Images obtained during the New Horizons spacecraft’s July 14 encounter with Pluto show apparent glacial ice flows wrapping around barrier islands and towering mountain ranges, all under a newly-discovered haze layer suspended up to 100 miles above the distant world’s frozen surface, scientists said Friday.

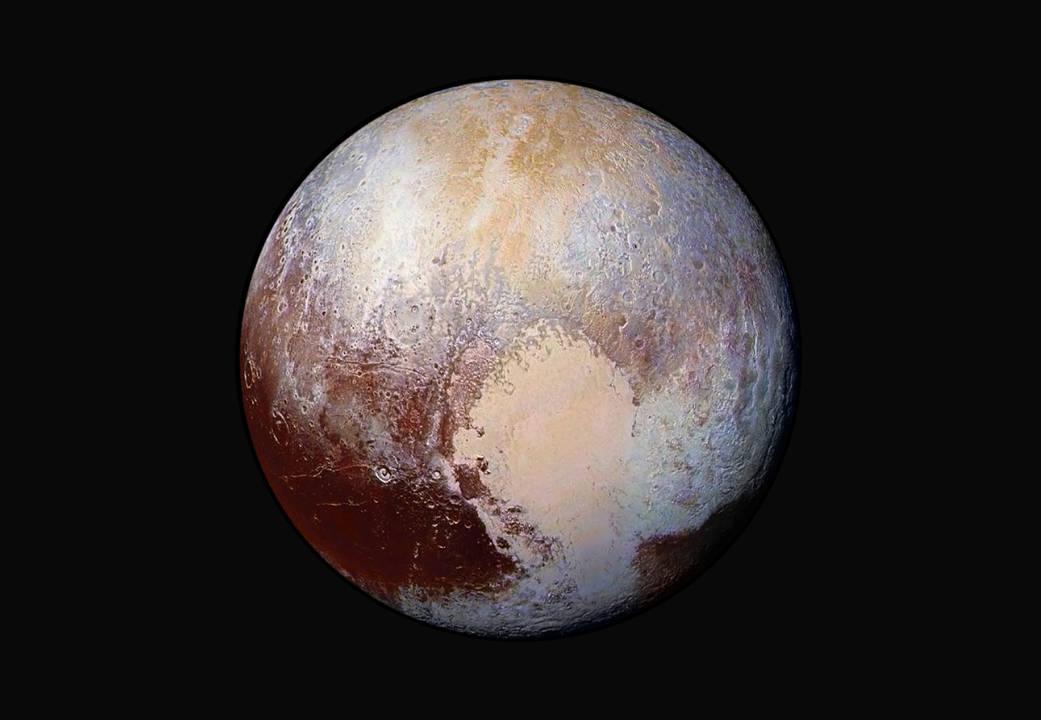

The latest views of an icy heart-shaped feature on Pluto, informally dubbed Tombaugh Regio after the dwarf planet’s discoverer, reveal complicated boundaries between relatively flat ice fields and rugged mountains primarily composed of water ice, which at Pluto’s frigid temperatures has the consistency of rock on Earth.

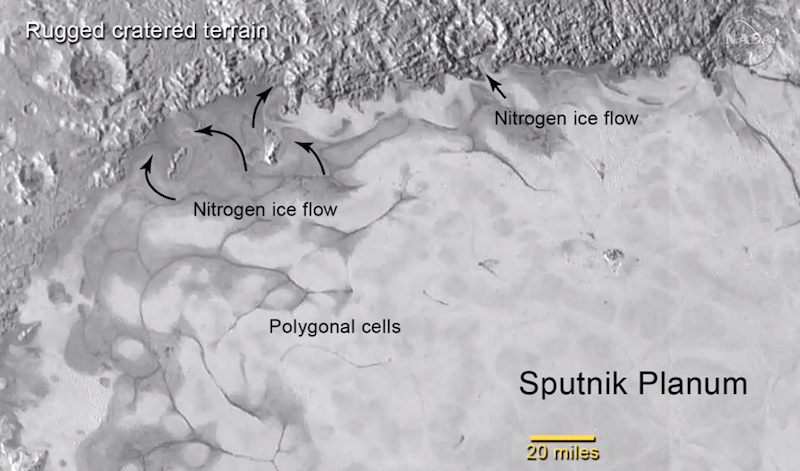

At the northern fringe of the frozen icy plain, which has been tentatively named Sputnik Planum, fingers of ice jut into mountainous topography like the fjords of Norway.

“We interpret them to be just like glacial flow on the Earth,” said William McKinnon, co-investigator on the New Horizons mission from Washington University in St. Louis. “I don’t have to remind you that glaciers on Earth are made of ice, like in Antarctica or in Greenland, but water ice at Pluto’s temperatures won’t move anywhere. It’s immobile and brittle.”

Temperature at the surface of Sputnik Planum hover around 38 Kelvin, or about minus 390 degrees Fahrenheit, according to Michael Summers, New Horizons co-investigator from George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia.

“But on Pluto, the kind of ices we think make up the (Sputnik) Planum — nitrogen ice, carbon monoxide ice, methane ice — these ices are geologically soft and malleable, even at Pluto conditions, and they will flow in the same way that glaciers do on the Earth. So we have actual evidence for basically recent geological activity.”

That is a surprise to many planetary geologists, who figured Pluto might be geologically dead with an icy surface frozen in place for billions of years.

But the smoothness of Sputnik Planum tells another story.

Researchers use crater counts to get rough estimates for the age of a geologic unit.

“When I say recent (geologic activity), I don’t necessarily mean yesterday,” McKinnon said. “I mean geologically recent. But the appearance of this terrain, the utter lack of impact craters on the Sputnik Planum, tells us that this is really a young unit.”

While Sputnik Planum may still be resurfacing today, McKinnon put an upper bound on the age of the geologic unit at a few tens of millions of years, a blink of the eye compared to the four-and-a-half billion-year age of the solar system.

Exactly what drives the geologic activity refreshing Pluto’s surface is still unclear, but McKinnon said the leading theory is remnant heat deep inside Pluto could generate slow, bubbling convection to produce the ice blocks and flows observed in Sputnik Planum.

Maybe the cataclysmic collision between Pluto and another massive object thought to produce the Texas-sized moon Charon may have occurred more recently than originally suspected, leaving Pluto’s deep interior still rumbling, some scientists believe.

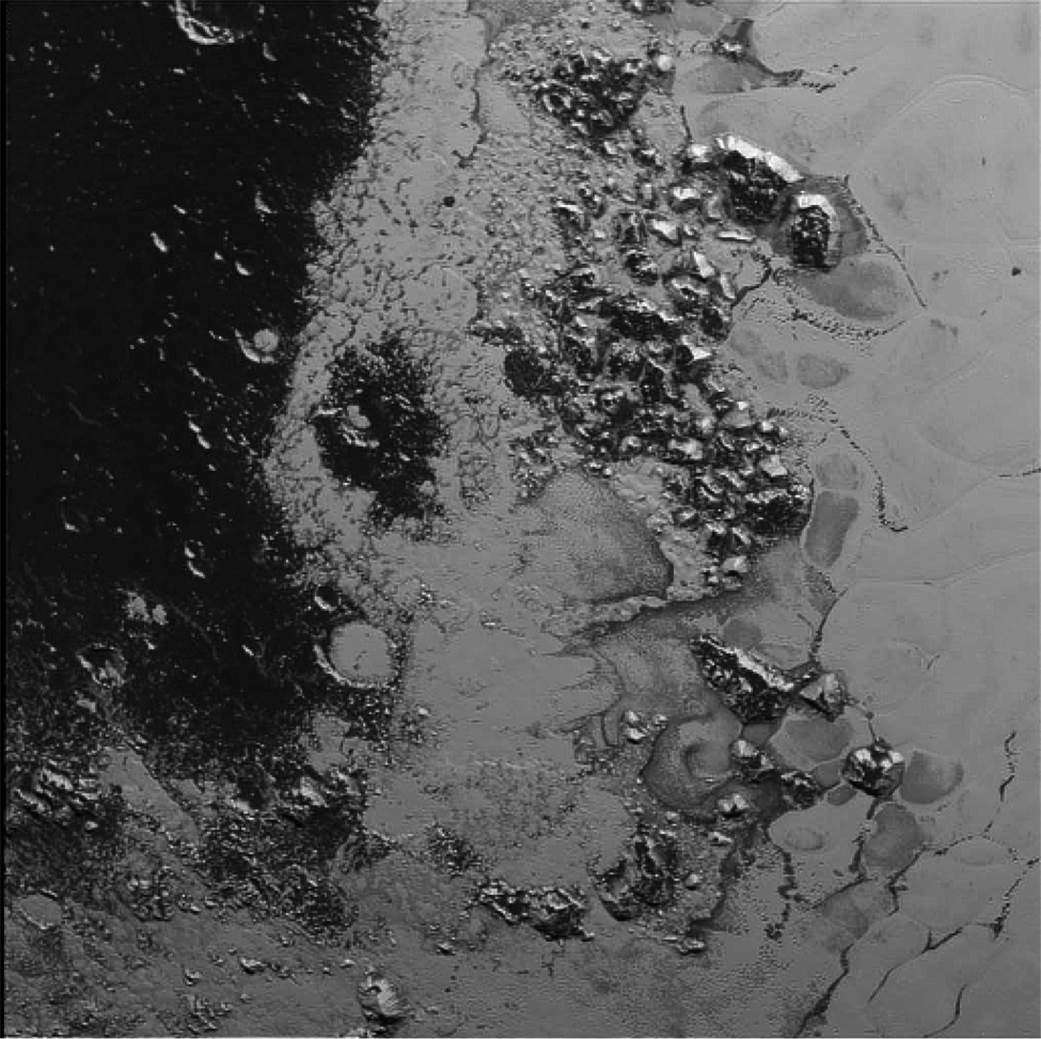

New Horizons discovered a pair of mountain ranges closer to Pluto’s equator, near the southern flank of Sputnik Planum. The ranges are unofficially named Norgay Montes and Hillary Montes after the first two people known to reach the summit of Mount Everest.

The first close-up of Pluto from New Horizons’ long-range telescopic camera revealed Norgay Montes, which rise more than 2 miles over their surrounding terrain. Hillary Montes came into focus in another image released earlier this week.

“The scientifically interesting and fascinating thing about this picture to me is that the Sputnik Planum ice — these mobile ices — seem to have moved, surrounded and embayed the Hillary Montes,” McKinnon said.

The blocks of ice in Sputnik Planum get smaller south of Hillary Montes, indicating a much thinner layer of ice there, according to McKinnon.

Beyond Hillary Montes, the ice tapers into Cthulhu Regio, part of a much darker band of surface material stretching around Pluto’s equator. The area’s asphalt-colored crust is marked by craters, leading geologists to believe it is relatively ancient.

Scientists are trying to sort out the heart-shaped Tombaugh Regio’s role in Pluto’s climate cycle. The western and eastern halves of the heart have different spectral signatures and are likely made of slightly different material, said Cathy Olkin, deputy project scientist on the New Horizons mission from the Southwest Research Institute.

Alan Stern, the New Horizons mission’s principal investigator, said the western lobe of the Tombaugh Regio heart appears to be the source for a thin layer covering the region’s eastern part.

“Bright material, probably nitrogen snow, is being transported off the source region off the western lobe, perhaps by winds and aeolian transport, perhaps by sublimation and winds and then re-condensation, or perhaps by a process we haven’t thought about,” Stern said.

Pluto takes 248 years to orbit the sun, and seasons last for many decades. The icy world’s northern hemisphere, which New Horizons flew past, is currently in basking in sunny summertime.

Before New Horizons visited Pluto, researchers knew Pluto was rich in nitrogen, methane and carbon monoxide ices that likely sublimated — turned directly from a solid to a gaseous phase — under solar heating and rained back down as tiny snow particles.

“We’re seeing methane, nitrogen and carbon monoxide ices there,” Olkin said. “This is telling us something that we need to understand. On the northern part of Pluto, we see methane and nitrogen, but not carbon monoxide, so maybe what we’re seeing in Tombaugh Regio is a source region for some of these specific ices. That complicates the story of this seasonal transport.”

Measurements show Tombaugh Regio is richer in carbon monoxide than any other part of Pluto.

“We have a vast region that seems to be truly a reservoir,” McKinnon said. “We describe this poetically as the beating heart of Pluto. It may be the supply zone, the supply hut, of the entire atmosphere.”

One thing scientists are eager to find, if it is there, is evidence of a deep underground ocean.

“We don’t have any direct evidence for an interior liquid water ocean from these images,” McKinnon said.

But based on Pluto’s low density and surface appearance, there is a good chance an ocean of liquid nitrogen, or another mixture, lurks below the world’s icy shell.

“All other things being equal, it increases the probability that there may still be an ocean way down underneath a very thick layer of ice,” McKinnon said. “That’s a theoretical inference right now, but it’s something that we’re keeping in mind as we explore Pluto.”

Only a handful of images from the July 14 Pluto flyby have reached Earth. Hundreds more are due to come down beginning in September and stretching into 2016.

But one photo recorded just after the encounter has resolved Pluto’s atmospheric haze for the first time, revealing layers of particles reaching up to 100 miles above its surface illuminated by sunlight, five times higher than models predicted.

“This is the image that stunned the encounter team,” said Summers, an atmospheric scientist on the New Horizons mission. “For 25 years, we’ve known that Pluto has an atmosphere, but it’s been known by numbers. This is the first picture, this is the first time we’ve really seen it. This was the image that almost brought tears to the eyes to the atmospheric scientists on the team.”

Now scientists are trying couple the geologic and atmospheric data to unravel how the Pluto system works.

“The haze is pretty,” Summers said. “It’s a way to see the atmosphere, but it’s a piece of a big story that we’re trying to understand at Pluto, and that is how the atmosphere and the surfaces are connected.”

Methane particles lofted from Pluto’s surface are irradiated high up in Pluto’s atmosphere, creating ethylene, acetylene and other varieties of particles named tholins detected by New Horizons.

The particles then fall back to Pluto to create the icy dwarf’s red veneer.

“At some point in this cycle, those haze particles are chemically processed to produce what we call tholins, which are chemically altered hydrocarbons that have a red color,” Summers said. “We think that is how Pluto’s surface got its reddish hue.”

“On Pluto, we have a much more intimate and intricate interaction between geology, volatile transport and the seasonal climate cycles — those kinds of things — that are foricng one another, and feeding one another, and creating a very complicated and layered story about the planet’s history,” Stern said. “It’s rare in the pantheon of objects in the solar system that we have seen this kind of an intricate and complicated story. I’m reminded in some ways of (Saturn’s moon) Titan, but few other examples that are so dramatic. It’s brand new.”

New Horizons also spotted a dark, reddish deposit on Charon’s north pole, potentially created by similar tholins from Pluto’s atmosphere ending up there.

Charon does not appear to have its own atmosphere, according to new results from New Horizons’ Alice spectrometer. If it does, it is much thinner than Pluto’s.

“For now, all we can say is it’s a much more rarefied atmosphere and that confirms our pre-flight notions, and we’re really looking forward to seeing just how rarefied that is,” Stern said. “It may be that there is a thin nitrogen layer in the atmosphere, or methane, or some other constituent, but it must be very tenuous compared to Pluto, again, emphasizing just how different these two objects are despite their close association in space.”

Another science shocker from New Horizons came from the first direct measurement of Pluto’s surface pressure.

It turns out the Pluto’s atmosphere has a surface pressure of no more than 10 microbars, about one hundred thousandth the thickness of Earth’s at sea level. That’s substantially less than a measurement made from Earth two years ago, Summers said.

“The mass of Pluto’s atmosphere has decreased by factor of two in about two years,” Summers said. “That’s pretty astonishing, at least to an atmospheric scientist. That tells us something is happening.”

Using radio signals beamed up from Earth to a receiver aboard New Horizons, scientists measured Pluto’s surface pressure by studying how the signals traveled through its atmosphere. The radio science experiment, or REX, relied on high-power signals broadcast by NASA’s Deep Space Network.

New Horizons may have caught the early stages of a hypothesized collapse and freezing of Pluto’s atmosphere as it opens its distance from the sun. Pluto’s egg-shaped orbit brought the faraway world closest to the sun in 1989, and it is now about 3 billion miles away.

But Pluto’s atmospheric pressure continued rising after 1989, perhaps due to a climate lag, similar to how the hottest part of summer comes weeks after the summer equinox.

“After we saw pressure rising from occulation data, some thought maybe there’s not going to be a Pluto atmospheric collapse,” Stern said. “What REX seems to have detected is the potential for the first stages of that collapse, just as New Horizons arrived. It would be an amazing coincidence, but there are some on our team who would say ‘I told you so.'”

Less than 5 percent of the mission’s total data haul had reached the ground as of Friday, according to Stern.

“We’ve now finished the first phase of downlink,” Stern said. “That was an intensive 10-day period in which we sent down images, spectra and other datasets just to whet our appetites and tell us the basics about the Pluto system.”

More pieces of the Pluto puzzle will come down in future data downlinks, which will focus on plasma and dust measurements over the next couple of months. In September, scientists say a wider pipeline of images will come back to Earth.

“For the next couple of months, until we reach mid-September, it’ll only be occasionally that we have new images on the ground and available to release,” Stern said. “Starting in September, the spigot opens again, and then for about a year — maybe a little bit more — the sky will be raining presents with data from the Pluto system. It’s going to be quite a ride.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.