A small spacecraft attempting to become the first privately-funded probe to accomplish a controlled landing on the moon likely fell to the lunar surface after running out of fuel Tuesday, according to the Japanese company ispace, which managed the mission.

The Japanese company lost communication with the Hakuto-R lander moments before its scheduled touchdown in Atlas crater, a 54-mile-wide (87-kilometer) impact basin on the near side of the moon. The spacecraft was on final approach for an automated landing at 12:40 p.m. EDT (1640 UTC) Tuesday.

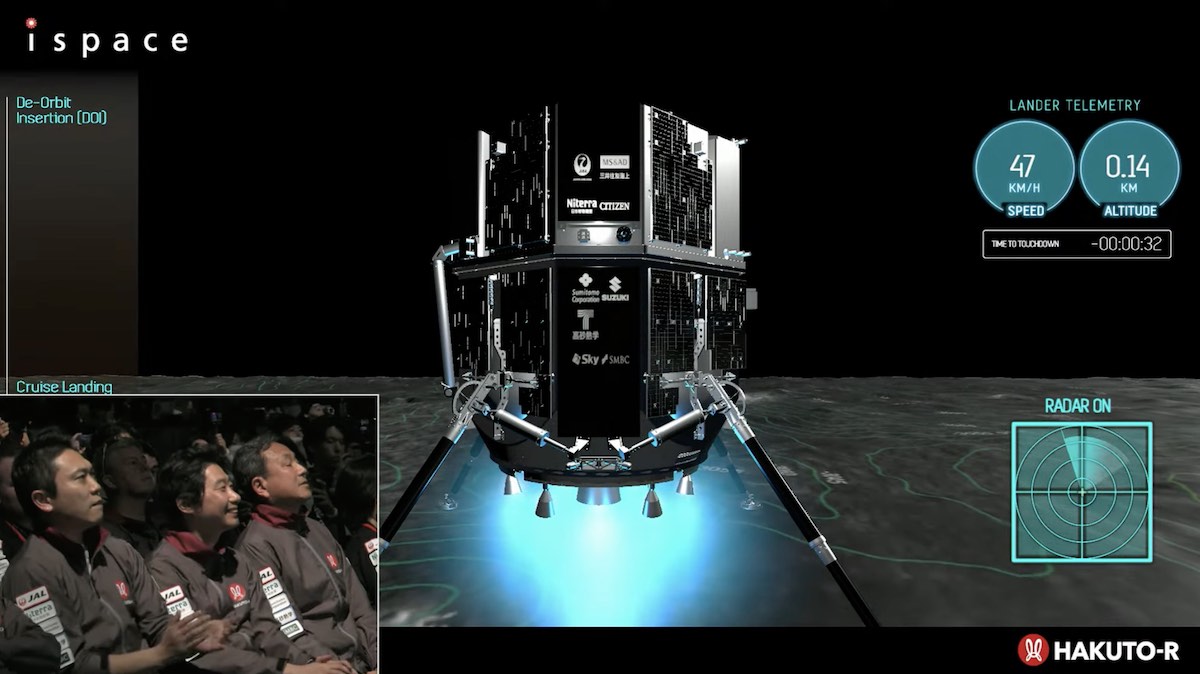

Scenes broadcast from ispace’s Tokyo control center showed nervous looks on the faces of engineers gathered to monitor telemetry from the spacecraft. Smiles and chatter among ispace executives turned into silent waiting as ground controllers stopped receiving the live data stream from the Hakuto-R lander, a car-size spacecraft that launched in December from Cape Canaveral on top of a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

Takeshi Hakamada, founder and CEO of ispace, said in remarks a few minutes after the landing attempt that ground teams received communication from the spacecraft until the “very end” of the descent sequence, but were unable to reestablish contact.

“So we have to assume that we could not complete the landing on the lunar surface,” Hakamada said.

A data display on ispace’s live webcast of the landing attempt appeared to show the last confirmed telemetry from the Hakuto-R spacecraft indicated the lander was at an altitude of 90 meters (295 feet) and descending at 33 kilometers per hour (20.5 mph). If successful, a landing would have made ispace the first company to safely put a privately-funded spacecraft on the surface of another planetary body.

In a statement later Tuesday, ispace reported that a successful landing was “not achievable.”

A preliminary analysis of data from the spacecraft indicated the estimated remaining propellant was “at the lower threshold,” then the lander’s descent speed rapidly increased, ispace said. If the spacecraft ran out of propellant, the lander’s engines would have shut off, causing it to fall to the surface.

“Based on this, it has been determined that there is a high probability that the lander eventually made a hard landing on the moon’s surface,” ispace said in a statement.

The company said its engineers are examining data to clarify details of the events that led to the loss of the mission.

Hakamada established the enterprise that became ispace in 2010. Following starts, stops, and wholesale changes in scope, ispace’s first moon landing mission — called Mission 1 — finally launched in December.

The original impetus for Hakamada’s company was the pursuit of the Google Lunar X Prize, the sweepstakes that offered a $20 million grand prize to the first privately-funded team to put a lander on the moon. Hakamada’s group, called Hakuto, worked on designing a lunar rover to ride to the moon on another lander. But the Google Lunar X Prize shut down in 2018 without a winner, leading some of the teams to dissolve or struggle to find new purpose.

Hakamada redirected ispace’s efforts to design and develop its own moon lander, a reboot the firm calls Hakuto-R. Hakuto means “white rabbit” in Japanese.

Despite the landing failure Tuesday, Hakamada said he is “very proud” of ispace’s team. The Japanese company has another lunar lander scheduled to launch on Mission 2 in 2024, and a Mission 3 using a larger spacecraft design is in the early stages of development for launch in 2025. Mission 3 will attempt to land on the far side of the moon, accompanied by two small communications relay satellites to enable contact between the lander and Earth.

Hakamada said ispace’s Mission 1, despite the crash landing, is a “great achievement” to provide experience and knowledge to feed into preparations for following mission. Engineers acquired “valuable data and know-how” throughout the Hakuto-R lander’s flight to the moon, up until the final moments of the landing sequence, according to ispace.

“We will keep going,” Hakamada said. “Never quit the lunar quest.”

The lunar landing attempt by ispace was the second time a privately-funded spacecraft has tried to land on the moon. The Israeli Beresheet mission, developed by a non-profit organization, crashed on the moon during a landing attempt in 2019.

Now boasting a staff of more than 200 employees, ispace has raised its funding through equity financing and bank loans. Hakamada’s investors include Suzuki, Japan Airlines, the Development Bank of Japan, Konica Minolta, Dentsu, and numerous venture capital and equity funds.

“For startup companies, the financing is really important,” said Jumpei Nozaki, chief financial officer of ispace. “We are very proud, and we are very fortunate that we could raise more than $300 million in money so far to support not only one single mission, but all three missions together.”

The company says it “specializes in designing and building lunar landers and rovers,” with an objective to “extend the sphere of human life into space and create a sustainable world by providing high-frequency, low-cost transportation services to the moon.”

“We have to assume that we could not complete the landing on the lunar surface,” says Takeshi Hakamada, founder & CEO of ispace.

Ground teams had data from the lander during its descent, but lost the signal before landing.

“We will keep going,” he said.https://t.co/3gIL8TclRe pic.twitter.com/Q5KVBwXjLZ

— Spaceflight Now (@SpaceflightNow) April 25, 2023

After launching in December, the Hakuto-R spacecraft took a longer but more fuel efficient route to the moon than the direct trajectory followed by NASA’s Apollo missions or the Orion spacecraft in the U.S.-led Artemis program. The Hakuto-R lander, which ispace calls its “Series 1” design, reached a distance of 855,000 miles (nearly 1.38 million miles) from Earth in February, becoming the farthest privately-funded, commercially-operated spacecraft in history.

The solar-powered spacecraft was then pulled back toward the moon by gravitational forces, and then Hakuto-R performed another engine burn March 21 to be captured into lunar orbit. Another 10-minute engine firing April 13 steered the spacecraft into a circular 60-mile-high orbit around the moon, setting up for the landing attempt Tuesday.

The lander’s propulsion system, provided by the European aerospace company ArianeGroup, consisted of a main engine to provide most of the thrust needed to slow for landing. There were six smaller “assist” thrusters clustered around the main engine, providing pulses for additional deceleration. Eight reaction control system thrusters provided pointing control for the the spacecraft.

The main engine ignited about an hour before the landing time for a braking maneuver to slow the spacecraft’s velocity enough to drop out of its orbit around the moon. Closer to the surface, the lander performed a pitch-up maneuver to point its main engine toward the moon, followed by a final descent phase to guide toward the landing site in Atlas crater.

According to ispace, data from the Hakuto-R lander indicated it was in the expected vertical orientation when ground controllers lost contact Tuesday. A few moments before landing, the main engine was supposed to switch off, allowing pulses from the six assist thrusters to control the spacecraft’s descent rate until it settled onto the lunar surface.

Shock absorbers on the spacecraft’s four landing would have helped cushion the final touchdown.

Guidance, navigation, and control software developed by Massachusetts-based Draper controlled the Hakuto-R spacecraft’s automated landing sequence. The lander’s solar panels were supplied by Colorado-based Sierra Space.

Assuming the landing was successful, the spacecraft was designed to operate for about 10 days on the surface, long enough to deploy the two mobile payloads from the United Arab Emirates and Japan. The stationary landing craft was designed to relay communications signals from the deployable payloads back to Earth. The mission would have ended when sun set on the landing site to begin the two-week-long lunar night.

The Hakuto-R lander carried about 24 pounds (11 kilograms) of customer payloads. By far, the largest of the payloads lost on the landing attempt was a rover from the United Arab Emirates developed by the Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Center. While the rover took up most of the Hakuto-R lander’s payload capacity, it was still small in stature, measuring just 21 inches by 21 inches (53-by-53 centimeters).

The UAE’s moon rover, named Rashid, weighed about 22 pounds (10 kilograms) in Earth’s gravity. The rover would have rolled off the Hakuto-R spacecraft a couple of days after landing, then surveyed the landing site with a pair of French cameras, and microscopic and thermal imagers to study rocks and soils. The rover had two Langmuir probes to measure the plasma environment at the moon, which can lift dust particles and transport them across the lunar surface.

Engineers also embedded small samples of different materials on the rover’s four wheels, part of a technology experiment to evaluate how well the materials withstand the abrasive rock and dust on the moon.

But with the crash landing Tuesday, the UAE’s lunar program will have to wait for a future opportunity to explore the moon.

Also lost on the Hakuto-R lander were a tiny mobile robot developed by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency and the Japanese toy company Tomy, a solid-state battery technology demonstration experiment, a 360-degree imaging system from Canadensys, an artificial intelligence flight computer from Mission Control Space Services, and a demonstration for NGC Aerospace’s crater-based autonomous navigation system.

Government-led missions from the United States, the Soviet Union, and China have landed on the moon, but so far, no commercial company has accomplished the great without government backing.

Aside from the payloads mounted on the lander, ispace aimed to fulfill a contract with NASA with the first Hakuto-R mission. NASA awarded contracts in 2020 to purchase lunar regolith from commercial companies, including a $5,000 deal to ispace. All of the agreements were relatively low in monetary value.

The initiative is part of NASA’s Artemis moon program. NASA wants to eventually contract with commercial companies to acquire resources, such as minerals and water, that could sustain a future moon base. The transfer of ownership of lunar soil from a private company to NASA will help officials on both sides of the transaction sort through legal and regulatory issues.

While ispace’s Mission 1 landing attempt was a purely commercial mission, ispace is working with Draper and other space companies to develop a larger robotic moon lander to transport up to a half-ton of cargo to the moon for NASA. Draper and ispace won a NASA Commercial Lunar Payload Services, or CLPS, contract last year to deliver multiple NASA science instruments to the moon’s surface in 2025 on ispace’s Mission 3.

NASA’s first two CLPS missions will be flown by Astrobotic and Intuitive Machines. Both of those companies plan to launch their first privately-developed moon landers later this year. The Peregrine lander from Pittsburgh-based Astrobotic will launch on the first flight of United Launch Alliance’s new Vulcan rocket, while the first Intuitive Machines mission, called IM-1, will send the company’s Nova-C lander to the moon on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

With ispace’s crash Tuesday, Astrobotic and Intuitive Machines now have a chance to make history as the first company to achieve a soft landing on the moon.

“We congratulate the ispace team on accomplishing a significant number of milestones on their way to today’s landing attempt,” Astrobitic tweeted. “We hope everyone recognizes today is not the day to shy away from pursuing the lunar frontier, but a chance to learn from adversity and push forward.”

“From the launch of Hakuto-R to the descent and approach to the moon’s surface, ispace has demonstrated its expertise in space exploration and its commitment to pushing the boundaries of what’s possible,” said Steve Altemus, president and CEO of Houston-based Intuitive Machines. “The technologies developed and tested by ispace continue to pave the way for future advancements in space exploration and cast a positive light on the emerging lunar economy.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.