The Air Force’s launch procurement office at the Space and Missile Systems Center in Los Angeles is in a transition phase as launch companies prepare to debut new rockets in the next few years.

ULA’s new Vulcan rocket could launch as soon as 2019, and Orbital ATK is designing a medium-to-heavy lift rocket it says could loft commercial and national security satellites, assuming officials give a final go-ahead late this year. Both rockets are being developed as public-private partnerships between the Air Force and industry.

Blue Origin’s New Glenn rocket is also in the pipeline for a maiden flight around 2020.

Until the new rockets are certified for Air Force launches, which will not happen until they complete several successful demonstration flights, the military will award satellite launch contracts to SpaceX’s Falcon rocket family or ULA’s Atlas and Delta boosters, the only U.S. vehicles currently certified for the task.

Before SpaceX was certified, the Air Force gave launch contracts ULA in sole-source “block buy” awards.

The Air Force originally identified nine missions up for competition between ULA and SpaceX, but Leon said six more payloads have been added to the roster, extending the “Phase 1A” transition period from this year through 2019.

The nine missions previously set up for head-to-head competitions included six GPS 3 satellites, the SBIRS GEO 5 missile warning satellite, the AFSPC 9 mission, and a multi-payload launch called STP-3 for the Air Force’s Space Test Program.

Leon said six classified missions for the National Reconnaissance Office, which manages the U.S. government’s spy satellites, have been added to the list. That makes for 15 missions eligible for competition through 2019.

“SpaceX can compete for any of them,” Leon said. “They will need the Falcon Heavy for some of those competitions, so they need to get a demo flight off, at least, to be able to be competitive for some of those missions.”

The Air Force expects to award the STP-3 launch contract in June — proposals from ULA and SpaceX are already in for that mission — then release two more requests for bids by the end of the year.

According to Leon, the two new solicitations will bundle the remaining 12 missions, likely seven for the first batch and five in the second set. Launch contracts for the four GPS 3 satellites still up for competition in this procurement round might be awarded in a block to one of the launch providers, Leon said, but the others will be considered on a mission-by-mission basis, with contractors selected one at a time.

“We’re grouping them for our convenience, and for the contractors,” Leon said. “I think it will help the contractors because they’ll know what they’ve won, as opposed to doing these one at a time stretched out.”

Some of the launches up for competition will require a “direct injection” into geosynchronous orbit, a perch around 22,000 miles (36,000 kilometers) over the equator. Such missions are particularly complex, requiring a rocket’s upper stage to function at least six hours and reignite at high altitude, a capability not yet demonstrated in flight by SpaceX.

The flight sequence for GPS satellite launches is shorter because the spacecraft use on-board propulsion to reach their operational orbits around 12,550 miles (20,200 kilometers) above Earth.

“For future missions that are longer duration, there are certain steps that would have to be done to certify that,” Leon said.

The Air Force plans to assign the last three sole-source missions to ULA by the end of this year, fulfilling the final segment of an $11 billion order of 36 Delta and Atlas rocket cores from 2014, Leon said.

Those missions guaranteed to go to ULA will be the sixth Advanced Extremely High Frequency satellite, a jam-resistant telecom relay craft designed to ensure military communications in nuclear war, and two top secret NRO payloads designated NROL-82 and NROL-101.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.