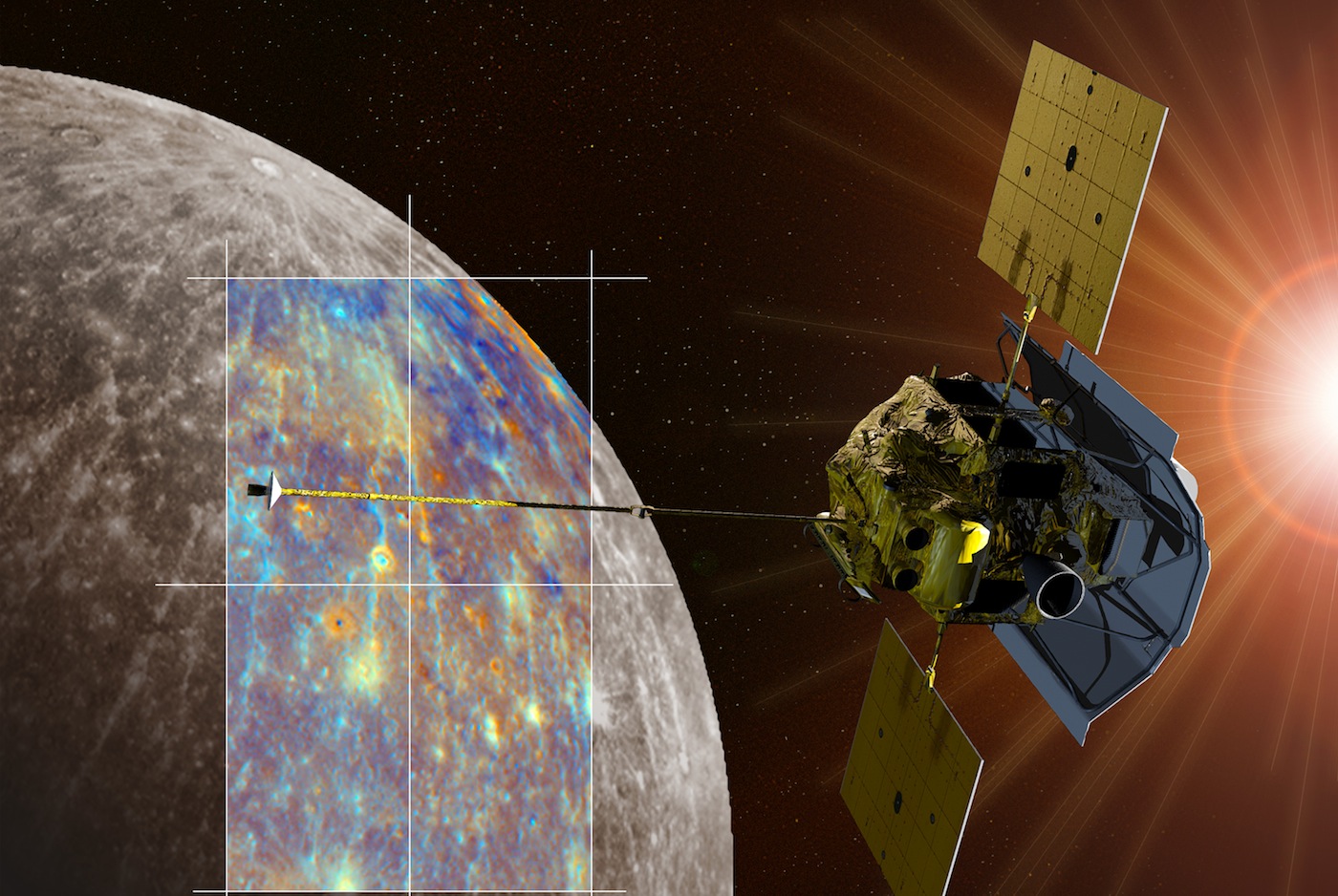

Running low on fuel after completing the first global survey of Mercury, NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft could get an extra month of time at the solar system’s innermost planet thanks to a crafty new way of using helium gas to temporarily forestall the mission’s end next year.

The bonus time would allow scientists to study the tortured world’s magnetic field and ice deposits hidden inside craters near Mercury’s north pole, officials said.

MESSENGER is about to run out of hydrazine fuel that feeds the spacecraft’s rocket thrusters to adjust the probe’s orbit around Mercury. Without the propellant, MESSENGER will eventually crash into Mercury when gravity pulls the satellite out of orbit.

Mission controllers expected MESSENGER would plunge into Mercury at the end of March 2015, but engineers devised a way to use helium gas carried aboard the spacecraft to pressurize its propulsion system to keep the probe in orbit for up to an additional month.

“MESSENGER has used nearly all of the onboard liquid propellant. Typically, when this liquid propellant is completely exhausted, a spacecraft can no longer make adjustments to its trajectory. For MESSENGER, this would have meant that we would no longer have been able to delay the inevitable impact with Mercury’s surface,” said Dan O’Shaughnessy, MESSENGER mission systems engineer at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland.

MESSENGER became the first spacecraft to orbit Mercury when it arrived at the fleet-footed planet in March 2011. The mission blasted off from Earth aboard a Delta 2 rocket in August 2004.

MESSENGER — or the Mercury Surface, Space Environment, Geochemistry and Ranging mission — completed flybys of Earth and Venus to spiral into a path closer to the sun before braking into orbit around Mercury in 2011.

The mission was supposed to last one Earth year after it arrived at Mercury, but NASA approved two extensions to keep MESSENGER operating until early 2015, when the spacecraft’s fuel supply was expected to run out.

“However, gaseous helium was used to pressurize MESSENGER’s propellant tanks, and this gas can be exploited to continue to make small adjustments to the trajectory,” O’Shaughnessy said in an update posted on MESSENGER’s mission website.

MESSENGER was the first spacecraft to visit Mercury since NASA’s Mariner 10 probe made a series of brief encounters with the planet in 1974 and 1975.

Engineers plan to vent MESSENGER’s highly pressurized helium gas through the spacecraft’s thrusters to impart small forces and keep the probe in orbit.

Some small satellites and rockets use cold nitrogen gas to maintain their orientation in space, but MESSENGER’s engineers believe the craft will be the first to use cold gas helium as an ad hoc source of propulsion.

“The team continues to find inventive ways to keep MESSENGER going, all while providing an unprecedented vantage point for studying Mercury,” said Stewart Bushman, MESSENGER’s lead propulsion engineer. “To my knowledge this is the first time that helium pressurant has been intentionally used as a cold gas propellant through hydrazine thrusters. These engines are not optimized to use pressurized gas as a propellant source. They have flow restrictors and orifices for hydrazine that reduce the feed pressure, hampering performance compared with actual cold gas engines, which are little more than valves with a nozzle.”

The pressurized helium will only buy MESSENGER a few more weeks of time to gather data on Mercury.

“Propellant, though a consumable, is usually not the limiting life factor on a spacecraft, as generally something else goes wrong first,” Bushman said in a post on MESSENGER’s website. “As such, we had to become creative with what we had available. Helium, with its low atomic weight, is preferred as a pressurant because it’s light, but rarely as a cold gas propellant, because its low mass doesn’t get you much bang for your buck.”

MESSENGER is on track for an orbit-raising maneuver with its hydrazine-fueled thrusters Jan. 21 to extend the mission’s life through March. The helium should keep MESSENGER going through most of April, officials said.

During the final phase of MESSENGER’s mission, the craft will collect data from as close as 5 miles above Mercury. Prime research targets for MESSENGER’s final weeks include close-up observations of water ice trapped in the frigid bottoms of Mercury’s polar craters, where temperatures hover near absolute zero despite the planet’s proximity to the sun.

“During the additional period of operations, up to four weeks, MESSENGER will measure variations in Mercury’s internal magnetic field at shorter horizontal scales than ever before … Combining these observations with those obtained earlier in the mission at slightly higher altitudes will allow the depths of the sources of these variations to be determined,” said Haje Korth, instrument scientist for MESSENGER’s magnetometer.

“In addition, observations by MESSENGER’s neutron spectrometer at the lowest altitudes of the mission will allow water ice deposits to be spatially resolved within individual impact craters at high northern latitudes,” Korth said.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.