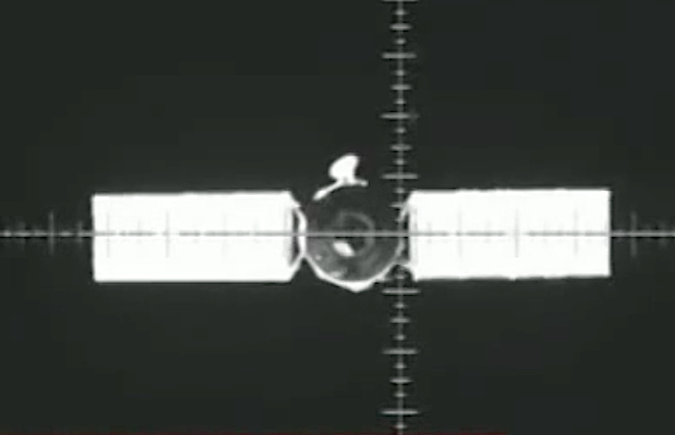

China’s Tiangong 1 space lab, replaced by an upgraded human-rated research station launched last week, is heading for an uncontrolled re-entry back into Earth’s atmosphere in late 2017.

The crash is not expected to cause any damage — only a small fraction of Tiangong 1 will survive the destructive heat of re-entry — but the Chinese mini-space station will be one of the largest objects to make an unguided descent from orbit in recent years.

The spacecraft is currently orbiting about 370 kilometers (230 miles) above Earth and losing more than 100 meters (330 feet) of altitude each day from the effects of atmospheric drag, according to Wu Ping, deputy director of China’s Manned Space Agency.

The Tiangong 1 spacecraft stopped functioning in March, four-and-a-half years after it launched Sept. 29, 2011. Wu said the mission was originally designed to last two years.

It weighed about 8.5 metric tons (18,739 pounds) when it launched with a full load of propellants, but Tiangong 1 has burned some of that fuel during its mission, which included six docking maneuvers with three spacecraft: Shenzhou 8, 9 and 10.

The first of Tiangong 1’s three visiting vehicles, Shenzhou 8, carried out unpiloted tests without a crew in November 2011. Two later flights, Shenzhou 9 and 10, each carried three Chinese astronauts for two-week flights to Tiangong 1 in June 2012 and June 2013.

Tiangong means “heavenly palace” in Chinese, while Shenzhou roughly translates as “divine vessel.”

Measuring 10.4 meters (34 feet) long and 3.4 meters (11 feet) wide, Tiangong 1 is about the size of a bus. When the space lab falls out of orbit, it will be one of the most massive known satellites to make an uncontrolled re-entry over the last two decades, surpassing the size of NASA’s Upper Atmospheric Research Satellite, which garnered wide publicity when it re-entered the atmosphere out of control in 2011.

But Tiangong 1 is a fraction of the size of previous space stations that came back to Earth unguided.

Russia’s Salyut 7 station — more than twice as massive as Tiangong 1 — re-entered the atmosphere over South America in 1991. NASA’s nearly 100-ton Skylab space station made a famous re-entry over Australia in 1979, spreading debris across the continent.

The Aerospace Corp., which studies space debris and re-entry behavior, says about 10 to 40 percent of falling satellites and rocket bodies survive the intense heat of re-entry to reach Earth’s surface.

No one has ever been injured from falling space junk, but re-entry debris has caused damage to property.

In a press conference last week, Wu said the risk from Tiangong 1 is “extremely low.”

“We estimate that it will experience its downfall by the latter half of 2017, which is next year,” Wu said. “(From) close analysis, most of its assembly units will burn and be destroyed during the downfall and will have a very low possibility of causing damage on Earth.”

The thin outer layers of Earth’s atmosphere are pulling Tiangong 1 out of orbit. Low-density air particles at Tiangong 1’s altitude impart minuscule levels of aerodynamic drag, pulling the spacecraft closer to Earth.

As Tiangong 1 loses altitude, it will encounter thicker parts of the upper atmosphere, and its descent rate will increase.

Tiangong 1’s orbit takes it around Earth every hour-and-a-half between 43 degrees north and south latitude. While it is impossible to predict the space lab’s re-entry point a year or more ahead of time, its footprint is restricted to that swath of the planet.

China launched the upgraded Tiangong 2 research module Sept. 15 to replace the defunct Tiangong 1 space lab. The new spacecraft carries several upgrades, including a robotic arm and refueling equipment, necessary to refine technologies for China’s planned multi-module space station due for completion by 2022.

Wu said China takes space debris concerns seriously, and some of the country’s launchers now conduct disposal maneuvers after deploying their payloads to guide spent upper stages toward destructive re-entries over the ocean.

Chinese engineers have also built and launched experimental satellites to demonstrate how to clean up space junk.

But China’s space debris record is marred by an anti-satellite weapons test in 2007 that intentionally shattered an aging Chinese polar-orbiting weather satellite, creating thousands of new fragments that could wreak havoc if they impact another spacecraft.

“We’ll continue to monitor closely Tiangong 1’s operation and issue early warnings for possible crashes, and report to the world in a timely manner,” Wu said.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.