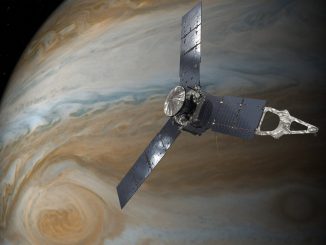

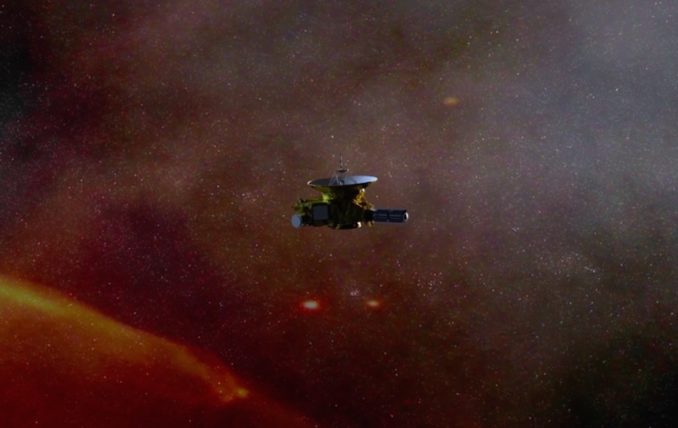

Speeding through the outer reaches of the solar system nearly 3.8 billion miles from Earth, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft has awakened from a five-and-a-half month slumber, ready for a second act after its 2015 flyby of Pluto with a New Year’s Day encounter with a primordial world set to become the most distant object ever explored.

The plutonium-powered probe woke up with an on-board timer late Monday, but the radio signal confirming New Horizons emerged from hibernation took nearly six hours to reach Earth, completing the journey at light-speed at 2:12 a.m. EDT (0612 GMT) Tuesday, officials said.

Alice Bowman, the New Horizons mission operations manager at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland, reported the long-lived spacecraft was operating normally, and all its systems came back online as expected, according to a statement.

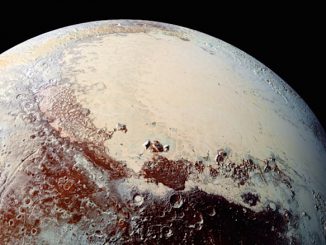

The mission’s July 14, 2015, flyby of Pluto produced stunning imagery, finding vast mountain ranges and revealing evidence of cryovolcanoes, glaciers, methane snow, and other surprising geologic activity.

After bending its trajectory following the visit to Pluto, New Horizons is now in an extended mission with a new destination in its sights. Managers ordered the 165-day hibernation, which began Dec. 21, to save fuel and give scientists time to script New Horizons’s approach to its next target.

Over the next two months, ground controllers will uplink commands to New Horizons to prepare the craft for a Jan. 1 encounter with an unexplored object in the Kuiper Belt, a ring of miniature worlds orbiting the sun beyond Neptune.

The object, officially named 2014 MU69 and nicknamed Ultima Thule, was discovered by astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope in 2014. Scientists estimate the object is about the size of a large city, and it appears reddish, but even the most powerful telescopes at Earth are not capable of resolving any details about the New Horizons mission’s next target.

Controllers will retrieve science data from earlier observations stored in the probe’s on-board memory, uplink memory updates, and complete a series of spacecraft and science instrument checkouts before New Horizons starts making long-distance navigation measurements using an on-board camera in August.

“Our team is already deep into planning and simulations of our upcoming flyby of Ultima Thule and excited that New Horizons is now back in an active state to ready the bird for flyby operations, which will begin in late August,” said Alan Stern, New Horizons principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

Researchers believe Ultima Thule has remained in its primordial state since the solar system’s early history 4.5 billion years ago. Comets that come from the far outer solar system originated in the same frozen, faint environment, but repeated passes near the sun have erased their ancient characteristics.

Scientists hope the New Horizons spacecraft’s discoveries at Ultima Thule will help their understanding of how the solar system formed and evolved over billions of years.

Uncertainties about Ultima Thule’s exact location will make navigation images taken by New Horizons’s own camera critical for fine-tuning the spacecraft’s trajectory later this year. A series of course-correction opportunities are planned from October through December to steer New Horizons toward its target.

Astronomers observing Ultima Thule from the ground using the object’s occultation of stars have concluded the mini-world likely has an elongated shape, and it may consist of two or three separate components, including a small moonlet orbiting nearby.

Ultima Thule’s diminutive size, coupled with New Horizons’s fast closing speed, will keep the probe’s primary science camera from resolving its shape, and the number of objects there, until the final weeks and days before the encounter.

Mission planners have developed two flyby trajectories, with scientists preferring to send New Horizons as close as 2,175 miles (3,500 kilometers) from Ultima Thule, assuming scans of the flight path during the spacecraft’s approach turn up no hazards, such as moons or a debris ring. Managers could decide as late as mid-December to re-target an aim point more than 6,000 miles (10,000 kilometers) away if they detect danger, sacrificing some scientific data and high-resolution imagery for safety.

For comparison, New Horizons zipped by Pluto at a range of around 7,800 miles (12,500 kilometers). Thanks to the closer flyby distance, scientists expect to see more detail in New Horizons’s imagery of Ultima Thule than they saw at Pluto.

As of Tuesday, New Horizons was approximately 162 million miles (262 million kilometers) from Ultima Thule — located a billion miles (1.6 billion kilometers) beyond Pluto — and traveling 760,200 miles (more than 1.2 million kilometers) closer each day.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.