Japan’s sixth HTV supply ship departed the International Space Station on Friday and headed for a destructive re-entry over the South Pacific with trash and disused batteries from the research lab, but engineers will first use the spacecraft for a pioneering experiment to investigate a new way to remove space junk from orbit.

The cargo freighter was detached from the space station’s Harmony module shortly after 6 a.m. EST (1100 GMT) Friday, then released from the lab’s Canadian-built robotic arm at 10:46 a.m. EST (1546 GMT) under the command of flight engineer Thomas Pesquet.

A series of thruster burns by the HTV will send the ship on a trajectory away from the complex.

The HTV, also nicknamed Kounotori 6, arrived at the station since Dec. 13, four days after its launch from Japan on an H-2B rocket. The spacecraft completed an automated rendezvous and delivered more than 9,000 pounds (about 4.1 metric tons) of supplies, experiments and six lithium-ion batteries to begin a refresh of the research lab’s electrical system.

While astronauts inside the station unpacked fresh food, provisions and other goods inside the HTV’s pressurized cargo module, the station’s robotic arm — under the control of engineers on the ground — pulled a pallet holding the six new batteries out of the spaceship’s external payload bay and began replacing old power packs on the starboard S4 power truss.

The batteries hold electrical charge generated by the space station’s huge solar array wings.

The battery swaps began Dec. 31, and astronauts went outside on two spacewalks Jan. 6 and Jan. 13 to secure the old batteries for disposal and long-term storage.

Twelve old nickel-hydrogen batteries were replaced on this mission — each new unit has the capacity of two old batteries — and nine of the outgoing batteries were mounted on the HTV cargo pallet for disposal at the end of the craft’s mission.

The three other disused batteries are stored on adapter plates also delivered by Kounotori 6 and now affixed outside the station.

Eighteen more lithium-ion batteries are scheduled to head for the space station on the next three HTV missions in 2018, 2019 and 2020.

Seven CubeSats carried to the space station inside the HTV’s cargo hold have been deployed since the cargo ship’s arrival. The CubeSats, primarily built by university students in Japan, were ejected from a deployer outside the Japanese laboratory module.

Four more commercial weather-monitoring CubeSats from San Francisco-based Spire Global will be deployed from the station at a later date.

The HTV’s mission is not over after its departure from the space station Friday.

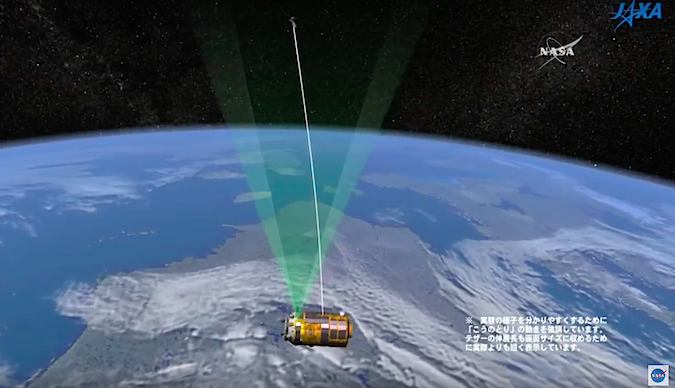

The 30-foot-long (9-meter) spaceship will stay in orbit until Feb. 5 conducting an experiment that could lay the foundation for a mechanism to remove space junk from orbit.

The spaceship will unreel a nearly half-mile-long (700-meter) tether, made of strands of thin aluminum and stainless steel wire, once at a safe distance from the space station, and scientists will monitor the device’s deployment and behavior for about seven days.

Space debris experts say electrodynamic tethers like the one carried on Kounotori 6, which has a thin coating of lubricant to encourage electric conductivity, could offer a way to de-orbit derelict rocket stages and aging satellites without expending precious propellants.

The interaction between an electrodynamic tether and the Earth’s magnetic field should generate enough energy to change an object’s orbit, eventually allowing it to burn up in the atmosphere.

Japanese ground controllers will sever the tether after about a week to keep it from interfering with the HTV’s own destructive re-entry, which will be guided by conventional rocket thrusters in a de-orbit burn. The ship will dispose of several tons of space station waste and the decommissioned nickel-hydrogen batteries.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.