In a pair of mission extensions, NASA has cleared the way for more seismic observations on Mars with the robotic InSight lander and approved plans for the Juno spacecraft to alter its orbit and perform close flybys of Jupiter’s icy moon Europa, Ganymede, and the volcanic moon Io.

The Juno mission, in orbit around Jupiter since July 4, 2016, has been approved for a four-year extension through September 2025, assuming the spacecraft is still operating. NASA also granted a two-year extension for the InSight mission, which landed on Mars on Nov. 26, 2018.

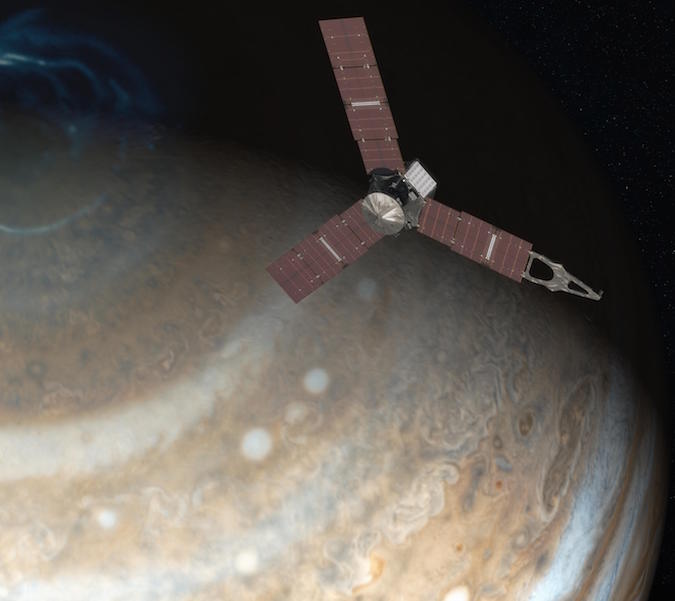

The Juno orbiter has focused on observations of Jupiter in its first four years at the giant planet, but the mission’s task list will grow in the coming years to include flybys and measurements of Jupiter’s rings and three of its largest moons.

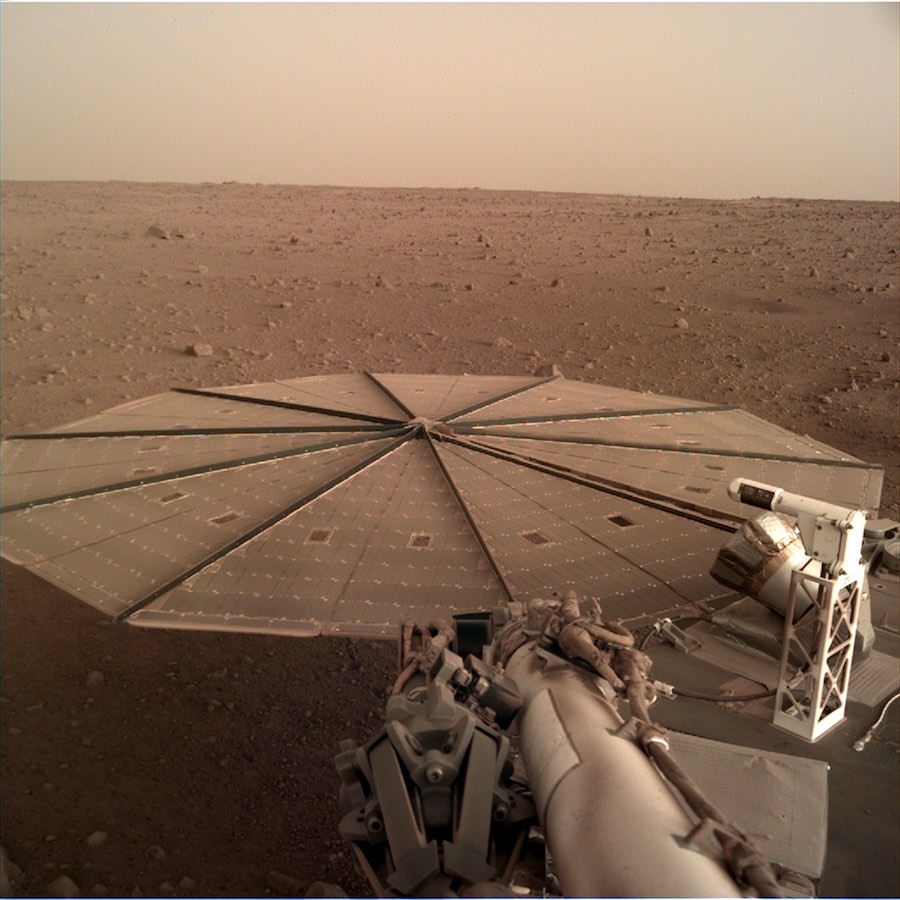

Led by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the InSight mission has been extended two years through December 2022. InSight will continue measuring seismic tremors on the Mars, producing data to help scientists unravel the internal structure of the Red Planet.

The solar-powered Mars lander will also continue operating a weather station, and ground teams will develop plans to bury a tether leading to InSight’s seismometer in hopes of eliminating data dropouts from the instrument.

A lower priority for the InSight team in the two-year extended mission will be to continue efforts using the lander’s robotic arm to help a heat probe hammer itself deeper into the Martian soil. The mole — one of InSight’s two main instruments alongside the seismometer — stalled in early 2019 before reaching a planned depth of at least 10 feet (3 meters) to measure the heat gradient inside the Red Planet.

Despite the problem with the heat probe, InSight’s seismic sensors have worked as designed. The seismometer instrument made the first detection of a “marsquake” soon after its deployment on the planet’s surface in 2019.

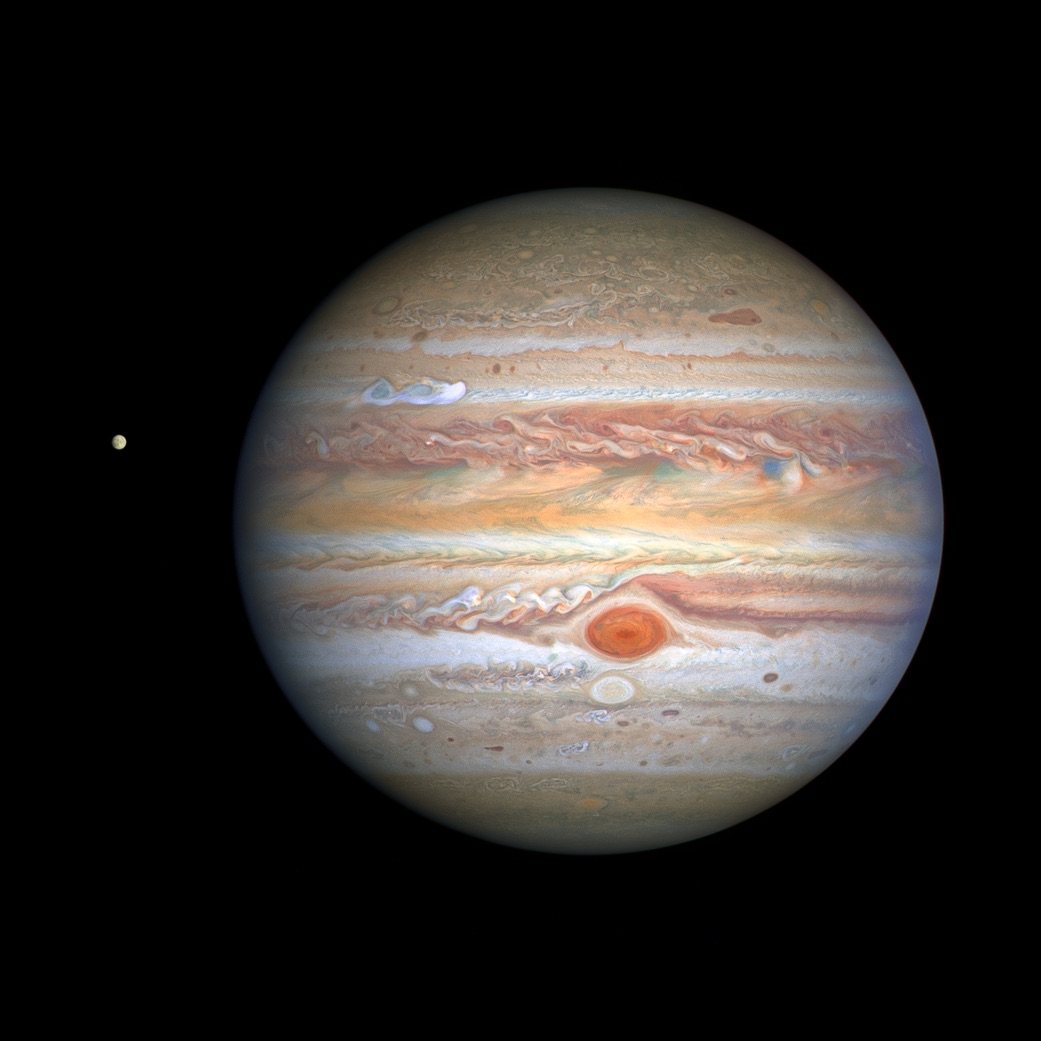

The Juno spacecraft has probed the Jupiter’s atmosphere and internal structure, revealing new insights about Jupiter’s cyclonic storms and detecting evidence for a large, potentially dissolved core at its center.

Scott Bolton, Juno’s principal investigator at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, said last year that the spacecraft could address a broader scope of science questions if NASA granted an extended mission.

“It really becomes a full system explorer, not as focused as the prime mission was,” Bolton said last year. “We have multiple flybys of Io, Europa and Ganymede.”

The solar-powered Juno spacecraft launched in August 2011, beginning a five-year cruise to Jupiter.

Juno’s nine scientific instruments include a microwave radiometer for atmospheric soundings, ultraviolet and infrared spectrometers, particle detectors, a magnetometer, and a radio and plasma waves experiment. The Jupiter orbiter also carries a color camera known as JunoCam, which collects image data for processing and analysis by an army of citizen scientists around the world.

NASA approved the extensions for the InSight and Juno missions after recommendations from a senior review, where a panel of independent scientists rank the merits of continuing to operate NASA’s robotic science missions beyond their original planned lifetimes.

When considering the senior review recommendations, NASA balances the scientific productivity of older missions with priorities to develop and launch new spacecraft. In 2020, InSight and Juno were up for extensions after reaching the end of their primary mission phases.

“The senior review has validated that these two planetary science missions are likely to continue to bring new discoveries, and produce new questions about our solar system,” said Lori Glaze, director of the planetary science division at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “I thank the members of the senior review panel for their comprehensive analysis and thank the mission teams as well, who will now continue to provide exciting opportunities to refine our understanding of the dynamic science of Jupiter and Mars.”

Juno’s primary mission cost around $1.1 billion, while InSight was developed, launched, and flown to Mars for about $1 billion, including contributions from European partners. The cost per year of operating each mission is significantly less than the cost of developing and launching the spacecraft.

The senior review panelists found InSight and Juno have “produced exceptional science” and recommended extending both missions. NASA approved the extensions Friday.

Lockheed Martin built the InSight and Juno spacecraft for NASA.

While InSight’s extension is largely about improving and extending datasets from the lander’s prime mission, Juno will take aim on new targets over the next four years.

The flybys of Jupiter’s moons will be enabled by Juno’s changing orbit. Jupiter’s asymmetric gravity field is gradually perturbing Juno’s trajectory and pulling the closest point of the spacecraft’s elliptical, or egg-shaped, 53-day orbit northward over time, according to Bolton.

The northward migration of Juno’s perijove, or closest approach to Jupiter, will allow the spacecraft to get a closer look at the planet’s north pole. Juno was the first mission to glimpse Jupiter’s poles, and now the spacecraft could see the north pole and its cyclonic storms in greater detail.

“This gives us close proximity to the northern parts of Jupiter, which is a new frontier,” Bolton said. “We’ve seen a lot of activity there, so we’ll be able to explore it very close up, whereas in the primary mission we were limited to the lower latitudes.”

In an extended mission, the spacecraft will also be able to quantify how much water is bound up within Jupiter’s atmosphere, Bolton said.

Juno’s naturally evolving orbit is also what will permit the spacecraft to pass near Jupiter’s moons and rings.

The moon flybys could begin in mid-2021 with an encounter with Ganymede, Jupiter’s largest moon, at a distance of roughly 600 miles (1,000 kilometers), Bolton said last year.

After a series of distant passes, Juno will swoop just 200 miles (320 kilometers) above Europa in late 2022 for a high-speed flyby. Only NASA’s Galileo spacecraft, which ended its mission in 2003, has come closer to Europa.

There are two encounters with Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io planned in 2024 at distances of about 900 miles (1,500 kilometers), according to the flight plan presented by Bolton last year. Juno will be able to look for changes on the surfaces of Jupiter’s moons since they were last seen up close by NASA’s Voyager and Galileo probes.

At Ganymede, Juno will map the moon’s surface composition and investigate the 3D structure of Ganymede’s magnetosphere. Ganymede is the only moon in the solar system known to have its own magnetic field.

Juno’s microwave radiometer will be able to probe the thickness of Europa’s global ice shell, which covers an ocean of liquid water. “We’ll see where the ice is thin and where it’s thick,” Bolton said.

Juno’s spectrometers will also map concentrations of water ice, carbon dioxide and organic molecules across 40 percent of Europa’s surface, Bolton said.

“Imaging observations will search for changes since Voyager and Galileo, and observations with the spacecraft’s microwave radiometer will explore Europa’s ice shell,” NASA said. “In situ measurements of Jupiter’s ring system will explore their structure and characterize their dust population.”

The visit to Europa would give scientists a taste of what’s to come with NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, which could launch as soon as 2024. Europa Clipper will carry a more powerful radar — among other instruments — to measure the moon’s ice shell through a series of targeted flybys.

The JunoCam imager will take the sharpest pictures of Europa since the Galileo mission’s last encounter with the icy moon in 2000, allowing scientists to search for evidence of plumes erupting from Europa’s surface.

The spacecraft’s other instruments will be tuned to look for particles lofted from Europa in the possible plumes. Signs of recurring eruptions from Europa were detected by the Hubble Space Telescope.

During its flybys with Io, Juno will look for evidence of a global magma ocean feeding Io’s volcanoes. Juno might also be able to observe active volcanoes in Io’s polar regions.

Juno is the second spacecraft to orbit Jupiter after the Galileo mission, which intentionally crashed into the giant planet in 2003. Galileo’s last close-up flyby of one of Jupiter’s moons, Io, occurred in 2002.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.