The UK’s Beagle 2 mission to Mars, which was lost in Christmas week 2003 during the final stages of its voyage to the red planet, has been rediscovered by NASA’s eagle eye in the Martian sky, the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO).

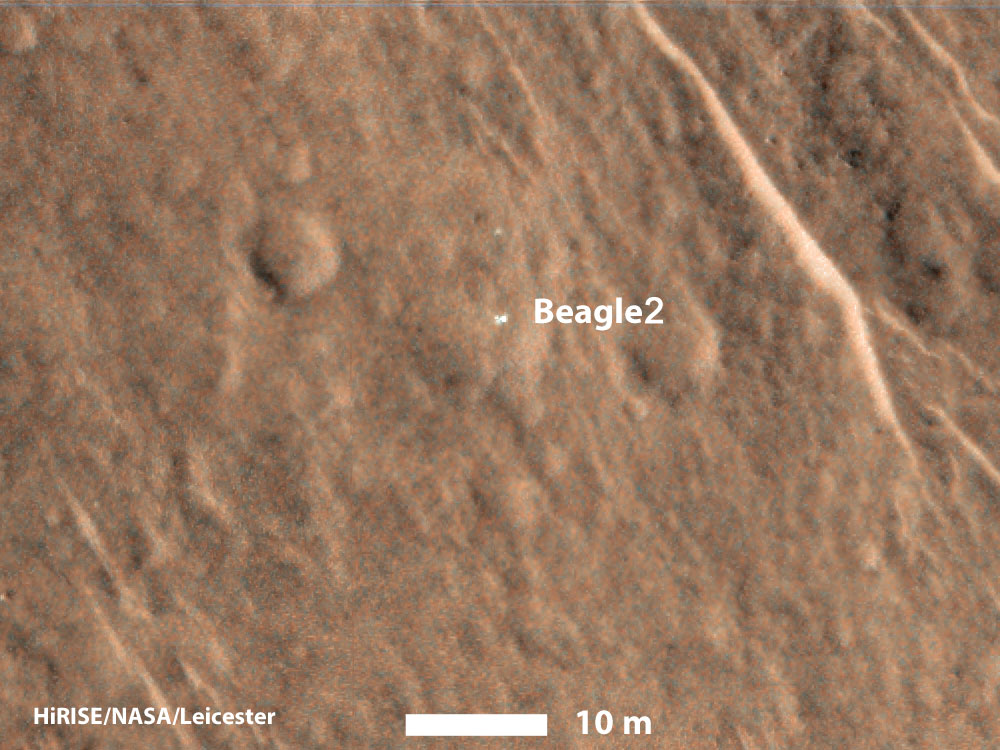

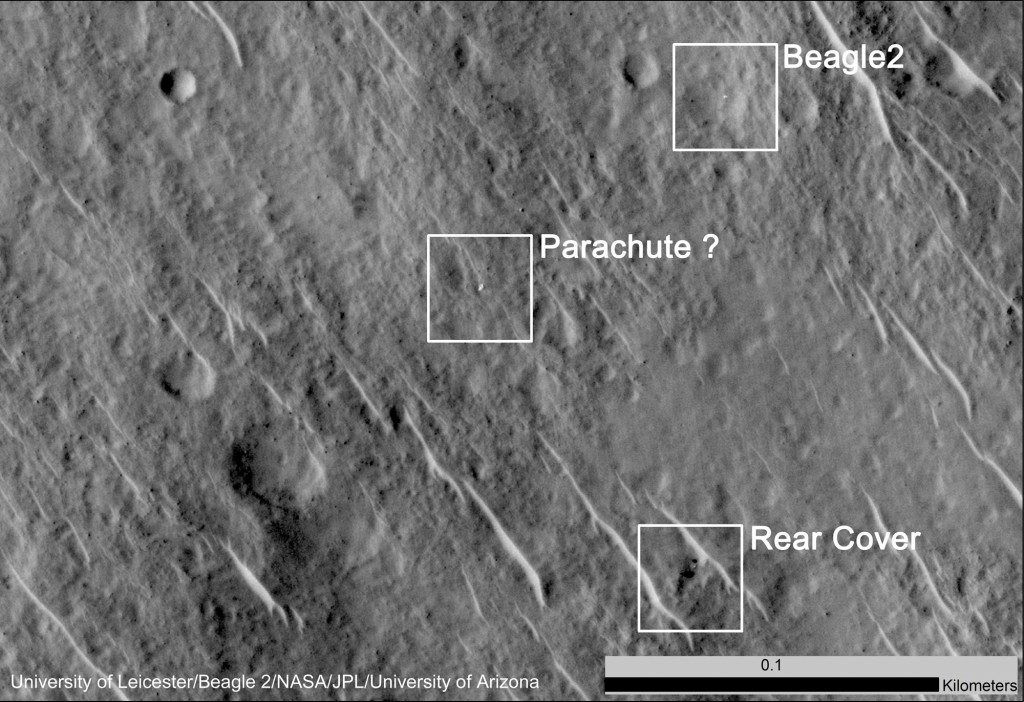

The lander has been identified as being partially deployed in an area of Mars called Isidis Planitia, a four-billion year old impact basin near the planet’s equator. The readily identifiable shape of at least two of its four solar panels unfurled, plus its base and lid looking a bit like a flower with petals, is visible in the images from MRO’s high resolution HiRISE camera.

The lander was first spotted by Michael Croon, a former member of ESA’s Mars Express operations team, in images taken by MRO in 2013. Croon alerted the Beagle 2 team in the UK and, after analysis and processing of further images, a team led by Professor Mark Sims of the University of Leicester, who was part of the original Beagle 2 team back in 2003, today revealed the images that help vindicate the mission.

“Overall I would personally say that Beagle 2 was a great success,” says Sims. “The images prove that it was the first European controlled landing on another planet.”

So what happened? Sims says that we cannot be sure yet from the images, which are fairly low resolution – HiRISE has a resolution of 30cm per pixel, and a fully opened up Beagle 2 would cover an area of just 1.9 x 1.6 metres.

“There is an amazingly long list of reasons [why Beagle 2 did not deploy fully],” says Sims “Whatever happened, it looks to have been just bad luck.”

There have been many theories over the years about what happened to Beagle 2. One possibility was that dust storms on Mars could have warmed the atmosphere, causing it to expand, meaning the parachutes could not function as planned and Beagle 2 would hit the surface too hard. Other scenarios included a leak in Beagle 2’s air bags that would have otherwise cushioned its landing, its backshell tangling with its parachute when it detached, or becoming tangled up in its parachute or airbags upon landing. Either way, without all its solar panels unfurled, its antenna could not deploy and communicate to scientists on Earth. Instead it just sat there, waiting for commands from Earth that never came, until it lost power.

The images show not just the lander, but also what appear to be its rear shell, with the pilot chute still attached and blowing in the Martian breeze, and its main parachutes. The lander stands out because of its highly reflective solar panels, the glint from which is seen changing with the angle of the Sun, while its low stature casts no shadows. The airbags are more difficult to spot, being of a similar red hue to the surface.

Beagle 2 was the brainchild of the late planetary scientist Colin Pillinger. Piggybacking on the European Space Agency’s Mars Express satellite that launched on 2 June 2003, which is still orbiting Mars to this day, Beagle 2 was a stationary landing craft rather than a rover. It was designed to last on the surface for at least 180 Martian days (a Martian day is 39 minutes longer than an Earth day), with a remit to investigate potential signs of life both past or present using its robotic arm, cameras, drill, X-ray spectrometer, a gas analysis package and even a ‘mole’ that could be deployed to burrow below the surface. However, after detaching from Mars Express and coasting for six days, it entered the atmosphere at a velocity of 20,000 kilometres per hour on Christmas Day 2003. Beagle 2 was not built with a communication system for the entry, descent and landing phase as there were no orbiters available to receive those particular signals and retransmit them to Earth. The first signal from Beagle 2 should have come from the ground, but there was only silence, and now we know why.

Although Beagle 2 did not operate on the surface as it was meant to, it is gratifying to know that it entered the atmosphere and safely reached the ground as planned, which alone is a success for the £48 million lander.

“The history books will have to be re-written,” says Dr David Parker, head of the UK Space Agency, “to show that Beagle 2 did land on Mars on Christmas Day 2003 after all.”