The departure at dawn of a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket from Cape Canaveral Thursday sent aloft the U.S. military’s last Space Based Infrared System missile warning satellite, a $1.2 billion mission billed by the Space Force as a stepping stone to a new generation of more sensitive sentinels in the sky.

The Atlas 5 launched from pad 41 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station at 6:29 a.m. EDT (1029 GMT) Thursday to begin a three-hour ascent before releasing the SBIRS GEO 6 missile warning satellite into orbit.

Two strap-on solid rocket boosters from Northrop Grumman and a Russian-made RD-180 main engine powered the Atlas 5 off the launch pad with 1.6 million pounds of thrust. The 194-foot-tall (59-meter) rocket soared into sunlight as it reached the upper atmosphere, giving its exhaust plume an orange hue against the deep blue sky.

The Atlas 5 jettisoned its boosters about two minutes after liftoff, then shut down its kerosene-fueled RD-180 engine about four minutes into the mission. The rocket’s Centaur upper stage ignited its RL10 engine for the first of three burns to accelerate into a preliminary parking orbit. A payload shroud that protected the SBIRS GEO 6 satellite during the early phases of launch released like a clamshell during the first Centaur burn.

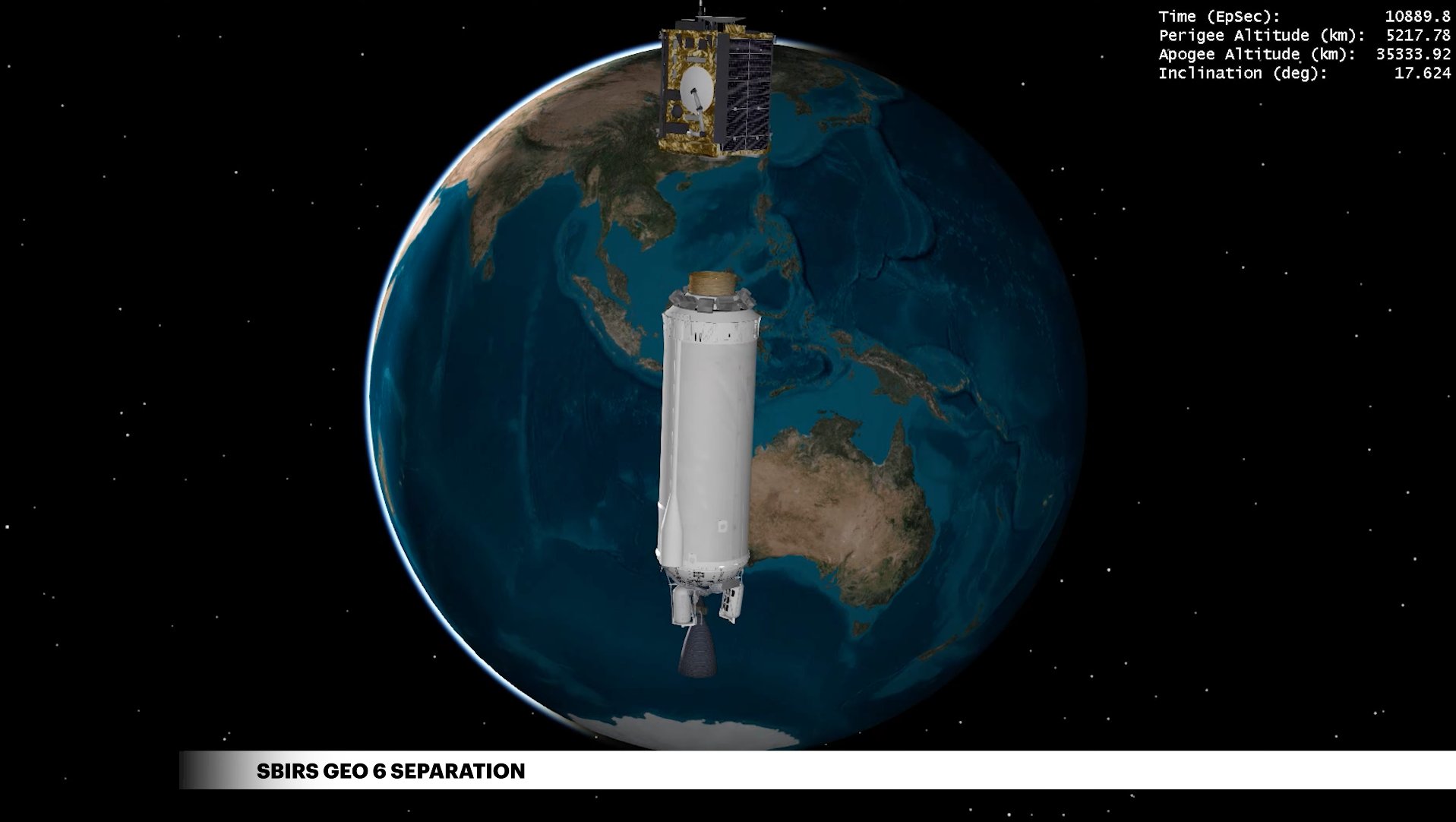

Two more firings by the Aerojet Rocketdyne RL10 upper stage engine guided the Space Force payload into an elliptical, or oval-shaped transfer orbit. The Atlas 5’s guidance computer targeted an orbit ranging in altitude between 3,242 miles (5,218 kilometers) and 21,956 miles (35,335 kilometers), with an inclination angle of 17.63 degrees to the equator.

ULA confirmed a good separation of the SBIRS GEO 6 satellite around 9:30 a.m. EDT (1330 GMT), roughly three hours after liftoff, completing the 95th flight of an Atlas 5 rocket and the fifth Atlas 5 launch of the year.

Here’s our triple camera replay of the launch of ULA’s Atlas 5 rocket from Cape Canaveral at 6:29am EDT (1029 GMT), carrying the US Space Force’s sixth SBIRS missile warning satellite into orbit. https://t.co/OUQYolLhnp pic.twitter.com/W1bss5gtqN

— Spaceflight Now (@SpaceflightNow) August 4, 2022

“SBIRS GEO 6’s successful launch is a great achievement for the entire team and nation,” said Col. Brian Denaro, program executive officer for space sensing at Space Systems Command. “Our near-peer competitors continue to develop missile technology that is faster-burning and dimmer, as well as harder to detect. The U.S. Space Force’s SBIRS constellation provides the world’s most advanced capability to detect missile launches earlier and track these threats more accurately.”

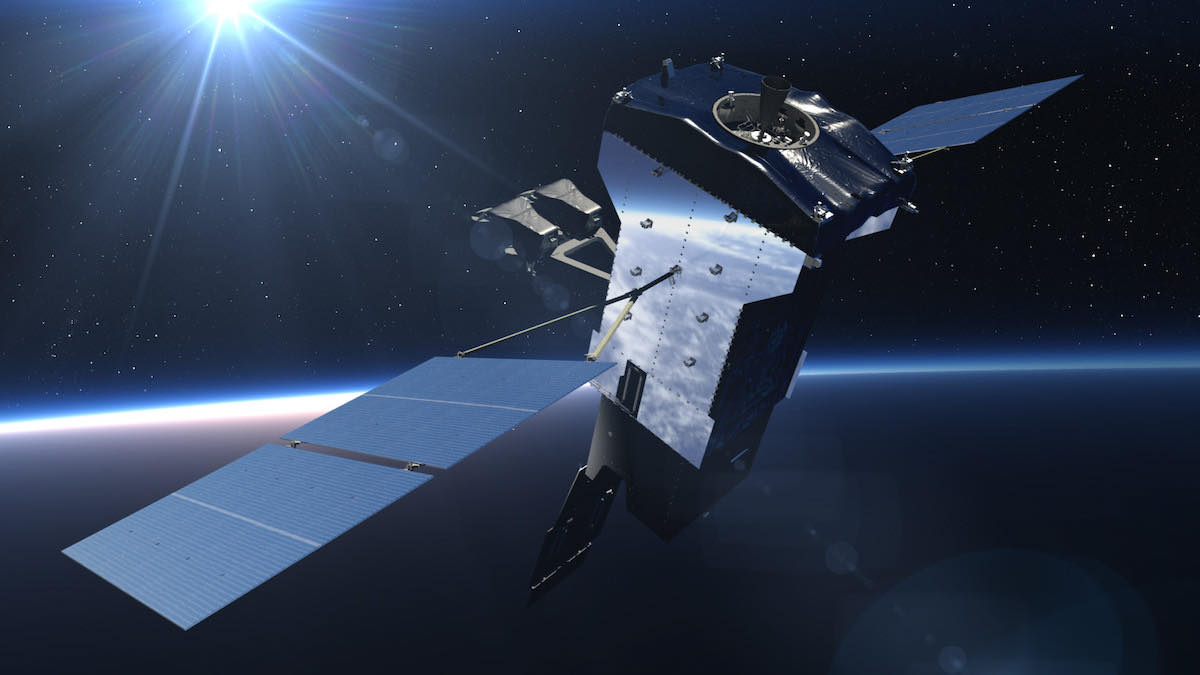

The SBIRS GEO 6 satellite, built by Lockheed Martin, will use on-board propulsion to maneuver into a circular geosynchronous orbit more than 22,000 miles (nearly 36,000 kilometers) over the equator. In that orbit, the spacecraft will have a fixed geographic coverage zone as it circles Earth at the same rate of the planet’s rotation.

Once the new satellite is operational next year, the Space Force’s SBIRS fleet will have six spacecraft operational in geosynchronous orbit, providing global infrared coverage to detect the heat plumes from missile launches. There are also SBIRS infrared payloads hosted on classified spy satellites in highly elliptical orbits with coverage over the North Pole, and the military continues operating older Defense Support Program missile warning satellites, which the SBIRS program replaced.

The SBIRS and DSP satellites provide the first warning of a missile launch that could be aimed at the U.S. homeland, allied nations, or deployed military forces.

“As the space domain has transitioned from a benign to a contested and congested environment, SBIRS GEO 6 provides another critical unblinking eye to detect, track and defend against ballistic and hypersonic missile threats, improving data gathering and battlespace awareness capabilities,” Denaro said in a conference call with reporters before the launch of SBIRS GEO 6. “This mission advances our capacity to detect missile launches earlier and track these targets more accurately.”

Northrop Grumman supplied the infrared sensors on each SBIRS satellite.

One of the infrared cameras on each SBIRS GEO satellite scans across the spacecraft’s coverage area in a U-shaped pattern. Another infrared sensor can be aimed at specific regions of interest.

“There’s a staring sensor that can be pointed at and stare at a fixed point,” said Michael Corriea, Lockheed Martin’s vice president overseeing the SBIRS program. “So for example, you can task it to look over China because there was something you maybe wanted to look at in a particular area, or North Korea.

“Both sensors are infrared sensors, so they detect the heat signature of the rocket, not only just the initial heat from the rocket launch, but also as the rockets go through the atmosphere, they get heated up and warmed and we can check them through that heat signature as well,” Corriea said.

“SBIRS GEO 6, as well as the other SBIRS satellites, basically has four missions,” Corriea said. “The first is missile warning. It’s got scanning and staring sensors that can see the Earth and detect a launch and then, using some algorithms, determine where that missile is going to land. So it’s able to do the missile detection and warning, and then inform the decision makers or people in the United States about an incoming attack to take appropriate actions.”

The first SBIRS payload in an elliptical orbit launched in 2006, and the military launched the first SBIRS satellite into geosynchronous orbit in 2011. The military launched 23 older design DSP missile warning satellites between 1970 and 2007.

The SBIRS satellites also provide data for intelligence analysts and military forces.

“As Russia and China and other nations build and test new missiles, the data from the (SBIRS) sensors can be collected on those new missiles and the intelligence community can do an analysis about what those missiles are, what their capabilities are, or how they work,” Corriea said. “And then the fourth and final portion of the SBIRS mission is it really helps with battlespace awareness. The cameras are sensitive enough to be able to take a look at the battlefield. That data can be provided to operators in the field, so that they can understand what’s going on and have improved awareness of the battlefield.”

The infrared sensitivity provided by the SBIRS satellites can also detect the thermal signature from objects as they re-enter the atmosphere and burn up. SBIRS infrared data has also been useful in detecting and locating wildfires.

The SBIRS GEO 6 satellite was built at Lockheed Martin’s manufacturing and test facility in Sunnyvale, California, and delivered to Cape Canaveral earlier this year for launch preparations. Once filled with maneuvering propellant for orbit-raising and station-keeping, the spacecraft weighed about 10,700 pounds (4,850 kilograms) in launch configuration.

With the Space Force’s fleet soon to have six SBIRS satellites in geosynchronous orbit, plus an unspecified number of aging DSP satellites, officials said the missile warning network is in good shape until a new generation of infrared sensing platforms is ready for launch.

With overlapping coverage around the world, multiple SBIRS or DSP satellites can often detect and track a missile, giving military operators a better of idea if its trajectory.

“We have satellites that are up there, and when it’s absolutely optimized is when we have stereo coverage, in other words there’s overlapping coverage,” said Col. Daniel Walter, senior materiel leader for Space Systems Command’s strategic missile warning acquisition program. “When you get multiple looks at a single launch, it really helps with the accuracy and assuredness of (tracking) that launch.”

Lockheed Martin is building three Next-Generation Overhead Persistent Infrared, or OPIR, satellites to be positioned in geosynchronous orbit. The OPIR spacecraft for geosynchronous orbit will be built on the same platform as the SBIRS GEO 5 and 6 satellites, but will fly with upgraded infrared sensors. The first of the next-generation geosynchronous satellites is scheduled for launch in the second half of 2025, Corriea said.

The Space Force has contracted with Northrop Grumman to build two OPIR satellites to launch into highly elliptical polar orbits to provide missile warning coverage over the North Pole.

The SBIRS GEO 6 mission was the ninth and final flight of an Atlas 5 rocket in the “421” vehicle configuration, with two strap-on solid-fueled boosters and a conical 4-meter (13-foot) diameter payload fairing. ULA is phasing out the Atlas 5 rocket and the Delta 4 rocket family. Both rockets will be replaced by the new Vulcan Centaur launcher, which ULA says is less expensive and more capable than the Atlas and Delta rocket fleets.

The Vulcan Centaur will also be powered by U.S.-made main engines produced by Blue Origin, replacing the Russian RD-180 on the Atlas 5. There are 21 Atlas 5 missions left on ULA’s launch backlog after the launch of SBIRS GEO 6. ULA say all of the RD-180 engines required for the remaining Atlas 5 flights have been delivered to the United States from Russia.

All but one of the remaining Atlas 5 missions will fly with a larger version of the payload fairing.

ULA’s next launch is scheduled to take off from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California, where a Delta 4-Heavy rocket will send a U.S. government spy satellite into orbit. The next Atlas 5 launch is scheduled for late September from Cape Canaveral with a pair of commercial communications satellites for SES.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.