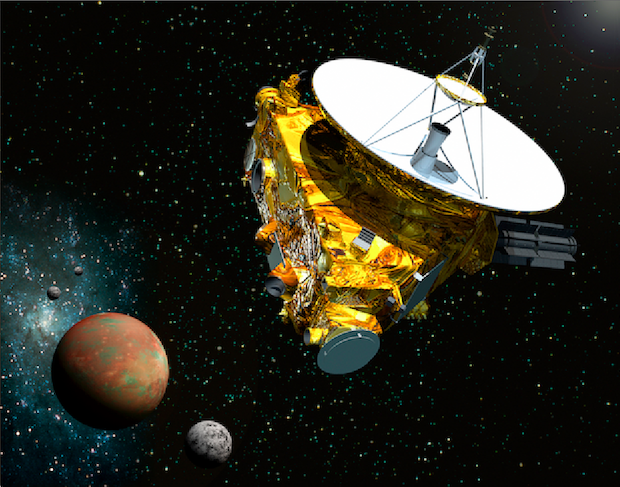

Speeding through the outer solar system after a nine-year trek from Earth, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft is awake and preparing for an encounter next summer with Pluto.

The probe’s mission control center in Maryland received signals from New Horizons at 9:53 p.m. EST Saturday (0253 GMT Sunday), confirming the spacecraft was active after rousing itself from hibernation more than 2.9 billion miles from Earth.

Traveling at light speed, the radio signal took 4 hours and 26 minutes to reach Earth, according to the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Md., home of New Horizons mission control.

“This is a watershed event that signals the end of New Horizons crossing of a vast ocean of space to the very frontier of our solar system, and the beginning of the mission’s primary objective: the exploration of Pluto and its many moons in 2015,” said Alan Stern, chief scientist on the New Horizons mission from the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo.

Saturday’s wakeup starts several weeks of preparations, testing and priming of New Horizons to formally start collecting scientific observations of Pluto and its surroundings on Jan. 15.

The robotic spacecraft is due to fly 6,200 miles from Pluto on July 14, 2015. It promises to bring the distant world into focus, replacing fuzzy images from the Hubble Space Telescope with high-resolution photos that will help scientists map craters, mountains and ice sheets believed to cover Pluto’s crust.

New Horizons has spent about two-thirds of its flight time in hibernation since the craft launched in January 2006. But officials periodically woke up the probe to test instruments and practice for the encounter at Pluto, when scientists have only one chance to get it right.

“Technically, this was routine, since the wakeup was a procedure that we’d done many times before,” said Glen Fountain, New Horizons project manager at APL. “Symbolically, however, this is a big deal. It means the start of our pre-encounter operations.”

The hibernations saved time, officials said, allowing scientists to focus on planning the mission’s future scientific endeavors instead of tracking its flight through the void of space.

In the next few weeks, ground controllers will prep New Horizons and its seven science instruments for the flyby.

“We’ll have about six weeks to do final preparations for the encounter,” said Alice Bowman, the New Horizons mission operations manager at APL. “We’ll be downlinking data — health and safety data — that was collected over this hibernation period. We’ll be doing memory checks on the different components on the spacecraft. We’ll be downlinking all the instrument data that we collected during hibernation.”

Engineers will upload the latest pointing and navigation data to New Horizons and wipe the memory of the probe’s data recorder, which will store information collected by the spacecraft’s sensors over the next year.

“When we first launched this spacecraft, I was amazed that we were going to have a 10-gigabit recorder space … Silly me, I thought for that scientists, that’s great. They’re going to have a hard time filling that up. Boy, was I wrong.”

New Horizons will spend the first three months of 2015 taking photos of Pluto to ensure the spacecraft is on track for the flyby. The probe’s instruments will also record the plasma and dust environment as it darts through the outer solar system for comparison with data gathered at Pluto, according to Hal Weaver, the New Horizons project scientist at APL.

“New Horizons is on a journey to a new class of planets we’ve never seen, in a place we’ve never been before,” Weaver said. “For decades we thought Pluto was this odd little body on the planetary outskirts; now we know it’s really a gateway to an entire region of new worlds in the Kuiper Belt, and New Horizons is going to provide the first close-up look at them.”

By May, a telescopic camera aboard the spacecraft will start taking images of Pluto with better clarity than possible with Hubble, which is stationed in Earth orbit.

“I expect we’re going to find lots of surprises,” Stern said. “That’s the most common thing on a first reconnaissance mission — we find things that we didn’t expect just by going and having a look with powerful instrumentation.”

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.