High concentrations of manganese oxides found in Martian rocks by NASA’s Curiosity rover indicate the red planet’s atmosphere once had much more oxygen than than previously thought, scientists said Monday.

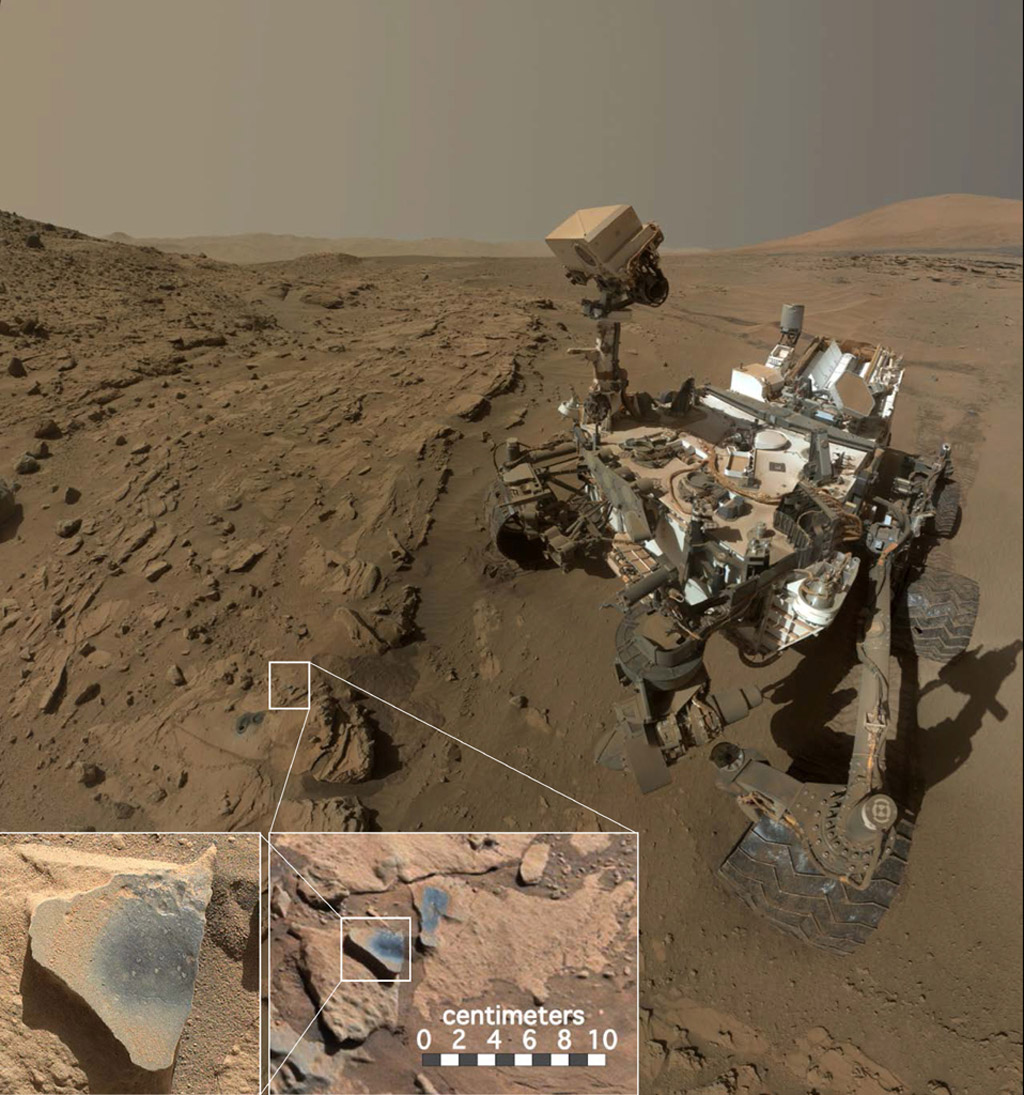

Geologists scrutinizing data from Curiosity’s ChemCam instrument, which takes remote measurements of rocks with a laser, discovered the manganese oxides in mineral veins, or cracks, embedded in sandstones at a research site named “Windjana” the rover visited in 2014.

Windjana is one of many geological sites studied by Curiosity since its landing in Gale Crater in August 2012.

Researchers already believed the vein-like features come from minerals left behind by water, and the presence of manganese oxides — chemicals that must have formed in an oxygen-rich atmosphere — seemingly ties the ancient wet environment to a time billions of years ago when more oxygen was in the air.

“The only ways on Earth that we know how to make these manganese materials involve atmospheric oxygen or microbes,” said Nina Lanza, a planetary scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, which led development of Curiosity’s ChemCam instrument. “Now we’re seeing manganese oxides on Mars, and we’re wondering how the heck these could have formed?”

The atmospheric oxygen explanation for the manganese oxides is more plausible than a biological origin, scientists said in an announcement Monday accompanying the finding’s publication in the journal Geophysical Research Papers.

“These high manganese materials can’t form without lots of liquid water and strongly oxidizing conditions,” Lanza said in a statement issued by the the Los Alamos National Laboratory. “Here on Earth, we had lots of water but no widespread deposits of manganese oxides until after the oxygen levels in our atmosphere rose due to photosynthesizing microbes.”

Scientists are still struggling to explain how the atmosphere of ancient Mars may have been enriched with oxygen, but one theory is it came from the water on the planet’s surface, NASA said in a press release.

“One potential way that oxygen could have gotten into the Martian atmosphere is from the breakdown of water when Mars was losing its magnetic field,” said Lanza, the lead author of a paper outlining the results in Geophysical Research Letters. “It’s thought that at this time in Mars’ history, water was much more abundant.”

As the Martian magnetic field eroded, cosmic and solar radiation penetrated to the planet’s surface, destroying water molecules and splitting them into hydrogen and oxygen. The lighter hydrogen atoms escaped into space, but the heavier oxygen atoms were trapped by Mars’ gravity, becoming embedded in rocks, scientists said.

That is what gives Mars its characteristic rust color. But manganese oxides need more oxygen to form than the widespread red iron oxides.

In a joint statement released by NASA and LANL, Lanza added that it is hard to determine exactly how the Martian atmosphere might have got its oxygen.

“But it’s important to note that this idea represents a departure in our understanding for how planetary atmospheres might become oxygenated,” Lanza said.

“Abundant atmospheric oxygen has been treated as a so-called biosignature, or a sign of extant life, but this process does not require life,” the joint statement said.

The manganese deposits are not limited to the Curiosity rover’s exploration zone in Gale Crater. NASA’s long-lived Opportunity rover recently discovered similar material in Meridiani Planum on the other side of Mars.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.