A rocket recovery team positioned off Florida’s East Coast is standing by for liftoff Sunday of a Falcon 9 launcher with a space weather satellite, but the demanding trajectory of the flight adds more unknowns to the company’s dicey endeavor to land the booster on a ship at sea, a SpaceX official said Saturday.

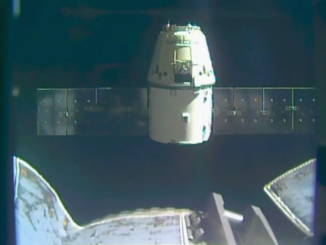

Aiming to perfect an unprecedented flyback maneuver with the Falcon 9 rocket’s first stage, SpaceX officials say they made changes to the booster after it crash landed on a specially-outfitted barge following a successful Jan. 10 launch to resupply the International Space Station.

The experiments are leading up to SpaceX’s plans to refurbish and reuse rocket boosters in a bid to slash the cost of launching satellites into orbit.

Hans Koenigsmann, SpaceX’s vice president of mission assurance, was careful to describe the rocket reusability experiment as a strictly secondary objective to the primary purpose of Sunday’s flight: dispatching NOAA’s $340 million Deep Space Climate Observatory toward a post a million miles from Earth.

“We had some adjustments after the last fairly hard landing on CRS-5,” Koenigsmann told reporters Saturday, referring to the fiery touchdown Jan. 10. “We fixed the problems.”

The crash destroyed the rocket, but the booster’s guidance system and engines apparently functioned as designed, steering the 14-story stage to the football field-sized barge before it ran out of hydraulic fluid to drive four aerodynamic stabilization fins in the final moments of the Falcon 9’s vertical descent.

SpaceX chief executive Elon Musk said the new launcher for Sunday’s flight carries “way more” hydraulic fluid to remedy the problem. At least it should explode for a different reason, Musk quipped on Twitter.

“We ran out of hydraulic fluid shortly after the landing burn started,” Koenigsmann said. “It was close. Personally, I feel this last time was an enormous accomplishment on the way to refurbishment and reusability of vehicles. I don’t see this as a failure at all. To me, it’s just a development step.”

The unoccupied landing platform — which survived the Jan. 10 landing attempt relatively unscathed — is stationed about 370 miles east-northeast of Cape Canaveral for Sunday’s launch, Koenigsmann said.

The weather in the landing zone should be favorable, according to a forecast issued by Mike McAleenan, the U.S. Air Force’s launch weather officer.

The outlook calls for mostly clear skies, good visibility, and waves of 2 to 4 feet. Surface winds will be out of the south at about 10 knots, McAleenan said.

Conditions at the Falcon 9’s launch site at Cape Canaveral are also predicted to be near-ideal Sunday, with a 90 percent chance of acceptable weather.

The modified barge is dubbed an autonomous spaceport drone ship and christened as “Just Read the Instructions” in a nod to planet-sized starships featured in science fiction author Iain M. Banks’ Culture novels, according to a report in Tor.com.

The particulars of Sunday’s launch mean SpaceX has to forego one of the three braking burns employed on the Falcon 9’s usual descent profile. Instead of re-firing a subset of the first stage’s nine kerosene-fueled Merlin engines three times, there will be two ignitions on the way back to Earth on Sunday.

“There are a couple of differences in the trajectory,” Koenigsmann said. “We will perform an entry burn and a landing burn. The speed of the stage coming in to entry is actually higher, and that … makes it a little less likely to succeed.”

The initial “boost-back” burn designed to drive the rocket back toward Florida has been omitted for Sunday’s mission.

“We had an early burn originally,” Koenigsmann said. “That burn is what we can’t do this time because all the propellant goes to the primary mission.

Sunday’s launch is set for 6:10:12 p.m. EST (2310:12 GMT) from Cape Canaveral’s Complex 40 launch pad. The timing of the blastoff two minutes after sunset could put on a sky show for spectators for hundreds of miles across Florida.

“We will flip the stage around after separation 180 degrees,” Koenigsmann said. “This is a sunset launch, and it’s probably very good to see. It’s probably very visible in the sky what we do, and you can see the first stage moving around. It will then coast, go through apogee, and will begin to descend, and that’s when the entry burn happens.”

The booster will reach an altitude of about 130 kilometers, or 80 miles, on an arcing path away from Cape Canaveral at an azimuth of about 70 degrees — roughly east-northeast.

After the entry burn, the rocket will drop through the atmosphere, using the friction of the air to slow down from around Mach 5, according to Koenigsmann. Once booster reaches a speed about 250 meters per second (559 mph) and extends its four hydraulically-actuated fins, it will re-ignite its center engine for a final time and deploy four carbon fiber and aluminum honeycomb landing legs to a span of 70 feet.

It should reach the ship about 9 minutes after liftoff, Koenigsmann said.

Technicians will be stationed a few miles away from the drone ship, ready to secure the rocket with welded steel shoes and vent leftover propellant and gases from the booster before it travels back to port in Jacksonville, Florida.

That’s assuming everything goes according to plan.

Koenigsmann stuck with Musk’s prediction of a 50 percent chance of sticking the landing before the Jan. 10 launch.

“To me, we fixed one problem that we had last time,” Koenigsmann said. “There might be issues ahead of us. Obviously, this is a difficult thing, and at the same time, the trajectory is more difficult (for this launch).”

He said the booster will encounter twice the aerodynamic pressure experienced during the Jan. 10 flight.

The next Falcon 9 launch scheduled for Feb. 27 will haul two communications spacecraft into geostationary transfer orbit for Eutelsat and Asia Broadcast Satellite. The high-altitude target orbit for the hefty telecom payloads will require nearly all of the Falcon 9 rocket’s first stage propellant load, and SpaceX plans to leave off the booster’s landing legs and not attempt a touchdown on the drone ship.

There are more launches later this year where SpaceX could attempt another shipboard landing, before eventually trying a touchdown on land.

“There’s continuous improvement,” Koenigsmann said. “We have plenty of opportunities over the next year to try this out and perfect the landing part.”

At the same time, Koenigsmann says he would like to see attention on the part of the launch going up rather than the piece coming down.

“It’s very important not to get distracted from the primary mission.”

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.