A cache of critical cargo stowed inside a solar-powered Japanese resupply freighter is speeding toward a rendezvous with the International Space Station after a successful launch Wednesday.

Among the supplies inside Japan’s fifth H-2 Transfer Vehicle are spare parts for the space station’s water filtration system, spacesuit components and medical gear to replace items lost during a SpaceX rocket failure in June.

While the space station has weathered recent cargo launch failures without sacrificing the crew’s health or scientific objectives, Wednesday’s flight took on extra importance because it is the last resupply run expected to fly to the U.S. segment of the complex until at least December.

“We need to fly HTV to continue to operate on-board, so it’s of significant need,” said Mike Suffredini, NASA’s space station program manager. “We’ve got resources, I think, into November right now, so (HTV) give us resources into the next year.”

A commercial Cygnus freighter owned by Orbital ATK is scheduled to launch from Cape Canaveral on Dec. 3 aboard a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket. It will be Orbital ATK’s first space station flight since an Antares rocket crashed seconds after liftoff in October 2014, grounding the privately-developed booster.

NASA officials do not expect the next SpaceX supply mission to fly before December, Suffredini said. He added that NASA has asked SpaceX not to put the next Dragon cargo flight to the space station first in line when the Falcon 9 returns to flight after a June 28 mishap traced to a weakened bracket in the rocket’s second stage.

The 33-foot-long HTV cargo delivery craft blasted off at 1150:49 GMT (7:50:49 a.m. EDT) Wednesday, roughly the moment Earth’s rotation aligned the Tanegashima Space Center with the path of the high-flying research lab’s orbit.

After a smooth countdown, the 186-foot-tall H-2B rocket lit two hydrogen-burning LE-7A main engines and four powerful solid rocket boosters and climbed away from Launch Pad No. 2 at Tanegashima’s Yoshinobu launch complex nestled on an island in southern Japan.

Lighting up its surroundings with a pyrotechnic display of brilliant orange exhaust, the rocket raced into the night sky over the launch base, where it was 8:50 p.m. local time Wednesday.

The four strap-on boosters jettisoned to call into the Pacific Ocean about two minutes after liftoff, followed by release of the two-part payload fairing enshrouding the HTV supply ship. A second stage engine took over the launch sequence and fired more than eight minutes to propel the HTV into orbit about 14 minutes after liftoff.

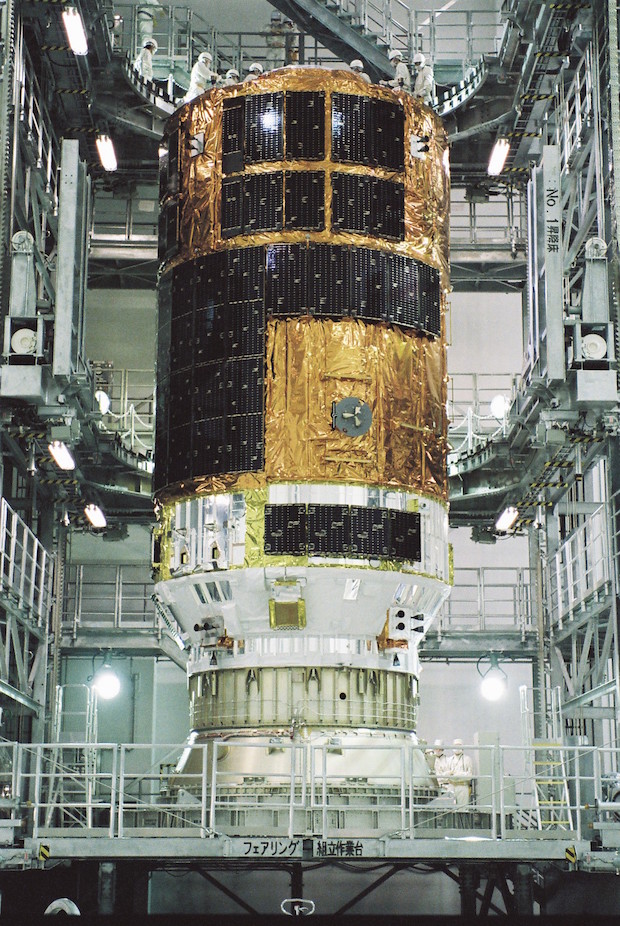

The HTV cargo craft, shaped like a soda can and covered in power-generating solar cells, separated from the rocket’s second stage moments later, kicking off a five-day pursuit of the space station set to conclude Monday.

Nicknamed Kounotori 5, the Japanese word for white stork, the HTV will guide itself to the space station with a series of engine burns, then acquire the huge 450-ton research lab with a suite of laser navigation sensors for the final rendezvous profile.

Approaching from underneath the station, the Japanese cargo craft will slow its speed and hold about 30 feet from the complex, close enough to grapple the free-floating spaceship with the outpost’s robotic arm. Japanese flight engineer Kimiya Yui will control the robot arm during the maneuver to capture the HTV.

Once the supply vessel is bolted to the space station’s Harmony module, the astronauts will unpack more than 8,000 pounds of cargo packed inside the HTV’s pressurized cabin.

The breakdown of the supply load includes 3,101 pounds of crew supplies, such as food, clothing and items to restock the space station’s pantries. Another 2,753 pounds of gear will support the space station’s research regimen, focusing on how the human body responds to extended stays in orbit and the behavior of super-hot melts in microgravity.

The experimental hardware includes a high-temperature furnace and a platform made by NanoRacks to host commercial payloads on an exposed facility outside the space station.

A package of CubeSats strapped inside the HTV will be ejected from a special deployer mounted on the end of the station’s Japanese robot arm in the coming months.

A refrigerator-sized rack designed to host future small plug-and-play research payloads will also be transferred over to the space station from the HTV’s cargo compartment.

The HTV is carrying 172 pounds of spacewalk equipment and 119 pounds of computers, printers, batteries and chargers.

The remaining 1,915 pounds of cargo inside the HTV’s internal cabin are parts to maintain and improve the space station, including a new galley conceived to be a one-stop location to help crew members prepare meals.

“A lot of times the ISS is described as a four-bedroom house or a five-bedroom house, and that’s very true, but the one thing the ISS doesn’t have is a kitchen,” said Royce Renfrew, NASA’s lead flight director for the HTV 5 mission. “It has the ability for the crew to get water out of a potable water dispenser in the lab. There are suitcase-sized food warmers that are scattered around, there are a couple of what are called MERLINs, which are refrigerators where they can keep their food cold when they want it cold. But it’s not all consolidated in one space.

“So we’re going to get a kitchen — a galley rack — that’s going to go in the (Unity) module,” Renfrew said. “We’ll move the potable water dispenser there. It comes up with its own little refrigerators called MERLINs, and it has its own food warmers. so it has water, it has a refrigerator, and it has a stove, if you want to think of it that way. That will all be in one place in (Unity), and I’m sure the crew will appreciate having that.”

An astrophysics sensor designed to search for elusive evidence of dark matter is latched inside the HTV’s external cargo hold. The station’s robotics systems will transfer the dark matter instrument to a port on the Japanese Kibo laboratory’s exposed experiment platform shortly after the HTV’s arrival.

Led by Japanese scientists, the Calorimetric Electron Telescope, or CALET, instrument will search for sources of high-energy cosmic rays in local regions of the Milky Way galaxy. Researchers hope data from the sensor will include signatures of dark matter, the unexplained material that makes up more than one-quarter of the universe.

“To ascertain the existence of dark matter, electromagnetic waves flying about in space, as well as cosmic rays and high energy gamma rays (both rays hold energy with much higher than these of ultraviolet rays and X-rays) should be closely examined,” explains an overview of the CALET experiment on JAXA’s website.

Scientists expect the cosmic ray detector to operate between two and five years.

The resupply ship will turn into a trash collector at the end of its mission, when astronauts will replace the items brought to the space station with garbage. The HTV will depart from the station in late September and plunge back into Earth’s atmosphere for a destructive re-entry over the South Pacific Ocean.

Japanese engineers are constructing at least four more HTV spacecraft for launch through 2020. The Japanese delivery craft is the space station’s largest resupply ship currently in service, and NASA is negotiating with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency to procure more HTVs for flights in the 2020s, Suffredini said.

NASA has committed to continue the space station program until at least 2024.

“It’s got a very large volume inside so we utilize it quite a bit for up-mass, but also for trash,” Suffredini said of the HTV design. “We fill it and we stuff it when we’re done, and when we close the hatch, it’s completely full all the way to the hatch, so it’s very, very good in terms of taking off trash.”

The next HTV mission is set for late 2016, followed by flights about once per year through the rest of the decade.

“HTV is on the larger side for a resupply vehicle, which is good,” Suffredini said. “You don’t fly as many flights with a larger vehicle, so that’s significant. It’s pressurized volume is very big. It will be the only vehicle that will carry racks to orbit, so that’s a unique role that it will have for us in the future. We intend to retain that capability because nobody else can do it.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.