SpaceX plans to transform parts of NASA’s Kennedy Space Center to become an operational base for the company’s super-powerful Starship launcher, while keeping a sprawling complex in South Texas as a research and development location for the heavy-lift rocket program, Elon Musk said Thursday.

Musk, the founder and chief executive of SpaceX, said in December that SpaceX had started construction of an orbital launch site for the Starship on Launch Complex 39A at Kennedy Space Center, but his comments Thursday suggested the company has carved out long-term roles for the government-owned Florida spaceport and the privately-run test site in Cameron County, Texas, also known as Starbase.

“The future role of Starbase, I think it’s well-suited to be our advanced R&D location,” Musk said. “So it’s like where we will try out new designs and new versions of the rocket, and I think probably … Kennedy will be our sort of main operational launch site.”

Under such a plan, SpaceX would have teams at two locations building Starships. After rapidly expanding its factory footprint in Texas over the last few years, SpaceX is planning to construct a rocket production facility inside the gates of Kennedy Space Center.

SpaceX currently operates two launch pads at Cape Canaveral for its Falcon rockets.

At pad 39A, once home to NASA’s Saturn 5 moon rocket and space shuttle launches, SpaceX launches astronaut crews to the International Space Station and Falcon Heavy rockets, made by combining three Falcon rocket cores together to generate some 5.1 million pounds of thrust, more than any other operational launcher in the world.

The Starship dwarfs all of those rockets, with the ability to haul up to 100 tons of cargo into a “usable” orbit a few hundred miles above Earth, Musk said.

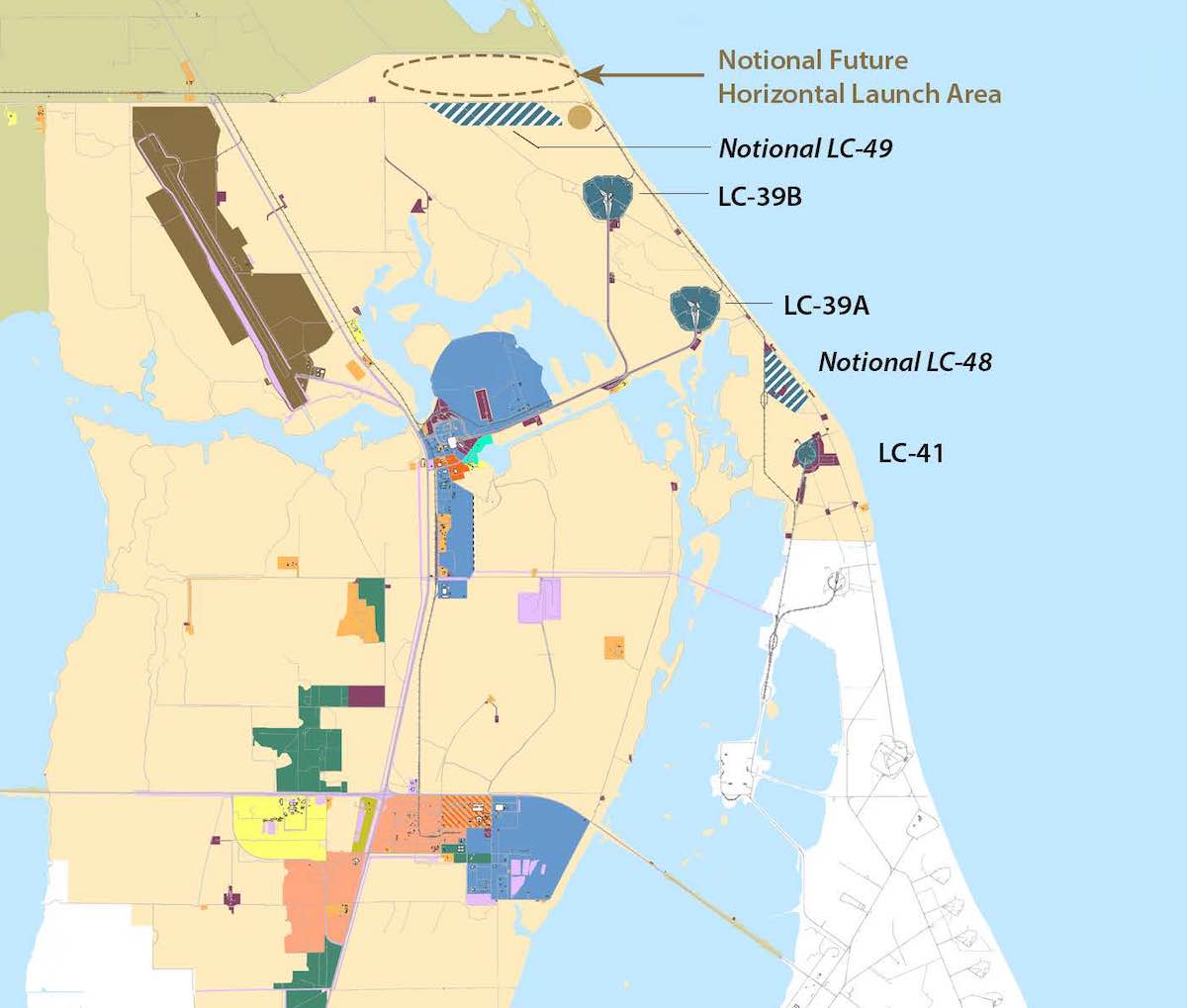

SpaceX is building a Starship pad just southeast of the Falcon rocket’s launch mount within the fenced-in perimeter of pad 39A, which officials hope to complete later this year. The company is also interested in developing another Starship launch pad, known as Launch Complex 49, a few miles to the north.

Musk presented an update on the huge Starship rocket program Thursday, standing in front of a towering fully-stacked Starship rocket, the tallest launch vehicle and most powerful ever built. SpaceX did not say whether the rocket used as a backdrop Thursday, which was once intended to blast off on the first Starship orbital launch attempt, is still expected to actually fly.

But other Starships are in production a few miles away at the Starbase factory.

“We are talking about a rocket that’s more than twice the mass and thrust of a Saturn 5 (used on NASA’s Apollo moon program), and also designed to be fully reusable,” Musk said. “And obviously it’s much better from an environmental standpoint to have a reusable rocket.”

SpaceX aims to complete the Starship at a development cost of between 5% and 10% that of the Saturn 5 in the 1960s, Musk said.

“Of course, we need to make it work,” Musk said. “It hasn’t worked yet. It will work. There might be a few bumps along the road, but it will work”

He said he was optimistic the nearly 400-foot-tall (120-meter) rocket will launch on a test flight into Earth orbit before the end of the year. Ground crews at the test facility near Boca Chica Beach east of Brownsville are racing to complete work on a series of Starship vehicles, Super Heavy boosters, and a towering launch pad just inland from the Gulf of Mexico.

“I feel, at this point, highly confident that we’ll get to orbit this year,” Musk said. “We’re making a lot of rockets, making a lot of engines.”

Musk’s update Thursday night was the first detailed presentation on the Starship program since September 2019. Much has changed since then, with five test flights of full-scale Starship prototypes in the books. The test flights focused on working out how to land the Starship, which comprises the upper portion of the overall rocket.

The first four Starship atmospheric test flights all ended in explosions, before the fifth test resulted in a successful landing last May. SpaceX’s attention in recent months has switched to building out the huge Starship launch pad tower.

Overnight Wednesday into Thursday, SpaceX teams stacked a Starship test vehicle on top of a Super Heavy rocket, creating a dramatic scene for Musk’s presentation Thursday night.

The privately-funded rocket, made of shiny stainless steel, will be the most powerful to ever fly. Future versions of the Super heavy will have 33 methane-fueled Raptor engines producing some 17 million pounds of thrust at liftoff. It’s also designed to be fully reusable, with the Super Heavy booster and Starship — essentially part upper stage and part in-space transporter — capable of returning to Earth with a vertical landing back on its launch pad, and then flying again.

The Starship itself will have six Raptor engines initially, but that could grow to nine engines — three designed for landing propulsion on Earth, and six for use in the vacuum of space.

The Starship’s first orbital test flight, though audacious in scale, will aim to prove out the rocket’s basic launch and re-entry capabilities without fully testing out the complicated landing and recovery systems, according to a SpaceX filing with the Federal Communications Commission last year.

On the first orbital mission, SpaceX plans for the Starship to re-enter the atmosphere after one trip around Earth, heading for a controlled landing at sea in the Pacific Ocean near Hawaii. The Super Heavy booster will splash down in the Gulf of Mexico.

Since Musk’s last Starship presentation two-and-a-half years ago, SpaceX has also won a contract with NASA to develop the Starship into a human-rated lander for the agency’s Artemis moon missions. A moon derivative of the Starship, assisted by Starship refueling tankers, will be utilized for a lunar landing with astronauts, an event NASA says could happen no earlier than 2025.

NASA, meanwhile, is in the final stages of readying its government-owned heavy-lifter called the Space Launch System at Kennedy Space Center. It’s scheduled to launch for the first time this spring with an Orion crew capsule on an unpiloted Artemis test flight to lunar orbit and back to Earth.

The U.S. space agency plans to use the SLS and Orion as a transportation system for astronauts traveling between Earth and the moon. The Starship, and eventually more commercial lunar landers, will meet up with the Orion capsule near the moon to ferry crews to and from the lunar surface.

While engineers plow toward the Starship’s first orbital test flight, SpaceX is also awaiting the conclusions of an environmental review by the Federal Aviation Administration before regulators give the green light for Starship launch operations at the South Texas site.

The FAA issued a draft environmental report in September after consultation with several federal and state agencies, then held two virtual meetings in October to collect input from the public. The FAA said in December that volume of public comments would cause the agency to miss its goal to complete the environmental review by the end of December. Officials shifted the timetable to the end of February, but that self-imposed deadline is now in doubt.

“I think we’re close to having the hardware ready to go,” Musk said. “Right now, I think we’re tracking to have the regulatory approval and hardware readiness around the same time … hopefully in basically a couple months for both.”

The review marks a re-evaluation of the FAA’s original environmental impact statement before SpaceX started construction of the Boca Chica site in 2014. At that time, SpaceX planned to launch Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets from South Texas, but the scope of the project has since changed to focus on development of Starship and Super Heavy.

The FAA is deciding whether to finalize the draft environmental assessment completed last year if regulators find Starship launch operations will not have a significant impact on the local environment. The agency could also decide to begin a new environmental impact statement if the environmental effects would be significant and could not be properly mitigated.

A new environmental impact statement would take months, or even years, to complete.

The development of a Starship launch site and factory at Kennedy Space Center is not only SpaceX’s insurance policy against delays caused by regulatory scrutiny. Musk said Thursday the Florida facility will serve as an operational base for Starship missions, while the Texas location is a better fit for testing.

“I am optimistic that we will get approval (from the FAA),” Musk said. “Objectively, I think this is not something that will be harmful to the environment. We’ve obviously flown the ship several times, and multiple landings, takeoffs and landings. We’ve fired the engines a lot. I think the reality is that it would not have a significant impact.”

“That doesn’t mean things don’t get delayed from a regulatory standpoint,” Musk continued. “We are in a litigious society, so there’s always lawsuits from someone. It’s lawsuit city.”

Musk said an FAA decision to require a new environmental impact statement would “set us back for quite some time,” requiring SpaceX to immediately shift more research and development work to Kennedy Space Center. He said SpaceX’s “worst case scenario” would be a delay of six to eight months, which Musk claimed would be enough time to build up a Starship launch tower at Kennedy Space Center.

The FAA said it is reviewing the environmental impacts from SpaceX’s Starship launch and re-entry operations, debris recovery, the launch pad integration tower and other launch-related construction, and local road closures at Boca Chica.

SpaceX can’t launch the Starship and Super Heavy vehicle until the FAA issues a license, which will only come after the completion of the environmental process.

SpaceX already has passed an environmental review for Starship launches from Launch Complex 39A. It would need to go through a new process at Launch Complex 49.

The company originally selected the Boca Chica Beach location for a Starship production and test site to avoid interfering with Falcon missions launching out of Florida.

“It’s basically here and Cape Canaveral are the two possibilities,” Musk said, referring to near-term Starship operations. “Because we had a lot of launches going out of the Cape, we didn’t want to disrupt the Cape activity … So we just wanted to decouple the operational launches from the R&D launches, and thats why we’re at this location.”

Musk also outlined technology challenges facing the Starship program. One topic he discussed at length Thursday night was the production and testing of a new version of the Raptor engine, called the Raptor 2, needed to power future Starship launches.

The uprated engine can produces at least 460,000 pounds of thrust, 25 percent more power than the original Raptor engine design. Musk said the Raptor 2 could be tuned to generate 500,000 pounds of thrust. It burns the same propellant mix of methane and liquid oxygen, but uses fewer parts and is cheaper and easier to manufacture, making it crucial for realizing SpaceX’s lofty cost and performance goals for the Starship program.

Testing of the Raptor 2 engine is moving the powerplant closer to being flight-ready, but engineers are still working to resolve technical issues with the engine.

Musk first discussed the Starship program in 2016, several years after technical work began on the project. Then known as an interplanetary transport system, the rocket has undergone countless design changes since 2016.

But the end goal has remained constant: Develop and fly a fully reusable rocket that can carry more cargo into space than any launcher in history, and then use it to establish a settlement on Mars.

“I think, maybe, roughly, you need about a million tons on Mars to have a self-sustaining city,” Musk said. “Starship is capable of doing that. It’s capable of getting a million tons to the surface of Mars and creating a self sustaining city, and I think we should try to do that is as soon as we can.”

Pulling off a Mars mission, and then establishing a repeatable cadence of sorties to the Red Planet, will require numerous launches of Starship tankers, cargo and crew transporters, and propellant depots.

Elon Musk says SpaceX’s Starship will be capable of creating a self-sustaining city on Mars, a goal he says will require the delivery of roughly a million tons of cargo and equipment. https://t.co/g9Pu7ohxAd pic.twitter.com/J8HlhXJbwJ

— Spaceflight Now (@SpaceflightNow) February 11, 2022

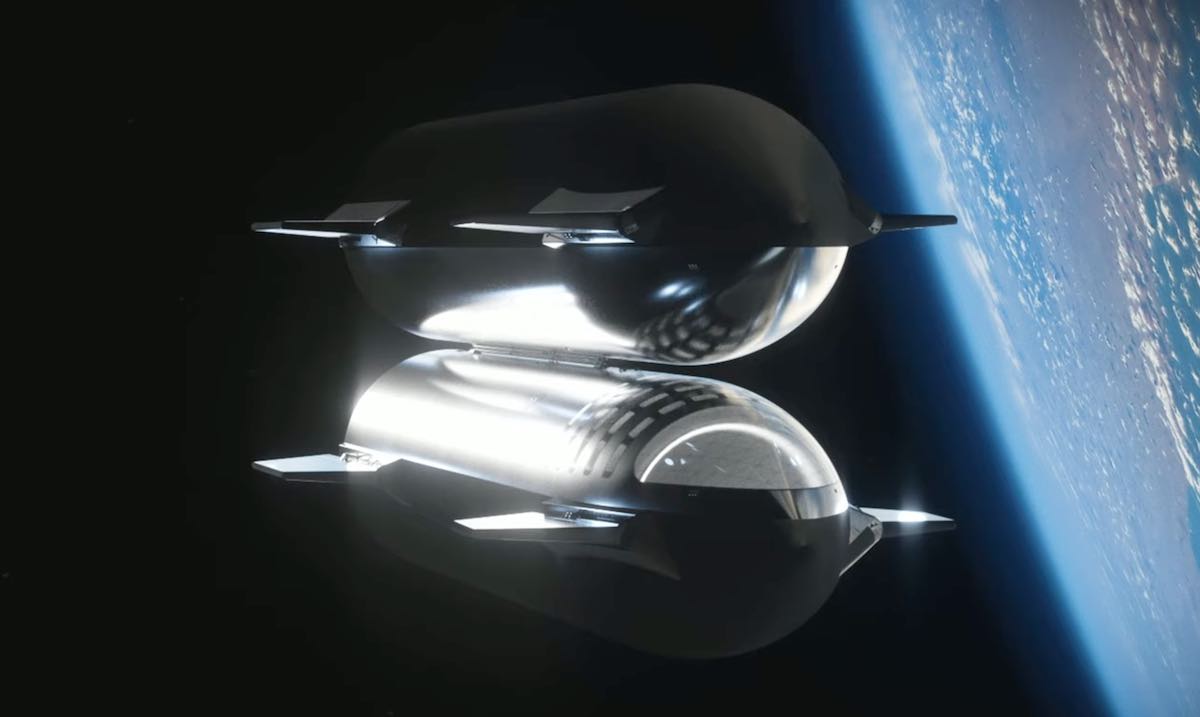

SpaceX eventually wants to have Starship variants designed to refill deep space transporters with methane and liquid oxygen propellants in Earth orbit. That capability could be tested in Earth orbit by the end of next year, Musk said. In-orbit cryogenic refilling is a prerequisite for using a Starship vehicle to land astronauts on the moon for NASA’s Artemis program.

The Starship launch complex at pad 39A could be used in NASA’s Artemis lunar campaign. Getting the Starship lander to the moon will require multiple orbital refilling missions using a tanker variant of the Starship vehicle.

The rapid-fire launch campaign for an Artemis lunar landing mission may require SpaceX to use multiple launch pads. NASA’s SLS moon rocket will launch from pad 39B, another Apollo-era launch facility located less than 1.7 miles (2.7 kilometers) north of pad 39A.

Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa announced in 2018 he plans to fly around the moon on a Starship in 2023. Last year, he said he wanted to take eight members of the public with him on the journey. A launch schedule for Maezawa’s flight has not been updated recently, but is not likely to happen next year.

Other versions of the Starship could be designed with a cargo bay to deploy satellites, either huge spacecraft like an astronomical telescope, or hundreds of smaller satellites, such as those used for SpaceX’s own Starlink internet service.

And SpaceX has toyed with the idea of using Starship as a point-to-point transporter for cargo and people traveling from one side of Earth to another. The U.S. Air Force said last year it awarded SpaceX a contract to study using the Starship as an intercontinental ferry for military cargo.

Musk provided few details about the potential uses for the Starship rocket, beyond Mars and lunar flights. But he projected that within a few years Starship missions could launch for less than $10 million per flight, accounting for marginal costs like propellant and the overhead of running the program.

“This design, I’m confident, is capable of that,” Musk said. “It’s just a question of how long it will take to refine that and have it really dialed.”

Once the Starship program is humming along at an operational cadence — which could mean multiple flights per day if Musk’s vision is realized — SpaceX plans to field ocean-going launch pads to accommodate the volume of flights far away from cities and towns.

SpaceX has two former oil rigs it intends to convert into floating launch pads. That work was “de-prioritized” over the last year as SpaceX emphasized progress in Texas, Musk said, but one of the platforms could be fitted with a “catch tower” to receive landing booster rockets later the year.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.