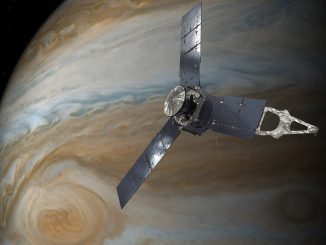

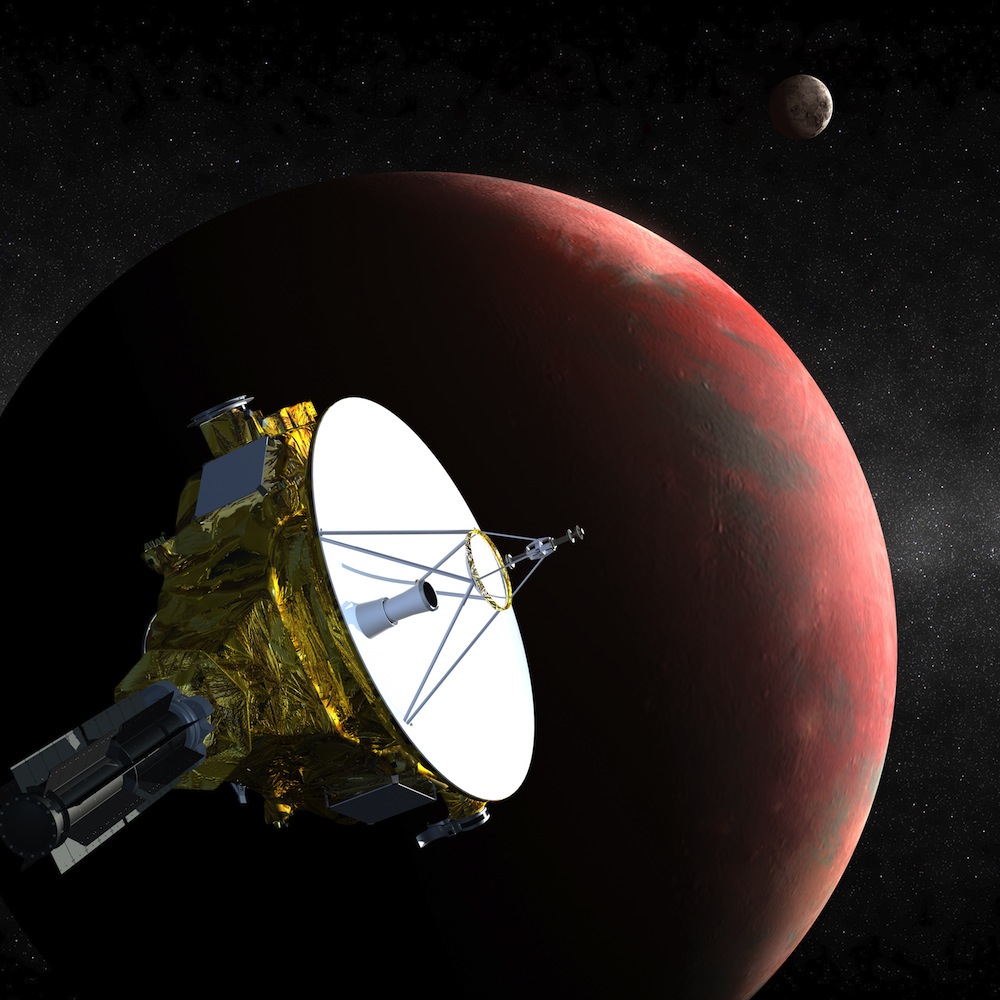

Pluto is in the sights of NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft, which started collecting around-the-clock science data Thursday as it speeds toward the first close encounter with the distant world in July.

The mission’s encounter phase formally started Thursday with the activation of the probe’s dust and plasma instruments to collect information on the environment at the outer frontier of the solar system.

Photos will come later, with the first imaging campaign of the Pluto encounter set to begin Jan. 25. The imagery will not be as sharp as photos from the Hubble Space Telescope until May, when New Horizons will start taking pictures showing Pluto in unprecedented detail through the mission’s July 14 flyby.

Thursday’s milestone came the same week as the ninth anniversary of the mission’s launch from Earth on Jan. 19, 2006. New Horizons is now about 134 million miles from Pluto, a fraction of the distance separating it from Earth.

“Our knowledge of Pluto is quite meager,” said Alan Stern, the mission’s principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, during a press briefing in November. “Despite the march of technology on the ground that has given us big telescopes, very powerful spectrometers, and even the Hubble Space Telescope in Earth orbit, we know very little about this world. In a real sense, it’s very much like our knowledge of Mars before our first mission to Mars 50 years ago.”

When New Horizons zooms past Pluto on July 14 — passing 6,200 miles above its icy crust — the spacecraft’s camera will be able to see surface features as small as 70 meters (230 feet) across.

If the probe was flying over New York, Stern said images from the New Horizons camera could allow scientists to count the lakes in Central Park and wharfs along the Hudson River.

That is a big improvement over photos of Pluto obtained by Hubble, which show the faraway dwarf planet just a few pixels across.

“You can’t see very much,” Stern said. “That’s the exciting part. From my standpoint, this is a Christmas present sitting under the tree that’s been waiting while we sped across the solar system to unwrap it. We are so looking forward to turning this very fuzzy little picture of this very distant and small planet into something real, and to do it by taking the world along.”

Images taken by the craft’s LORRI telescopic camera beginning Jan. 25 will help ground controllers guide New Horizons toward Pluto, which will still appear as a dot.

The best frame-filling images of Pluto will not come until July.

“This is much more than a single day,” said Hal Weaver, the mission’s project scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. “Of course, July 14, 2015, that’s the day that we reach the closest approach point to Pluto, and most of our best results will come from a few days around that time period.

“But I really want to emphasize that we’ll have lots of juicy science — historic science — accumulated well before the day of the closest approach,” Weaver said.

The milestone achieved Thursday — the start of Approach Phase 1 — is focused on taking pictures to home in on Pluto, allowing New Horizons to hit a narrow aim point designed to get the best observations of Pluto’s surface topography, composition and atmosphere.

Mission planners have allotted several opportunities for New Horizons to adjust its path toward Pluto, with the next chance for a course correction maneuver in mid-March, Stern said in an email to Spaceflight Now.

Weaver said New Horizons will also take background measurements of the particle and dust environment during Approach Phase 1, which runs through mid-April, to compare with data it collects at Pluto.

“As we move from later in April and into mid-June, that’s the time period where we start to get better than Hubble,” Weaver said. “We’ll also be doing deep searches for satellites (moons) and rings better than can be done with Hubble or any other observatory on the Earth, and then it just gets better and better and better as we’re closer and closer to Pluto.

“During the time of closest approach, it’s going to be astounding,” Weaver said. “It really will be. We’re going to be transforming Pluto from this pixelated image … into a completely new world, with complexity (and) diversity that we can’t even imagine.”

After it swoops past Pluto, New Horizons will continue taking data through the end of 2015 before taking aim on a new target in the Kuiper belt, a zone of little-studied worlds beyond the orbit of Neptune.

Then comes the data playback. It will take 16 months for all the spacecraft’s data on Pluto to stream down to the ground — a function of the volume of information scientists intend to collect and the probe’s distance from Earth.

“This is really quite an epic journey,” Stern said. “Three billion miles across the entirety of our planetary system, from the inner planets, to the middle solar system, to the third zone — the Kuiper belt — and for the first time. No voyage like this has been conducted since the epic days of Voyager, and nothing like it is planned again.”

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.