After an up-and-down week of intermittent contact with the LightSail satellite, the tiny spacecraft radioed home Saturday, giving engineers hope to deploy the experiment’s solar sail as soon as Sunday.

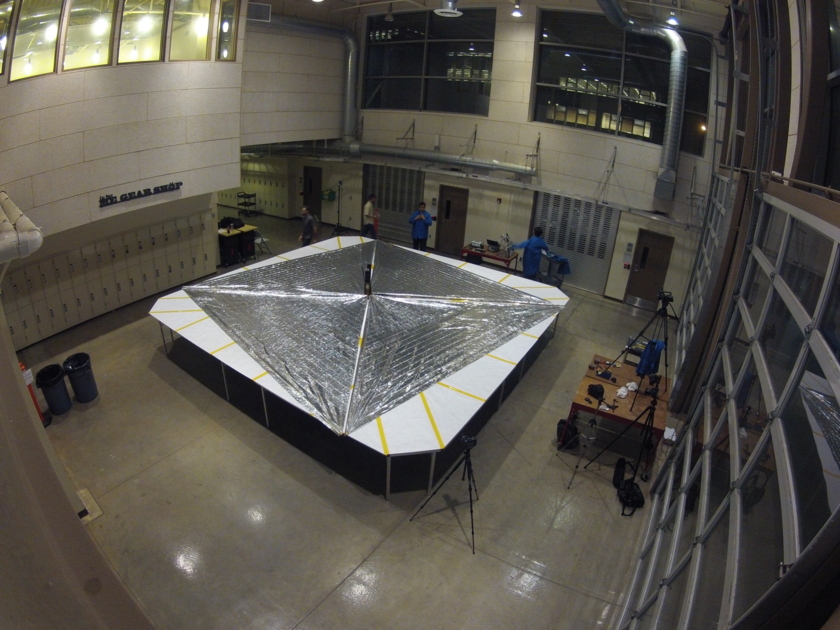

The deployment window opens at approximately 2:02 p.m. EDT (1802 GMT) Sunday, when LightSail is in range of ground stations, giving engineers real-time insight as the sail unfurls into a diamond shape covering 344 square feet.

The Planetary Society funded the construction of the shoebox-sized, 10-pound spacecraft with money from private donors. NASA paid for satellite’s launch May 20 as a secondary passenger aboard an Atlas 5 rocket.

Engineers at LightSail’s control center in California heard from the satellite Saturday for the first time since Wednesday, when managers commanded the spacecraft’s power-generating solar panels to open.

Telemetry from the spacecraft indicated LightSail’s four petal-like solar arrays opened as designed, but data showed its batteries were drawing almost no current from the solar panels.

Then LightSail unexpectedly stopped transmitting.

The satellite can communicate with its control team when it flies over ground stations in the United States, and flyovers Thursday and Friday yielded no contact, according to the Planetary Society’s website.

Engineers heard from LightSail on Saturday, when it sent back telemetry during two passes over a ground station in San Luis Obispo, California.

On the second pass, LightSail’s data stream indicated its batteries were charging, a promising sign that the satellite may be able to unfurl its solar sail Sunday.

If the batteries appear healthy Sunday, the ground team will give the go-ahead for deployment of the sail, according to Jason Davis, a blogger for the Planetary Society’s website who has provided daily updates on the mission’s progress.

Just a reminder: team absolutely has to see good battery data come in tomorrow before pulling the trigger on the sails. #LightSail

— Jason Davis (@jasonrdavis) June 6, 2015

The latest silence from LightSail came after officials went more than a week without contact with the satellite from May 22 to May 30. Engineers blamed a software glitch for the first interruption in communications, and an opportune blast of cosmic radiation zapped LightSail’s computer into a reset that brought the spacecraft back to life.

When engineers give the order, four metal booms will unwind like tape measures to coax out four triangular Mylar sails, which measure just 4.5 microns thick — one-fourth the thickness of an average trash bag, the Planetary Society said.

Cameras aboard LightSail should provide visual confirmation of the deployment, assuming everything goes according to plan.

LightSail is circling Earth in an orbit ranging in altitude between 220 miles and 435 miles each time around the planet. The CubeSat’s ground track across Earth carries it between 55 degrees north and south latitude.

The current mission was conceived as a technological pathfinder for a more ambitious satellite set for launch in 2016.

LightSail’s orbit is too low to test out the concept of solar sailing, which uses very subtle pressure from sunlight as a propulsion source, much like conventional sails catch wind at sea. Solar sails could enable future interplanetary missions to reach their destinations without carrying huge reservoirs of chemical propellant.

The pull from atmospheric drag is too high at LightSail’s current altitude.

The next LightSail CubeSat will go into a higher orbit after launching aboard a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket demonstrate its ability to harness sunlight to change its orbit around Earth. Another satellite will fly nearby to record imagery of the deployment.

The Planetary Society says the project’s total cost is $5.45 million, including funding for the follow-up mission next year. The group launched a Kickstarter page requesting donations from the public to cover $1.2 million of the cost.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.