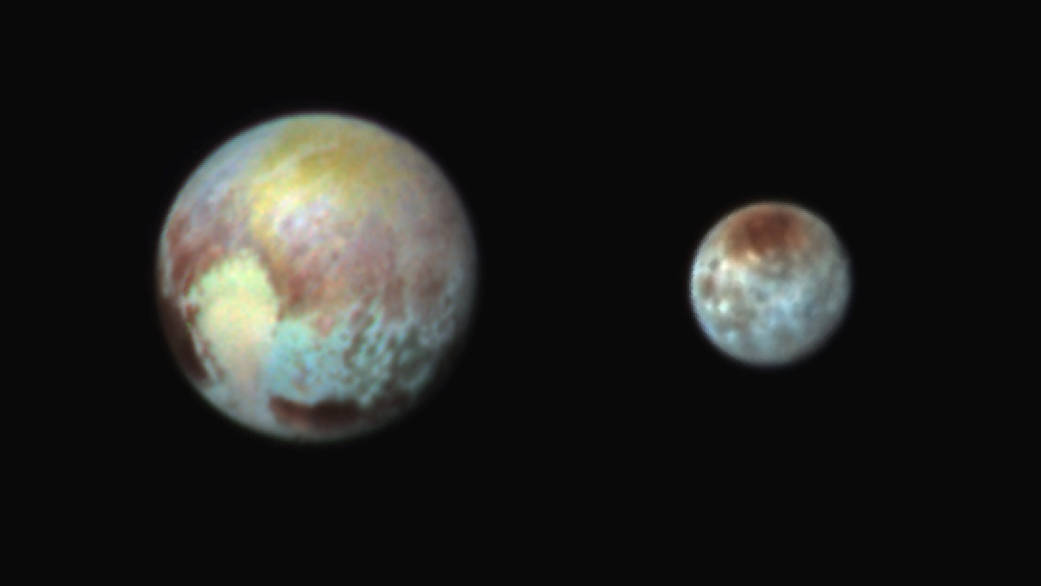

Pluto and its Texas-sized moon Charon share an alien environment on the solar system’s outer frontier, with patches of organic ices and diverse rock types illustrated in color imagery released Tuesday.

Speaking hours after NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft zoomed 7,700 miles from Pluto on the first-ever encounter with the mystery world, scientists said early images show remarkable diversity across Pluto’s surface.

The images yield new insights on the distant dwarf’s composition, a teaser before more refined data on Pluto’s mineral makeup arrives back on Earth later this week.

“From the ground, we knew that there were a lot different colors on Pluto, but we never imagined anything like this,” said Cathy Olkin, New Horizons’ deputy project scientist from the Southwest Research Institute.

Olkin said Pluto appeared “psychedelic” in color.

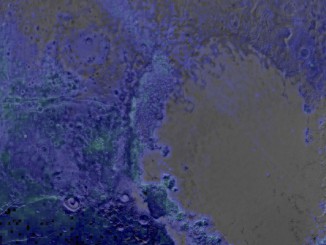

While Pluto’s appearance in recent New Horizons photos approximates what the human eye would see, the false color image exaggerates different shades of Pluto’s rust-colored crust, allowing scientists to dig deeper into the geology of the faraway outpost.

The Ralph instrument on NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft captured the color data as the probe flew inbound toward Pluto on Monday.

“This is an aesthetic moment as much as it is a science moment,” said Jeff Moore, geology and geophysics team lead at NASA’s Ames Research Center. “Having been a reader of science fiction and an admirer of space art, I don’t believe that even the best space artist in the world could make a painting as beautiful as this. This is nature outdoing us.”

The color imagery shows a brilliant heart-shaped marking appears to be divided into two compositional sections with a clear line separating the units.

“The heart actually is two different beasts,” Moore said. “The west half of the heart, which is on the left-hand side, is smooth. We think it might actually be smooth, although we can’t be completely sure.”

The images from New Horizons beamed back to Earth late Monday came down as compressed files, so scientists are not sure what features might actually be image artifacts.

“Hopefully, the pictures we’ll get back tomorrow will show whether there is, in fact, topography and texture in this region or not,” Moore said.

One thing the color imagery seems to rule out is a uniform veneer of soil and dust over large swaths of Pluto’s surface. Instead, scientists see discrete geologic units.

The false color data “show it’s not just a general layer of dirt over everything,” said John Spencer, a New Horizons co-investigator from the Southwest Research Institute. “There’s an enormous variety in the kinds of colors of the terrain, and they do seem to correlate with the geology.”

Some areas of Pluto are devoid of craters, and Moore said some craters appear to be cut in half, evidence ancient impact sites have been altered or eroded through some kind of geologic process.

“We think at least some regions on Pluto are relatively ancient,” Moore said. “They’re probably several billion years old. Other places where we see no craters at all are very young and perhaps are still currently undergoing geological evolution.

“Some process either sweeps it clean or makes new stuff,” Moore said.

Pluto’s equator, seen at the bottom of New Horizons’ images, is home to a belt of dark markings. On the face of Pluto seen during Tuesday’s flyby, Pluto’s heart feature crosses over the dark band, but geologists are not sure how to interpret the region’s appearance.

“We think the dark material is cooked up in Pluto’s atmosphere and deposited,” Spencer said. “We don’t know why it’s deposited on the equator preferentially.”

Stereo imagery due to come to Earth in the next few days will help unravel topography across the heart region and the envelope of dark material around it. Scientists said the 3D images will help create a digital elevation model of much of Pluto’s hemisphere best observed by New Horizons.

Each pixel in the stretched color image of Pluto is about 18 miles (30 kilometers) across, and the true color photo from New Horizons’ long-range camera has a resolution of approximately 2.5 miles (4 kilometers).

The sharpest imagery from the flyby will have a resolution more than 50 times better.

“Right now, we don’t really know if (the heart region) is higher or lower than its surroundings,” Spencer said. “I get the impression that it’s lower, but stereo (images) will come in, and just getting high-resolution will really help with that.”

Spencer said the the first taste of New Horizons’ imagery offers revelations for Pluto scientists.

“We knew there was a big bright spot here because we could see it with the Hubble Space Telescope pictures,” Spencer said. “It was just a big bright blob, but you could tell it was there, so the overall distribution of the terrains and contrast of them is something we had some warning of.

“I don’t think we had appreciated how well those dark terrains wrapped around the equator in a discrete band that’s interrupted here,” Spencer said.

“Pluto’s got a lot of stuff going on,” Moore said. “We’ve tried to be cautious, and I think we’re just completely amazed by what a really diverse place this is, and it’s going to take some work to sort this out.”

A fresh estimate of Pluto’s size made by New Horizons’ science team also tells researchers a little about the icy dwarf’s atmosphere.

New Horizons was programmed to profile the tenuous atmosphere cocooning Pluto — which has about one hundred thousandth the pressure of Earth’s — on the outbound leg of Tuesday’s encounter. Data from those observations will not be available for at least a few days, said Randy Gladstone, head of the mission’s atmospheric science team from the Southwest Research Institute.

Gladstone said the atmospheric scientists have to get used to “delayed gratification” as data trickles down from New Horizons over the next few months.

But Pluto’s size, refined to a diameter of approximately 1,472 miles (2,370 kilometers), sets a bound on the thickness of the lowest, thickest layer of its atmosphere.

“That settles the question,” Gladstone said. “It’s a fairly shallow atmosphere. It means a lot of the struture of the atmosphere is very well defined now. All the weather and stuff, and any hazes that we see, are going to be concentrated in that area and the winds that blow across the surface.”

Charon, the often-forgotten sister world to Pluto, has its own, much older story to tell.

It is blanketed with craters, a sign Charon’s crust dates back billions of years. A giant chasm pictured on Charon may have developed as Charon cooled and shrunk soon after its formation, creating cracks and faults along its outer shell.

Scientists believe Charon formed after a collision between Pluto and a giant interloper.

A crude color map of Pluto’s moon Charon shows a vast dark marking near the north pole has a reddish hue, likely confirming a hypothesis that Charon’s frigid poles harbor deposits of frozen material trapped there as it streamed off of Pluto’s atmosphere.

“Pluto’s atmosphere is slowly leaking out into space and escaping, and as that drifts past the satellite, it can be temporarily trapped in ballistic trajectories hopping around the surface of the satellite (Charon),” said Will Grundy, an astronomer from Lowell Observatory.

Grundy said the atmospheric particles seem to be irradiated by solar radiation, forming a type of organic aerosol called tholins, which are normally reddish and appear on the icy moons of the gas giants in the outer solar system.

“The surface (of Charon) is too warm for it to stick, but if it hops around to the polar winter night side, it can stick,” Grundy said. “So you accumulate a bunch of escaped Pluto atmosphere, and then it’s processed by the energetic radiation in space and makes this class of material that we call tholins.”

According to Grundy’s theory, Charon catches the atmospheric gas flowing away from Pluto, and the aerosols can be trapped and frozen on the moon’s poles when mired in winter, which runs for decades in Pluto and Charon’s orbit around the sun.

“We’ve been looking at this dark polar spot for a long time, and sure enough, it is quite red,” said Grundy. “And the reason I said sure enough is because an idea has been bouncing around the science team for a couple of weeks now for a mechanism to do that, so it’s gratifying to see that it is, in fact, red.”

Tuesday’s make-or-break flyby only saw one side of Pluto up close, catching the world at one point in its 6.4-day rotation. New Horizons’ images of Pluto’s opposite hemisphere, which showed intriguing evenly-spaced dark splotches scattered across its equator, are much lower-quality.

Moore said he was happy with the section of Pluto encountered by New Horizons.

“Of course, if we could really change the laws of physics, we’d have the spacecraft make another pass in three days, and we’d see it.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.