Scientists are getting a final look at Saturn’s icy moon Dione for decades to come with fresh imagery streaming down this week from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, which made its last close flyby of the Texas-sized satellite Monday.

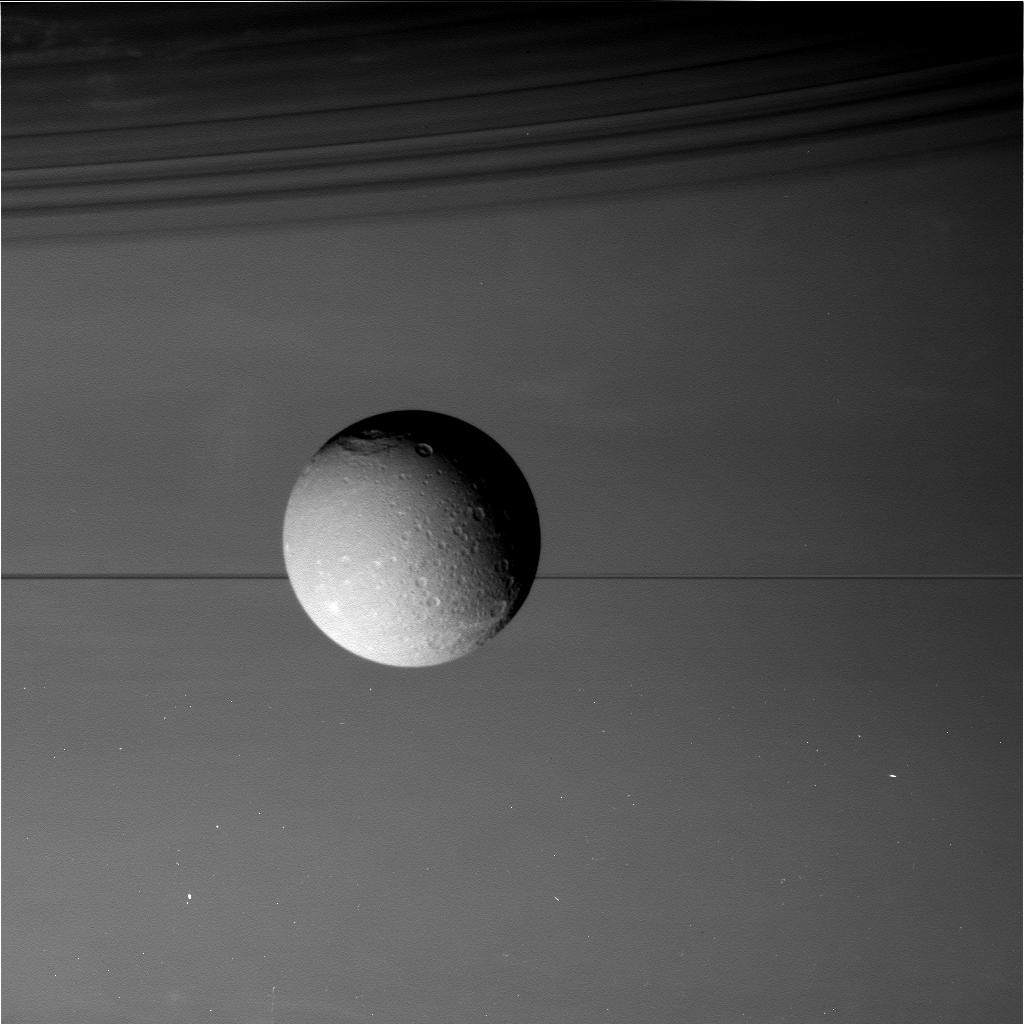

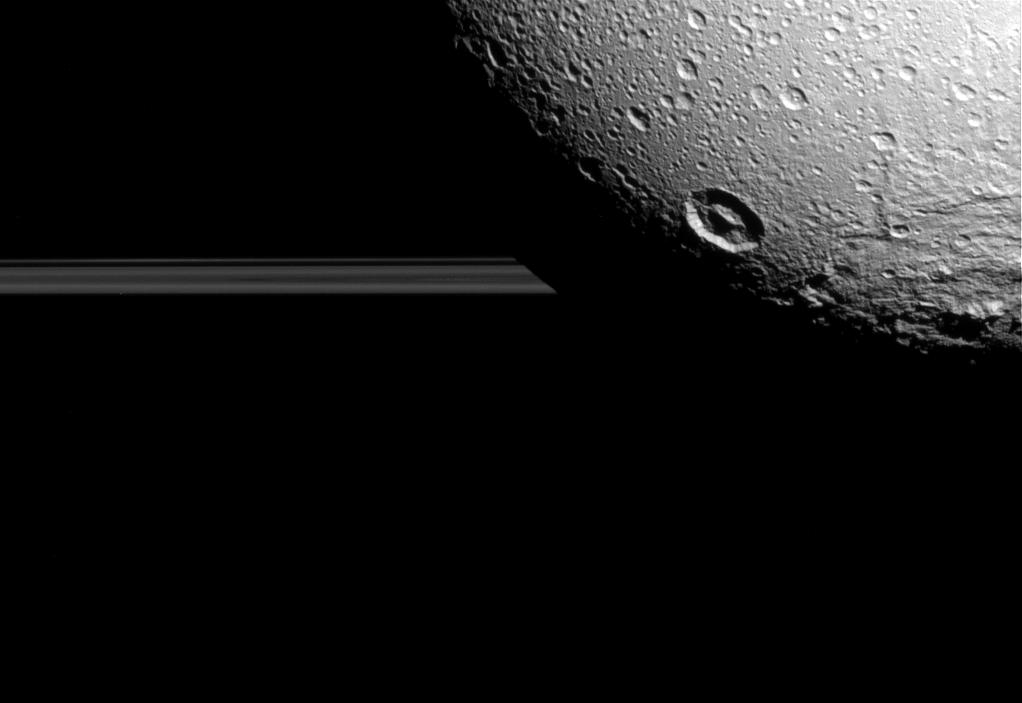

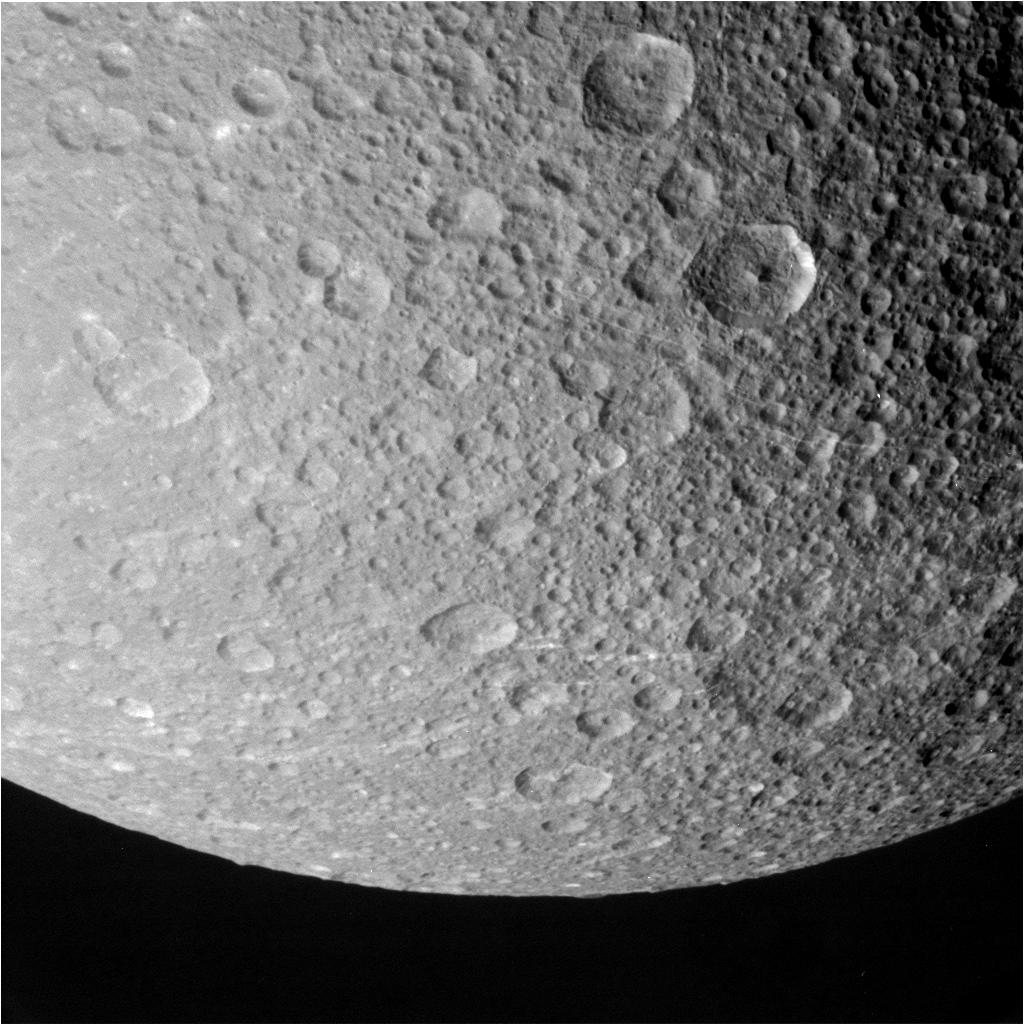

The raw images from Cassini’s camera show Dione projected against a dramatic backdrop of Saturn’s hazy atmosphere and famous rings and close-up views of Dione’s frozen, cratered surface.

Cassini targeted a trajectory passing about 295 miles — 474 kilometers — from Dione. The prime science objectives of the flyby included image-taking, gathering gravity science data to study Dione’s internal structure, mapping regions on the moon thought to be thermal traps, and searching for dust particles emitted from Dione.

High-resolution photos of Dione’s north pole were also expected.

Dione measures about 698 miles — 1,123 kilometers — in diameter and completes one lap around Saturn every 2.7 day. It circles the gas giant at about the same distance as the moon orbits Earth.

Researchers hope data from the flyby, which is still being transmitted from Cassini, will help determine whether Dione is geologically active like some of Saturn’s other moons.

Cassini’s four previous nearby encounters with Dione revealed brilliant wispy streaks across its surface. Sharp imagery showed the features to be part of a canyon system with towering walls covered in bright ice.

“Dione has been an enigma, giving hints of active geologic processes, including a transient atmosphere and evidence of ice volcanoes. But we’ve never found the smoking gun. The fifth flyby of Dione (was) our last chance,” said Bonnie Buratti, a Cassini science team member at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

In its 12th year orbiting Saturn, Cassini is busily ticking off a series of “lasts” on its to-do list as the spacecraft heads for a destructive dive into Saturn in September 2017. The probe is running low on propellant, so scientists devised a plan to guide Cassini into an uncharted region inside of Saturn’s rings before the end of the mission.

But the flight plan means Cassini will no longer pass through Saturn’s extensive moon system.

Cassini’s last flyby of Hyperion, a moon with a striking sponge-like appearance, occurred in May. After Monday’s final encounter with Dione, Cassini heads for a series of three flybys of Enceladus, which has geysers erupting near its south pole spitting out material from an underground ocean.

One of the flybys scheduled for Oct. 28 will place Cassini just 30 miles over Enceladus and is timed for when the moon’s plumes are at maximum output. The mission’s last close visit to Enceladus is set for Dec. 19.

Regular flybys of Titan, Saturn’s largest moon with a thick nitrogen-methane atmosphere, will continue through late 2016.

“This will be our last chance to see Dione up close for many years to come,” said Scott Edgington, Cassini mission deputy project scientist at JPL, before Monday’s flyby. “Cassini has provided insights into this icy moon’s mysteries, along with a rich data set and a host of new questions for scientists to ponder.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.