NASA is taking steps to rein in costs, emphasizing bonds with private sector companies, and signaling it might be open to a future where the agency’s flagship Orion deep space capsule and Space Launch System are no longer necessary to explore deep space, at least in their current forms.

Agency officials are gauging interest from aerospace companies who could take over the building of crew capsules to carry astronauts into deep space in the 2020s, but incumbent contractor Lockheed Martin has answered with a plan to cut Orion spacecraft production costs in half.

NASA released a Request for Information in September, seeking responses from companies like Boeing and SpaceX who could replace Lockheed Martin as the Orion program’s prime contractor once its current deal expires in the early 2020s, according to a report Thursday published by Ars Technica.

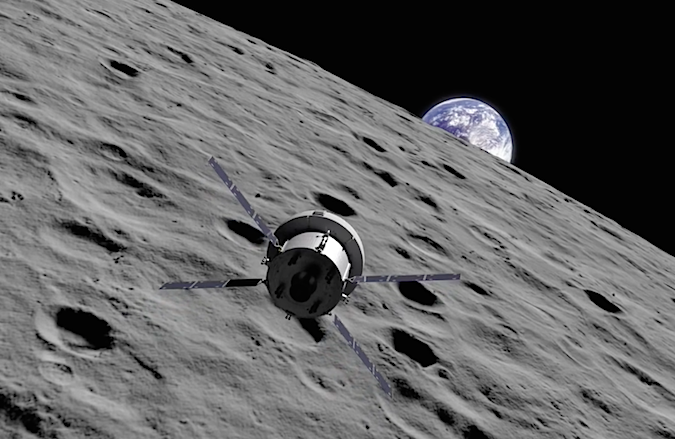

NASA wants to fly astronauts to a deep space lab around the moon, and potentially other destinations, at least once a year on the Orion spaceship, but achieving an annual flight rate without a spike in the agency’s budget requires getting the capsule’s costs down.

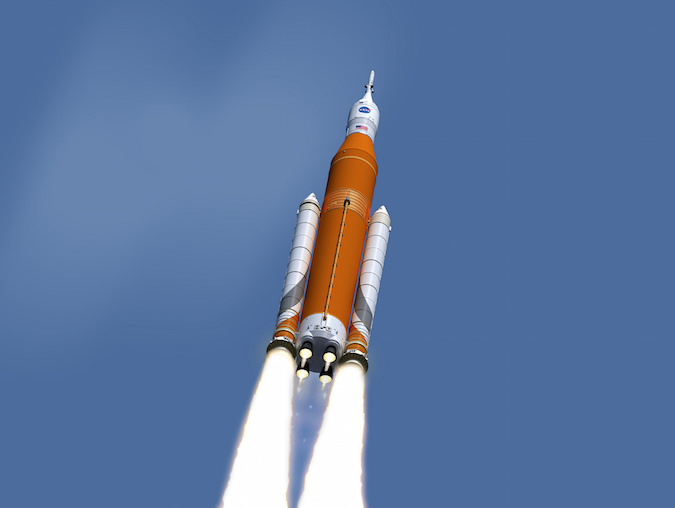

The per-flight cost of the Space Launch System, the heavy-lift rocket being crafted to send Orion capsules to lunar orbit and beyond, must also be reduced from current projections.

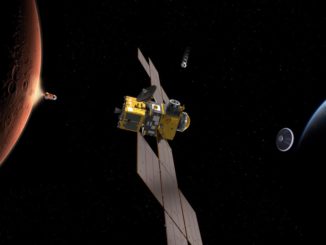

NASA officials have said realizing a $1.5 billion cost target for each mission — around $1 billion for SLS and $500 million for Orion — would allow the agency to have leftover money to develop habitats, powerful ion propulsion thrusters, and advanced closed-loop life support systems necessary to sustain human expeditions to Mars in the 2030s.

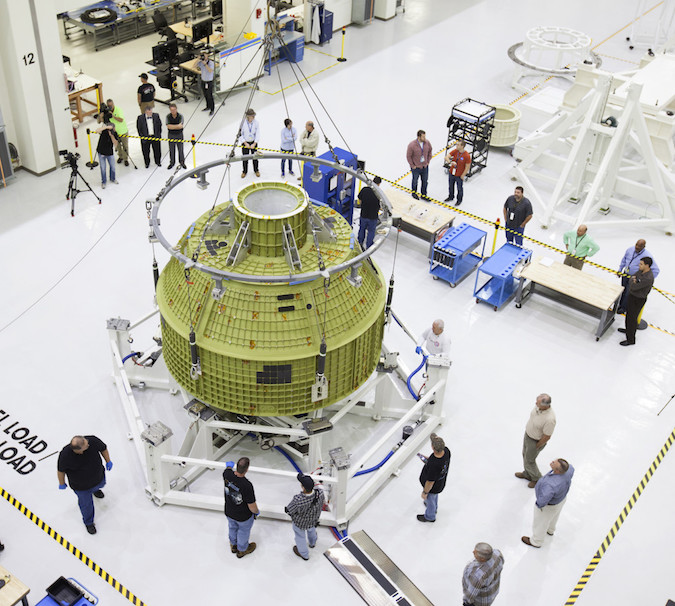

Lockheed Martin says it intends to slash the cost of building new Orion deep space capsules by at least 50 percent in the 2020s as NASA hints it might be open to alternative builders.

Cost reductions are sometimes the norm as large space projects move from research and development into operations.

A Lockheed Martin spokesperson said the Request for Information, or RFI, was part of a “routine acquisition planning process” as NASA takes decisions on production of future Orion vehicles. NASA did respond to a request for comment.

The company’s existing Orion contract with NASA, signed in 2006, only covers Orion development duties and construction of three space-worthy Orion capsules. NASA launched the first unpiloted orbital test flight of the Orion spaceship in December 2014, and another uncrewed mission is due for launch on a three-week voyage to lunar orbit in late 2018 on the maiden flight of the Space Launch System.

The test flight in 2018, named Exploration Mission-1, will be followed by Exploration Mission-2, Orion’s first trip to space with astronauts on-board, on a flight to a high-altitude lunar orbit expected to last 10-to-14 days.

NASA says EM-2 could blast off as soon as August 2021 — a best-case scenario — but have only committed to launching the mission by April 2023.

Barring any technical or funding hurdles, NASA wants to mount annual SLS/Orion missions after EM-2 to assemble a deep space research complex, visit an asteroid pulled into orbit around the moon, and eventually send humans to Mars orbit around 2033.

“The NASA and Lockheed Martin team are approaching the end of Orion’s development phase having successfully tackled many of the toughest engineering challenges associated with deep space travel,” said Mike Hawes, Lockheed Martin’s Orion program manager, in a statement to Spaceflight Now. “Now, as outlined in Lockheed Martin’s response to NASA’s RFI, we’ve identified savings that will reduce the recurring production costs of Orion by 50 percent — and we aren’t stopping there. We believe the cost savings we’ve defined in our response will enable decades of affordable human space exploration.”

“Orion is the only ship built to NASA’s rigorous requirements for human deep space travel, and remains on track for Exploration Mission-1 in 2018,” Hawes said.

NASA has spent about $10 billion on the Orion program since 2006, with another $7 billion budgeted through the EM-2 launch, according to a report by the agency’s inspector general in September.

The inspector general’s report highlighted financial concerns with the Orion program, such as Lockheed Martin’s decision to dip into management reserves to cover some of the capsule’s development costs. The watchdog also expressed concern over NASA’s optimistic timeline to launch EM-2 in 2021, writing that the aggressive target date “increases the risk that Orion officials will defer certain tasks, which ultimately could delay the program’s schedule and increase costs.”

Rival aerospace contractors Boeing and SpaceX are working on their own spaceships for human travel in low Earth orbit. The companies have NASA contracts to build the CST-100 Starliner and Crew Dragon space taxis for trips to and from the International Space Station.

Those designs would need upgrades for deep space missions.

SpaceX founder and chief executive Elon Musk announced his vision for human expeditions to Mars in September at the International Astronautical Congress in Mexico. While long on technical detail and rationale, Musk’s presentation lacked a firm cost estimate or an implementation plan.

Musk and top NASA managers have been careful to avoid pitting the SpaceX vision and NASA’s government-funded Mars plans against one another. In his remarks in September, Musk said his concept for sending hundreds of people to Mars would require government funding.

“It’s not a competition between these pieces,” said Bill Gerstenmaier, associate administrator of NASA’s human exploration and operations directorate. “We’ve got to all work together to go ahead and make this happen.”

Gerstenmaier acknowledged Nov. 4 that some core components of NASA’s deep space plan may end up eventually being set aside.

“In terms of the heavy-lift launch vehicle, I don’t know if the SLS will be the vehicle forever, but it can surely fill this initial gap where we can get large masses to space, and we can enable things with that that we couldn’t do otherwise,” Gerstenmaier said at the New Worlds 2016 conference last week in Austin, Texas. “Could we carry some large infrastructure for Mars that some private sector company needs?”

NASA officials and many scientists have lauded the Space Launch System’s ability to launch robotic probes when it is not needed by astronaut crews. It could launch a flyby mission and automated lander to Jupiter’s Europa, a spacecraft to return surface samples from Mars, or dispatch speedy missions to the outer solar system much faster than existing rockets.

The SLS has powerful political backers in the Republican-controlled Congress, including Sen. Richard Shelby (R-Ala.), who chairs the Senate subcommittee responsible for writing NASA’s budget. Alabama is home to the Marshall Space Flight Center, headquarters of the SLS development team.

While NASA’s Orion RFI raises questions, it does not solicit formal proposals for an Orion alternative.

The space agency could opt to give Lockheed Martin a contract extension through a “sole source” arrangement, or an open competition among bidders could still result in a win for the big aerospace contractor.

Industry officials said the wording of the request for information released in September, which calls for responses based on the reproduction of Orion crew capsules as developed under the existing contract, could also favor Lockheed Martin, which already has the tooling and processes in place for Orion assembly and construction.

But the RFI means NASA officials want to keep their options open, just as President-elect Donald Trump prepares to nominate a new NASA administrator and policy team who could shake up the agency’s portfolio.

Robert Walker, a former Republican congressman appointed space policy advisor to the Trump campaign last month, is leading the NASA transition team with Mark Albrecht, a senior space advisor to President George H. W. Bush, former president of International Launch Services and now chairman of U.S. Space LLC.

The scant details of a Trump space policy show the new president wants NASA to focus on human spaceflight and deep space exploration, and reduce its emphasis on climate science.

“NASA should be focused primarily on deep space activities rather than Earth-centric work that is better handled by other agencies,” wrote Walker and Peter Navarro, another Trump policy advisor, in an op-ed published by Space News last month. “Human exploration of our entire solar system by the end of this century should be NASA’s focus and goal. Developing the technologies to meet that goal would severely challenge our present knowledge base, but that should be a reason for exploration and science.”

Walker and Navarro did not single out a destination for humans in space, and some observers believe the Trump administration could redirect NASA to return astronauts to the moon’s surface, a mission that could be supported with the existing SLS and Orion programs, if they remain intact.

They also expressed support for the International Space Station, but added that the partnership should be expanded to include new international and commercial partners.

“Space station activities must also remain robust given their long delayed, but now functioning, research potential,” they wrote. “However, the U.S., working with the international community, should seek new participants in its mission and look to transitioning the station to a quasi-public facility supported by international contributions and resupplied utilizing commercially available services.”

Gerstenmaier, a career civil servant whose NASA career began in 1977, lauded the financial flexibility of NASA’s approach to deep space exploration with crews, which assumes a flat top-line NASA budget.

“The problem we had before (with planning missions to deep space) is we always assumed that if we had a compelling program, the money would flow and we would get some great advance,” Gerstenmaier said. “We’d get the compelling program for a little a while, and then it fades, and then it drops. Then we go through these big swings of stop all this hardware development and start all this hardware development.

“We kind of said, ‘OK, historically, NASA’s budget has been about at the level it is right now,” he said. “It’s not going to go up by a lot and it’s not going to go down by a lot. If we just have that much money, and leveraging off of the private sector, what can we do at a slow, measured pace? That’s what we’ve laid out that gets us (to Mars orbit) in 2033.”

Gerstenmaier said NASA’s sights remain firmly on Mars, following President Barack Obama’s 2010 space policy directive that canceled the Bush-era Constellation moon program, turned over responsibility for crew transportation to low Earth orbit to the private sector after the space shuttle’s retirement, and set an asteroid and the red planet as the agency’s long-term destination.

He said the presidential transition will be the “first test” of NASA’s more methodical, budget-driven approach as it comes under the influence of a new administration.

“It’ll be interesting to see,” Gerstenmaier said. “I think we’re poised, based on our past experience, to be robust to make it through this transition, but I don’t know. I’m an experimentalist. We’ll see if we’re ready.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.