United Launch Alliance chief executive Tory Bruno said Thursday the company will offer more rides for CubeSats aboard future Atlas 5 rocket flights, and give some away for free, in a bid to tap into a growing market of small satellites with applications in education, scientific research and commercial business.

The Colorado-based company will begin by offering six CubeSats free trips to orbit on two Atlas 5 launches beginning in 2017, riding up with much larger payloads for customers who purchased the bulk of the rocket’s capacity. Bruno said ULA intends to eventually offer CubeSat capacity on nearly every flight of the Atlas 5 and the Vulcan rocket, its successor.

“Starting a year-and-a-half from now, we’re going to start placing on our Atlas rocket a standard CubeSat carrier with as many as 24 berths for CubeSats,” Bruno said Thursday in an announcement at the Colorado State Capitol in Denver.

According to Bruno, ULA’s CubeSat initiative will be a boon to universities seeking affordable ways to build and launch tiny satellites for research missions and as an education tool for students who develop and operate the spacecraft.

The University of Colorado in Boulder will get the first chance to put a CubeSat on an Atlas 5 rocket for free.

“This program is open to all universities nationwide, and we’re delighted that CU-Boulder students have been offered the first free CubeSat launch slot in 2017,” said Philip DiStefano, chancellor at the University of Colorado in Boulder.

More than 300 CubeSats have launched on rockets from around the world since 2003. Engineers at Stanford University and California Polytechnic State University first conceived of the small-scale standardized satellite design in 1999.

The basic CubeSat is a 10-centimeter (4-inch) cube with a volume of exactly one liter and a mass of less than 1.33 kilograms (2.93 pounds). Since the CubeSat’s introduction 15 years ago, designers have deployed bigger versions made of two, three, or more 10-centimeter form factors.

As miniaturized technologies open new possibilities for small satellites, companies have built business models relying on fleets of dozens or hundreds CubeSats, as universities look to CubeSats as teaching tools in science, technology, engineering and mathematics, or STEM, fields.

“The ability to provide science and engineering students with the opportunity to fly the satellites they build is an invaluable motivational and educational tool, and we want to compliment ULA for being so supportive of STEM education and hands-on engineering opportunities,” DiStefano said in remarks at the Colorado Capitol.

“This is exactly the kind of collaborative innovation that we celebrate in Colorado,” said Colorado Lt. Gov. Joseph Garcia. “Here, we have a Colorado company giving Colorado students at a Colorado university an unbelievable opportunity to send a satellite into space. What a great day for our state.”

With up to 24 CubeSat slots per Atlas flight, depending on whether the payloads are single or multiple-unit CubeSat designs, ULA’s rideshare initiative could offer hundreds of CubeSat flight opportunties per year, and some of them at no cost.

“Our Atlas rocket flies very, very often, so in a year-and-a-half, all of a sudden there are going to be rides to space, and there will always be free berths for STEM applications for universities,” Bruno said. “My vision is we will transition to a point where nearly every Atlas rocket is carrying a standard carrier with these CubeSats.

“We fly Atlas 10 times a year or more,” Bruno said. “We are going to more than double the entire worldwide capacity for a CubeSat to get to space.”

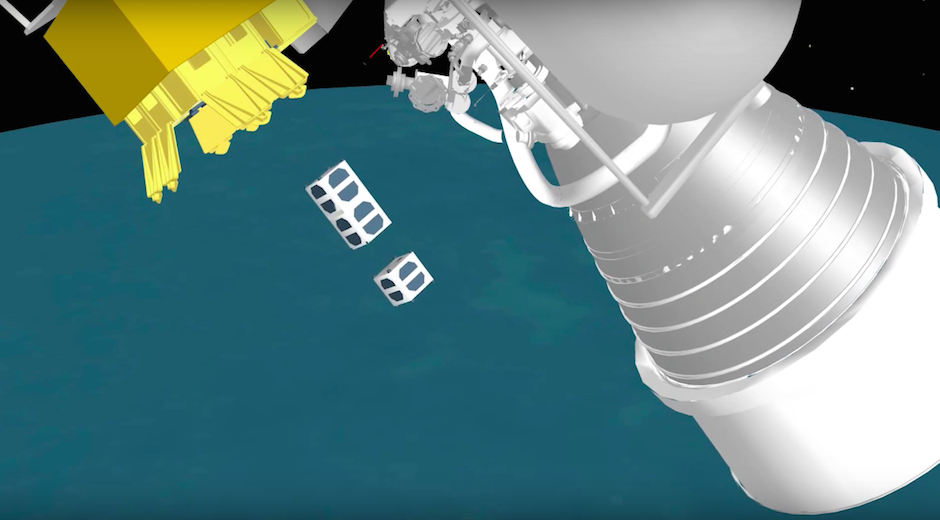

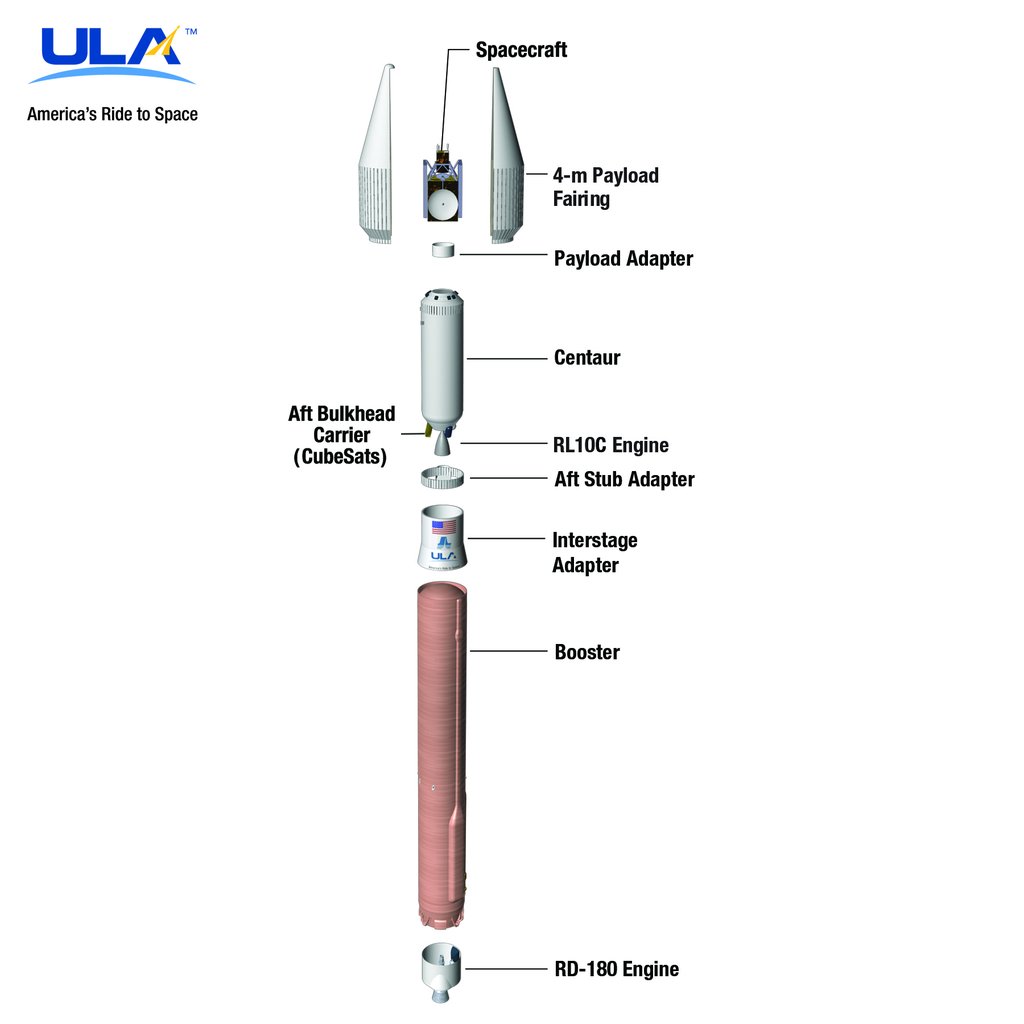

The CubeSats will be spring-ejected from ULA’s Aft Bulkhead Carrier bolted to the rear end of the Atlas 5’s Centaur upper stage, the same adapter system that has already ferried flocks of CubeSats into orbit for NASA and the U.S. military on several missions. The location of the carrier keeps the secondary passengers from interfering with the mission’s prime payload, which is mounted to the top of the rocket.

ULA has launched 55 CubeSats to date, and another set is scheduled for launch inside Orbital ATK’s Cygnus spacecraft Dec. 3 for deployment from the International Space Station.

“Every year, these small satellites are becoming more and more capable, doing more missions, having greater potential, but there’s a problem,” Bruno said. “It’s very difficult for CubeSats to find a ride to space, to actually get there, to do their research, to do their mission.”

Bruno said ULA will solicit suggestions from educators and students for a name for the CubeSat launch program, and the winner will secure a free ride for their institution’s CubeSat as the second no-cost launch after the University of Colorado’s payload.

ULA said in a press release that university representatives should email proposed names for the CubeSat program and express their interest to the company by Dec. 18. A formal request for proposals will be released in early 2016, and universities selected for the CubeSat launch initiative will be announced in August 2016, ULA officials said.

An auxiliary payload integration contractor will orchestrate the selection process for ULA, according to Lyn Chassagne, a company spokesperson.

“We anticipate a team of senior parters and ULA leaders will make the final selection,” Chassagne wrote in an email to Spaceflight Now. “ULA also may ask leaders from the aerospace industry and the U.S. government to participate on the selection team.”

ULA’s new effort to address the burgeoning growth of the CubeSat launch market follows NASA’s CubeSat Launch Initiative, which culls CubeSats from universities and research institutions through competitions similar to the method apparently envisioned by ULA.

NASA pays for the launch of CubeSats under the agency’s Educational Launch of Nanosatellites, or ELaNa, program.

Like ULA’s CubeSat program, ELaNa spares universities from shouldering the costs of launching CubeSats, which can run up to $500,000, much more than the investment for building the spacecraft itself.

ULA’s announcement Thursday comes on the heels of news from Seattle-based Spaceflight Industries in September that it purchased from SpaceX a full Falcon 9 rocket to fly from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California in 2017 with a cluster of lightweight satellites and CubeSats.

Spaceflight Industries, which aggregates CubeSats and secondary payloads to fly on launchers around the world, plans to launch its first Sherpa multi-payload adapter ring on a test flight aboard a Falcon 9 rocket in 2016, before filling up the Falcon 9’s entire capacity on the 2017 mission.

Some companies are developing light-class launchers carry up CubeSats and other small satellites on dedicated flights, allaying complaints from CubeSat developers about the pitfalls of the rideshare model, which gives CubeSat engineers little or no control over their final orbit or launch schedule.

“The effect that has had is really stunting the growth of CubeSats and the other satellites — the smaller satellites — that they can enable through that research that they do, because it’s so hard to get to space,” Bruno said. “We’re going to change that. We’re going to completely transform the availability of space for CubeSats, for their commercial applications, and most importantly for the research and STEM (education) opportunities that they provide.”

While the program unveiled by ULA on Thursday will give CubeSats dramatically more rides into orbit, the Atlas 5’s big payloads owned by the U.S. military, NASA and commercial operators will still drive when and where the CubeSats launch.

NASA announced in October contracts with Virgin Galactic, Rocket Lab USA and Firefly Space Systems for demonstration launches of their new small rockets specifically sized for CubeSats.

In the meantime, companies like ULA, Spaceflight Industries, and the space station’s commercial CubeSat deployer owned by NanoRacks are among the primary means of serving the U.S. CubeSat market.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.