The launch of the next Landsat Earth-viewing satellite in 2023 will be preceded by a smaller spacecraft to map the planet with an infrared camera under a new land imaging roadmap outlined by NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey.

The pair of new satellites will take over from Landsat 8, which launched in February 2013 and is stocked with enough fuel for a 10-year mission.

The White House’s budget request for fiscal year 2016, which begins Oct. 1, would fund the development of a new satellite named Landsat 9 for launch in 2023.

“Moving out on Landsat 9 is a high priority for NASA and USGS as part of a sustainable land imaging program that will serve the nation into the future as the current Landsat program has done for decades,” said John Grunsfeld, associate administrator for science at NASA Headquarters. “Continuing the critical observations made by the Landsat satellites is important now and their value will only grow in the future, given the long term environmental changes we are seeing on planet Earth.”

NASA has responsibility for building, launching and testing the Landsat 9 spacecraft. The USGS will take over control of the satellite after it is in orbit, then disseminate and archive the land imaging data.

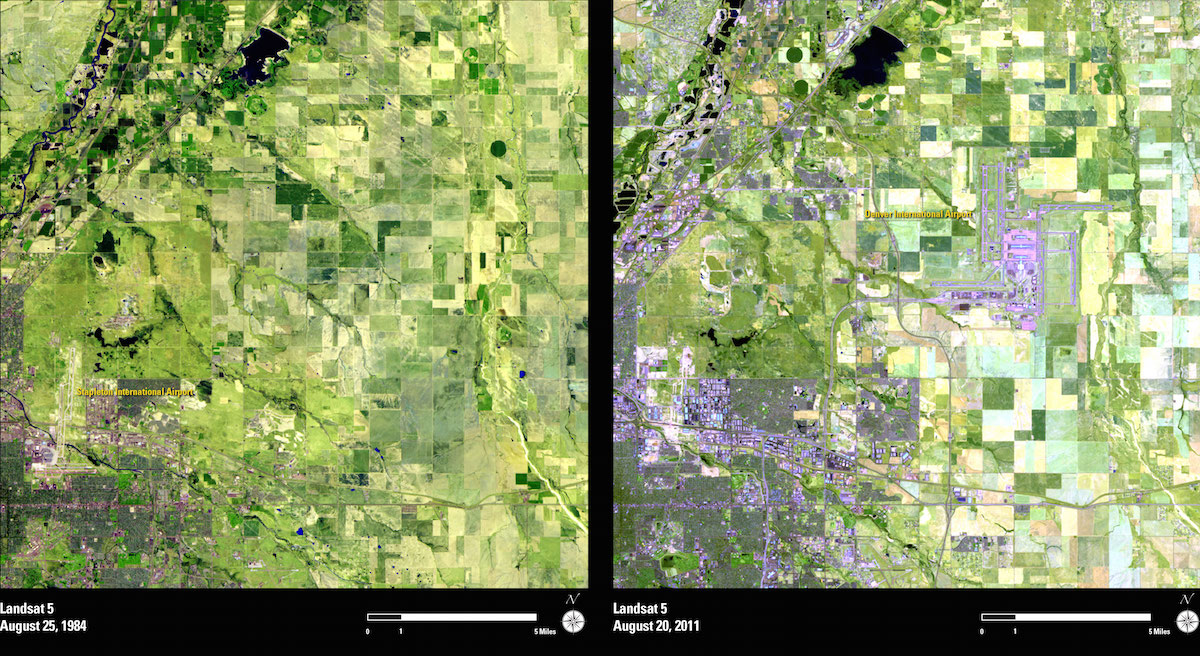

Landsat satellites have amassed a catalog of multi-spectral, moderate-resolution imagery of the world’s land masses since the first spacecraft in the series launched in 1972. Researchers and policy makers use Landsat data to track water resources, deforestation, agricultural production, urban sprawl, wildfire damage and the retreat of glaciers.

“This is the longest consistently processed time series from space that the (human) species has acquired,” said Michael Freilich, director of NASA’s Earth science division.

The sustained land imaging program outlined by the Obama administration is a strategic shift from how the federal government handled Landsat missions in the past.

“Up until now, the nation has only dealt with Landsat on sort of a ‘next mission’ basis,” Freilich told a NASA advisory board earlier this month. “The president’s fiscal year 2016 budget request has in it a sustainable land imaging system.”

The budget proposal calls for NASA and the USGS to immediately start development of two satellites to take over for Landsat 8 at the end of its mission.

“The president’s budget now has a full-blown land imaging system, multi-mission and multi-decadal, as opposed to just the next one,” Freilich said.

The first replacement craft would launch in 2019 with a thermal infrared imaging instrument, taking over for a sensor aboard Landsat 8 that has encountered trouble with its primary electronics chain.

Landsat 8 is designed for a five-year lifetime, but the satellite launched with a thermal infrared sensor guaranteed to last just three years. The thermal infrared instrument was a late addition to Landsat 8, and it is optimized to help manage water resources, especially in the drought-stricken western United States.

The infrared payload, known by the acronym TIRS, ran into a problem with its primary electronics system in December. Ground controllers switched the instrument to its backup electronics circuitry in March.

“The (thermal infrared) measurements are the weakest and least mitigable part of our land imaging measurements right now,” Freilich said.

NASA plans to build and launch a new thermal infrared instrument aboard a dedicated spacecraft and rocket as soon as possible, perhaps as soon as 2019, when the aging Landsat 7 satellite sent into space in 1999 should run out of fuel, according to Freilich.

The polar-orbiting “free-flyer” satellite will fly in formation with Landsat 8 or one of Europe’s Sentinel 2 land imaging satellites to bridge a gap in thermal measurements, Freilich said.

The next step will be Landsat 9, which should be ready for launch in 2023.

“We have started immediately the development of Landsat 9,” Freilich said. “Landsat 9 will be heavily based on Landsat 8 to the maximum extent possible. It will leverage all designs and spare parts, etc., from Landsat 8 with the exception of an upgraded thermal infrared instrument.”

With technological updates, the thermal sensor on Landsat 9 will be expected to last five years, not three.

“With a launch in 2023, Landsat 9 would propel the program past 50 years of collecting global land cover data,” said Jeffrey Masek, Landsat 9’s project scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “That’s the hallmark of Landsat: the longer the satellites view the Earth, the more phenomena you can observe and understand. We see changing areas of irrigated agriculture worldwide, systemic conversion of forest to pasture — activities where either human pressures or natural environmental pressures are causing the shifts in land use over decades.”

Congress has asked NASA if it can develop, build and launch Landsat 9 for less $650 million. Landsat 8 cost $855 million, and NASA officials have said a clone of the previous spacecraft would likely come in above the $650 million cap specified by lawmakers.

Under the Obama administration’s budget proposal, NASA is also authorized to study upgraded and miniaturized systems that could be incorporated in a follow-on Landsat 10 satellite for liftoff around 2030, with an aim to decide on Landsat 10’s design in 2019.

“We have recognized for the first time that we’re not just going to do one more, then stop, but that Landsat is actually a long-term monitoring activity, like the weather satellites, that should go on in perpetuity,” Masek said in a press release.

While Landsat 9’s launch in 2023 comes five years after its predecessor ends its five-year prime mission, officials expect Landsat 8 keep going into the 2020s, reducing the risk of a possible data gap.

“If you look at the on-orbit lifetimes of the Landsat missions, and indeed other related missions, a five-year design life goes out to typically about 11 years,” Freilich said.

“We have Landsat 8, which is performing well right now, and other international partners such as the Europeans with Sentinel 2A, which will launch this year in June, and Sentinel 2B, which will launch in 2016,” Freilich said. “Those missions could provide some mitigation to the loss of Landsat 8 potentially before Landsat 9 flies.”

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.