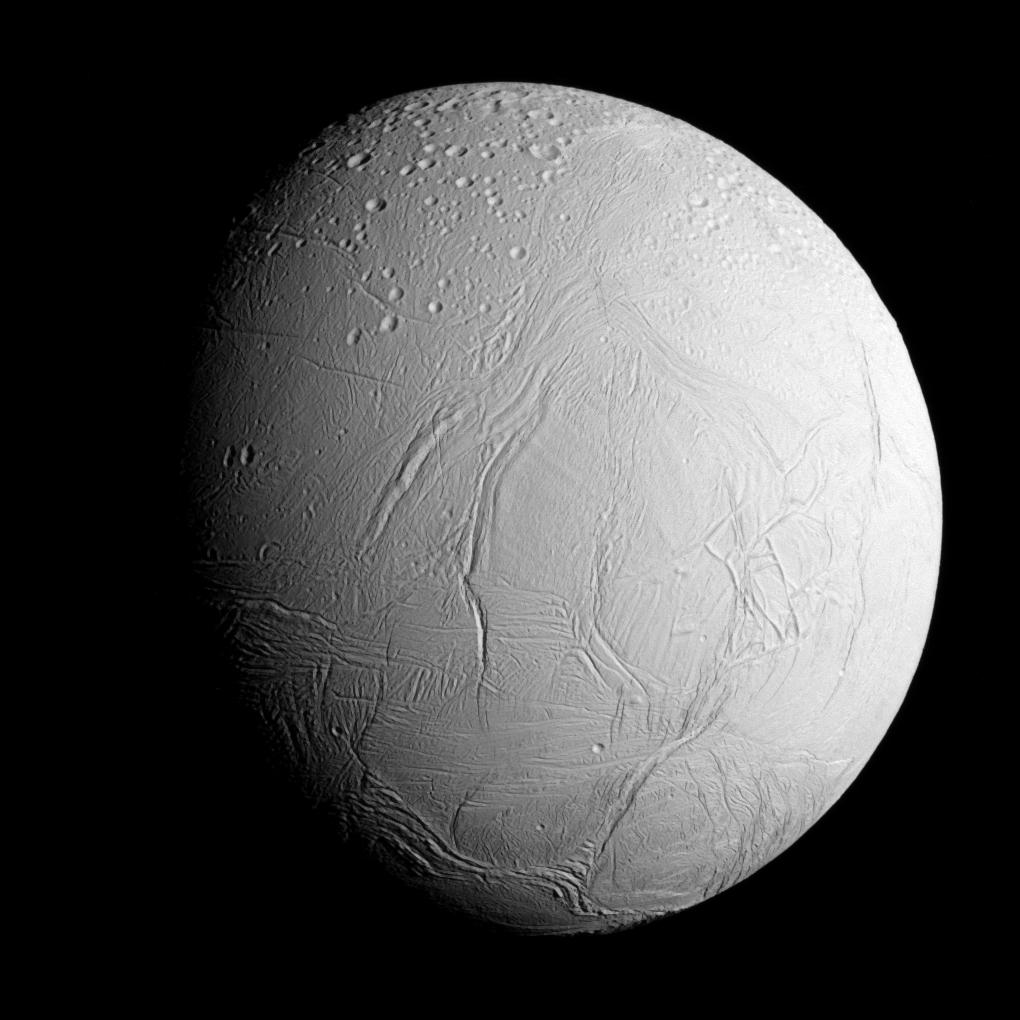

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

Days after a fleeting plunge through the icy plumes of Saturn’s moon Enceladus, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft is broadcasting tantalizing data back to Earth for scientists eager to address the moon’s prospects for life.

Cassini is not equipped to detect microorganisms that could be lurking in a global ocean buried beneath Enceladus’ frozen crust, but the probe’s instrumentation could shed light on whether the subsurface sea has the right conditions for life.

In the final stages of its more than decade-long mission at Saturn, Cassini zipped through a wall of haze flowing away from the moon’s south pole Wednesday. The flyby was Cassini’s 21st — and penultimate — time to approach Enceladus, but Wednesday’s encounter was the spacecraft’s deepest dive into the plumes, which Cassini discovered in 2005.

With Cassini’s less than two years from ending its mission, Wednesday’s flyby was the last chance to sample Enceladus’ plumes, likely for decades. Although scientists are working on concepts for a follow-up probe to further explore the moon, NASA has not approved a mission.

Spaceflight Now members can read a transcript of our full interview with Jonathan Lunine. Become a member today and support our coverage.

“I think we’ll get superb data, and I’m looking forward to discovering some new molecules in the plume, and some new things about the icy grains that are there,” said Jonathan Lunine, a member of Cassini’s science team at Cornell University. “It’s going to be really high quality data, better than we’ve gotten before.

“But we also know that this is going to create a new set of questions, as any good data set does,” said Lunine, who specializes in the outer solar system’s icy bodies and has a research interest in the search for life. “We’re not going to be able to go back with Cassini and say we’re going to do another plume passage to address those questions, so that’s a little tough.”

Zipping just 30 miles from the surface, Cassini sped past Enceladus at 19,000 mph, with its sensors primed to measure the composition of gas and ice particles launched from the underground ocean. Cassini’s cameras also trained on the moon, collecting the closest ever views of Enceladus’ chaotic crust, capturing views scientists hoped would help reveal whether the geyser-like eruptions come from long fissures or from a number of discrete vents.

NASA released the first images from the flyby Friday, showing distinguishable “tiger stripes” coursing across the moon’s southern hemisphere, features believed to be related to the eruptions. Ground teams used computer processing to clean up smear caused by Cassini’s lightning fast flyby, producing close-up view of Enceladus taken just 77 miles (124 kilometers) above its surface.

“Cassini’s stunning images are providing us a quick look at Enceladus from this ultra-close flyby, but some of the most exciting science is yet to come,” said Linda Spilker, the mission’s project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

Scientists are looking for a detection of molecular hydrogen in the plumes, a measurement that would help verify suspected hydrothermal activity at the floor of Enceladus’ ocean, a discovery experts say could fuel alien microbes. But a negative detection of hydrogen would not rule out hydrothermal activity, according to Lunine.

“Hydrogen is very reactive, and if it’s made at the base of the ocean — if indeed it is made there — it’s quite possible that it reacts with some other molecules or possibly even gets eaten up by life if life is present,” Lunine said in an interview with Spaceflight Now before Wednesday’s flyby. “Even in the case of the Earth, one often doesn’t measure as much hydrogen at these tantalizing hydrothermal systems as one would expect. So we’ll look for it.”

Cassini was also primed to look for more complex carbon-bearing organic molecules embedded in the plumes.

A final flyby of Enceladus is set for Dec. 19, but Cassini’s trajectory will take it farther from the moon during that encounter.

Cassini will make a final series of flybys of Saturn’s largest moon Titan next year, then shift its ever-changing orbit to pass between Saturn and its huge ring system for the first time, gaining unprecedented observations close to Saturn’s pale yellow atmosphere.

Running low on fuel after nearly 20 years in space, Cassini will dive into Saturn in September 2017 to end the mission.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.

Saturn: Exploring the Ringed Planet

Find out more about Enceladus in this 196-page special edition from Astronomy Now. Order online.