NOAA’s Deep Space Climate Observatory, a $340 million mission that spent more than a decade grounded in a Maryland warehouse, will begin warning forecasters of dangerous solar storms next month, giving notice of events that could disrupt air travel, radio communications, electrical grids and satellite operations.

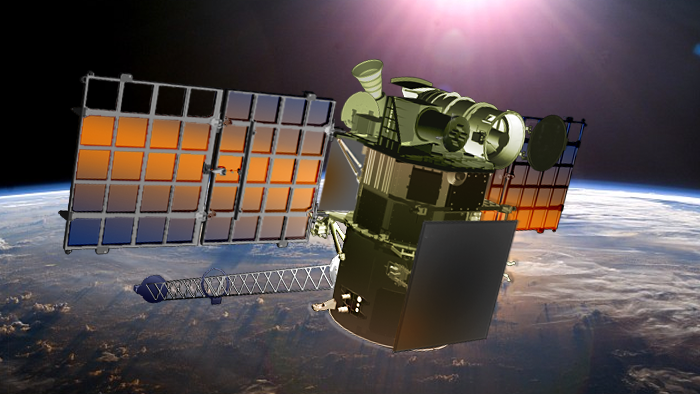

Positioned in a halo-like orbit around the L1 Lagrange point nearly a million miles (about 1.5 million kilometers) from Earth in line with the sun, the DSCOVR spacecraft is beginning a mission of at least two years monitoring the solar wind, looking for spikes that could spark powerful geomagnetic storms at Earth.

“Even though the sun is 93 million miles away, activity on the surface of the sun can have significant impacts here on Earth,” said Tom Berger, director of NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center. “Severe space weather can disrupt power grids, marine and aviation navigation, satellite operations, GPS systems and communication technologies.”

Launched from Cape Canaveral aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket in February 2015, DSCOVR is a joint project between mission leader NOAA, NASA and the U.S. Air Force. The spacecraft cruised to the L1 Lagrange point, arriving last June to begin a comprehensive engineering checkout before managers pressed the observatory into service.

NOAA announced last week that DSCOVR has completed instrument validations and will go operational July 27.

“DSCOVR will allow us to deliver more timely, accurate, and actionable geomagnetic storm warnings, giving people time to prevent damage and disruption of important technological systems,” Berger said.

The early warning platform carries a Faraday Cup plasma sensor to measure the speed, density and temperature of the solar wind, and a magnetometer to measure the strength and direction of the solar magnetic field, according to NOAA.

DSCOVR also hosts two NASA-managed instruments: a camera to acquire full-disk images of the day side of Earth and a radiometer to monitor the planet’s energy budget. The imager returns spectacular snapshots of Earth several times per day, and the radiometer provides data for climate change researchers.

But the chief purpose of DSCOVR is space weather forecasting, and NOAA says information collected by the satellite will help experts predict geomagnetic storms on regional scales, an improvement over the global forecasts currently issued.

“DSCOVR data will be used in a new forecast model – the Geospace Model – due to come on line this year,” NOAA said in a statement. “The Geospace Model will enable forecasters to issue regional, short-term space weather forecasts for the first time, including predictions on the timing and strength of a solar storm that will impact Earth.”

The spacecraft’s location at L1 gives space weather forecasters, satellite operators, and infrastructure managers up to an hour of warning before the effects of a solar storm arrive at Earth.

Data from DSCOVR will be distributed to the public, along with official forecasts from NOAA.

The new observatory replaces NASA’s aging Advanced Composition Explorer, which launched in 1997 and is operating well beyond its design life. DSCOVR is slated to function at least two years, but it carries enough fuel for at least five years of operations.

ACE will be kept in a backup role until at least next year, when NASA will decide on the future of the mission.

NOAA plans to have an upgraded replacement for DSCOVR ready for launch in 2022, according to the agency’s budget documents.

“There is a plan for space weather continuity after DSCOVR,” said Doug Biesecker, DSCOVR mission scientist at NOAA. “The baseline mission is to provide in-situ magnetic field, thermal plasma, supra-thermal ions, and a remote-sensing instrument, a coronagraph.”

The coronagraph instrument is not aboard DSCOVR, and it would replace the remote imaging capability currently offered by the NASA/ESA SOHO mission at L1. A coronagraph provides scientists warning of approaching solar storms as they are triggered by massive eruptions on the sun, several days before the effects arrive on Earth.

NOAA’s budget request for fiscal year 2017 asks for money for two spacecraft, two launch vehicles and two sets of instruments, and the program has won initial support from lawmakers drafting the agency’s final budget. The first of the satellites would be launched in 2022 at the end of DSCOVR’s projected life.

The DSCOVR mission had to wait nearly two decades since its inception after the project became tied up in political wrangling in Washington.

First proposed by then-Vice President Al Gore in 1998, the mission was supposed to broadcast live views of Earth from a distant vista a million miles away for live streaming on the Internet. Gore believed the mission — which Gore named Triana after one of the sailors on Columbus’s 1492 voyage to the new world — would raise awareness of environmental issues, and scientists developed instruments to collect data on the planet’s climate.

But Republican lawmakers decried the mission as Gore’s pet project, and Congress ordered NASA to stop work on Triana in late 1999. The space agency transferred the nearly-complete satellite into storage in November 2001 after President George W. Bush took office.

NASA formally canceled the mission in 2005 after renaming Triana as DSCOVR. The space agency said the spacecraft, which was originally designed to launch on the space shuttle, could not fit on one of the shuttle’s remaining missions.

NOAA took charge of the mission in 2008 to replace ACE, and the U.S. Air Force signed on to pay for DSCOVR’s launch on a Falcon 9 rocket.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.