NASA managers face a July 12 deadline to decide whether to send the Dawn spacecraft on an unplanned visit to a third object in the asteroid belt or keep the probe at dwarf planet Ceres until it runs out of fuel next year, officials said this week.

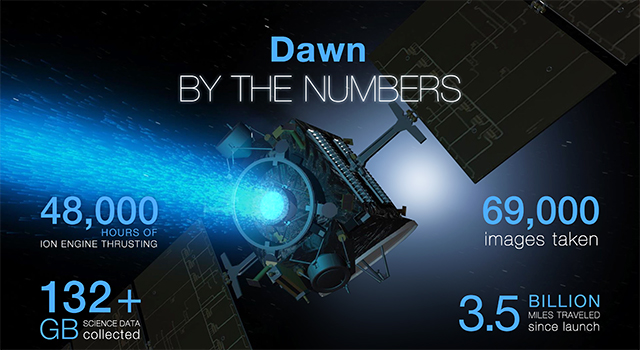

Launched in September 2007 and in orbit around Ceres since March 2015, Dawn reaches the end of its primary mission Thursday, and NASA officials must decide soon whether to release funding for extended operations.

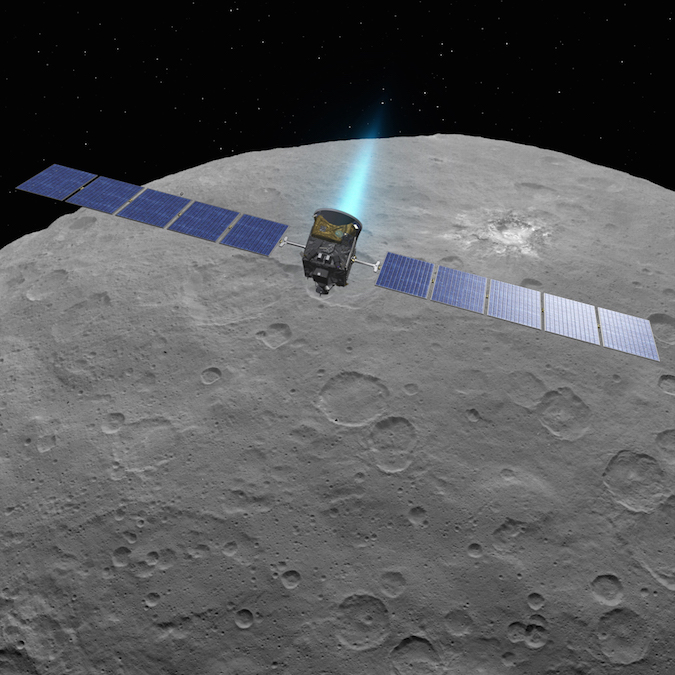

All of the space agency’s long-lived interplanetary missions come up for review every two years, but Dawn is a special case. Scientists in charge of the mission proposed dispatching the solar-powered probe toward another asteroid, but it must fire its ion engines to escape the orbit of Ceres by July 12 to make the journey possible, according to Carol Raymond, Dawn’s deputy principal investigator at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Dawn mission managers have not publicly revealed the identity of the asteroid they would like to visit. The destination will be announced if NASA Headquarters approves the plan, Raymond said.

The proposed extension would result in a slow flyby of the target asteroid, she said, and the bonus destination would keep Dawn operating through 2019. Built under contract to NASA by Orbital ATK, the probe has already made history as the first spacecraft to ever orbit two worlds beyond the Earth and the moon, taking the first close-up observations of the giant asteroid Vesta in 2011 and 2012 before flying to Ceres.

Dawn discovered bright salt deposits on Ceres, and a huge mountain on Vesta towering twice as tall as Mount Everest.

Mission managers long said Dawn did not have enough fuel to cruise to another object, but the spacecraft has performed flawlessly since it arrived in orbit around Ceres last year, burning much less hydrazine fuel than predicted.

“Even for those of us working on the team, it came as really a surprise, a very pleasant surprise, but a surprise nonetheless,” Raymond said Tuesday in a presentation to NASA’s Small Bodies Assessment Group, a meeting of scientists with expertise in asteroids, comets and dwarf planets.

Two of Dawn’s four reaction wheels, fast-spinning gyroscope-like devices that control the spacecraft’s pointing, failed earlier in the mission. Officials expected the failures would require Dawn to fire its chemical rocket thrusters more often to change and maintain the probe’s orientation.

The thrusters burn hydrazine, and Dawn has a limited supply of it on-board.

“The question is how did this happen? The answer is it’s always been the hydrazine,” Raymond said. “In 2012, following our second reaction wheel failure as we were departing from Vesta, we made an estimate that the amount of hydrazine we needed to complete the Ceres mission was twice the amount we had remaining on-board, and the team worked very hard to execute an aggressive and persistent campaign to conserve the hydrazine.

“In 2016, we ended not only achieving our intended mission, but with a surplus, which we can now use to do something else,” she said.

Scientists said Dawn completed all its primary science objectives in March, and the spacecraft’s German imaging camera, U.S.-made water-seeking neutron detector, and Italian-built mineralogy mapper spent the last four months filling in gaps.

Dawn’s two remaining reaction wheels show no sign of failing since they were activated when the spacecraft reached its current 230-mile-high (375-kilometer) orbit around Ceres, the lowest altitude in the mission’s flight plan. The pointing wheels could still run into trouble at any time, but their smooth operation has kept hydrazine usage to a minimum.

“This has resulted in an excess of about eight kilograms (17 pounds) of hydrazine,” Raymond said.

Dawn needed the reaction wheels at lower altitudes to fight against torque from Ceres’ weak gravity field that could pull the spacecraft off its proper orientation. Without the wheels, engineers figured Dawn would quickly burn through its leftover hydrazine fuel.

“They have worked, and it’s given us more than five kilograms (11 pounds) of savings in the hydrazine, and along with the fact that we didn’t have anomalies … we banked that extra hydrazine as well,” Raymond said.

“In the words of of Bugs Bunny, Dawn at Ceres has been a wheel success,” she joked.

But Dawn’s next move depends on a decision due from NASA Headquarters in the coming days.

“We are awaiting a response any day now, I hope, because we’re on a very tight timeline to leave Ceres by July 12 in order not to expend more hydrazine at Ceres because, at some point, we’ll rapidly run out of the ability to leave Ceres and go anywhere else,” Raymond said.

Jim Green, head of NASA’s planetary science division at NASA Headquarters, said Wednesday that agency officials will decide the fate of Dawn this week or next week.

“We are very sensitive to that,” Green said of the July 12 deadline. “That hasn’t lost our attention.”

Dawn is one of nine planetary science missions, including the New Horizons probe that flew past Pluto in July 2015, up for extensions this year. Other projects awaiting a decision from NASA leadership include the Curiosity and Opportunity Mars rovers, the Mars Odyssey and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter missions, and the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

New Horizons is aiming for a flyby of a distant Kuiper Belt Object beyond Pluto on Jan. 1, 2019. The probe has already steered on to a path toward its new target, but like Dawn, its future hangs in the balance of NASA’s looming decision.

The space agency convened a board of senior planetary scientists to review mission extension proposals submitted by each project’s science team, and Green said the panel has delivered its recommendations to NASA, which must match the independent review results with budget constraints.

If NASA does not approve the Dawn team’s plan to redirect the spacecraft to another asteroid, the craft could remain in orbit around Ceres through March or April 2017, assuming its reaction wheels remain healthy, Raymond said.

If Dawn lost another reaction wheel tomorrow, she said the probe would likely run out of fuel by September.

“Should we not leave Ceres, that’s not to say that’s a loss for this community or for the project because Ceres is a fascinating place, and obviously there will be more data collected,” Raymond said. “But I’d also like to make the case that I think we’ve gotten so much already that the incremental amount of knowledge that we would gain would be maybe not as great as one would have thought.”

One standout feature found on Ceres is a salt dome inside Occator Crater, an 80 million-year old impact scar measuring 57 miles (82 kilometers) wide. In a paper published online this week by Nature, scientists contend the salt deposits in Occator are primarily made of sodium carbonate, a mineral found on Earth in hydrothermal environments.

Researchers previously thought the bright areas were composed mostly of magnesium sulfate, a different kind of salt.

“The minerals we have found at the Occator central bright area require alteration by water,” said Maria Cristina De Sanctis, lead author of the paper and principal investigator on Dawn’s visible and infrared mapping spectrometer from the National Institute Astrophysics in Rome. “Carbonates support the idea that Ceres had interior hydrothermal activity, which pushed these materials to the surface within Occator.”

The results suggest that the salts could be the remnants of a liquid ocean or localized bodies of water that froze millions of years ago, relatively recently on geologic time scales, scientists said.

“We are now getting an idea of what the interior looks like, and what Ceres’ history may have been like in terms of its differentiation, but we’re still grappling with the question of is it active today?” Raymond said.

In any case, Dawn has left scientists with a treasure trove of data on Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt. Now Dawn is ready to move on, Raymond said.

Mission controllers at JPL have already pre-planned the commands for Dawn to start up its xenon-fueled ion thrusters in the coming weeks. Those orders could be transmitted to the spacecraft once NASA delivers a ruling.

“We are right on the edge,” Raymond said. “It is kind of a drop-dead date, July 12, for leaving.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.