The announcement Monday of the discovery of phosphine gas in the clouds of Venus — an indicator of possible life — has raised hopes among scientists for new robotic missions to renew exploration of Earth’s planetary neighbor.

If Rocket Lab founder Peter Beck gets his way, a privately-funded mission could get the next crack at probing Venus’s soupy atmosphere. NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine also tweeted Monday: “It’s time to prioritize Venus.”

“Life on Venus? The discovery of phosphine, a byproduct of anaerobic biology, is the most significant development yet in building the case for life off Earth,” Bridenstine wrote.

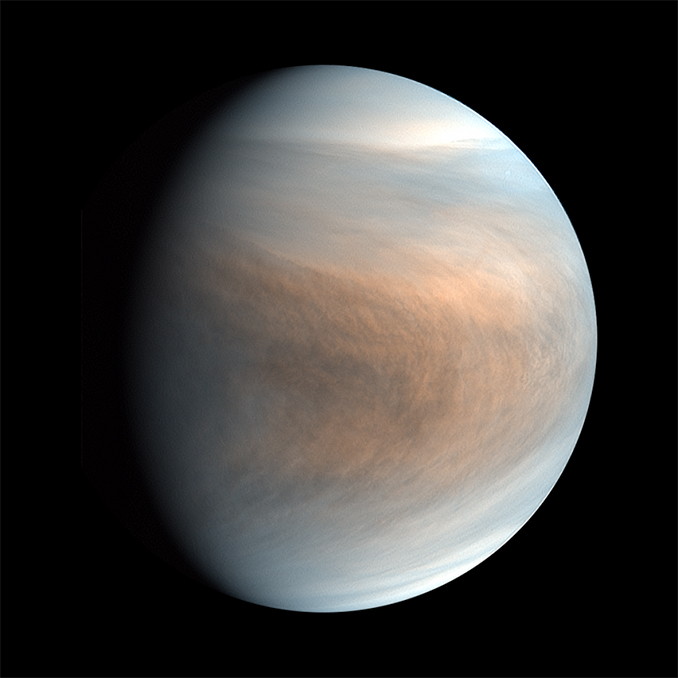

Venus is home to a hellish landscape that lies at the bottom of an opaque atmosphere made of carbon dioxide, with scorching surface temperatures as hot as 880 degrees Fahrenheit (471 degrees Celsius). Sometimes called Earth’s “evil twin,” it’s the closest world to our own.

At Venus’s scalding surface, the atmosphere is 90 times thicker than Earth’s, similar to the crushing pressure you would find 3,000 feet (900 meters) under the ocean. That doesn’t seem like an environment ripe for life.

But scientists have suggested simple life forms could take refuge high in Venus’s atmosphere, where temperatures and pressures are similar to conditions found at sea level on Earth. Astronomers announced Monday that observations through ground-based telescopes detected phosphine in Venus’s clouds.

Phosphine, made by combining a phosphorus atom with three hydrogen atoms, is only generated on Earth from microbes and industrial activity, scientists said. While a sliver of Venus’s atmosphere has the right temperature and pressure to harbor life, the region strewn with droplets of sulfuric acid and lacks water.

“The real challenge is seeing whether any form of life could evolve to adapt to the incredibly acidic environment,” said Jane Greaves, a professor at Cardiff University in the United Kingdom who led the team that discovered the phosphine signature, in an interview with Astronomy Now. “We just have no analogy (to those conditions) on Earth.”

Scientists have also struggled to come up with how other types of chemical reactions might produce phosphine at Venus, and the ambiguity led Greaves and her team to conclude the discovery could point to “aerial” life forms suspended in the atmosphere.

There’s one spacecraft currently flying around Venus — Japan’s Akatsuki orbiter — but its just the second orbiter sent on a dedicated mission to Venus in 30 years. The European Venus Express mission operated in orbit around the planet from 2006 through 2014.

Both missions have primarily observed the atmosphere of Venus.

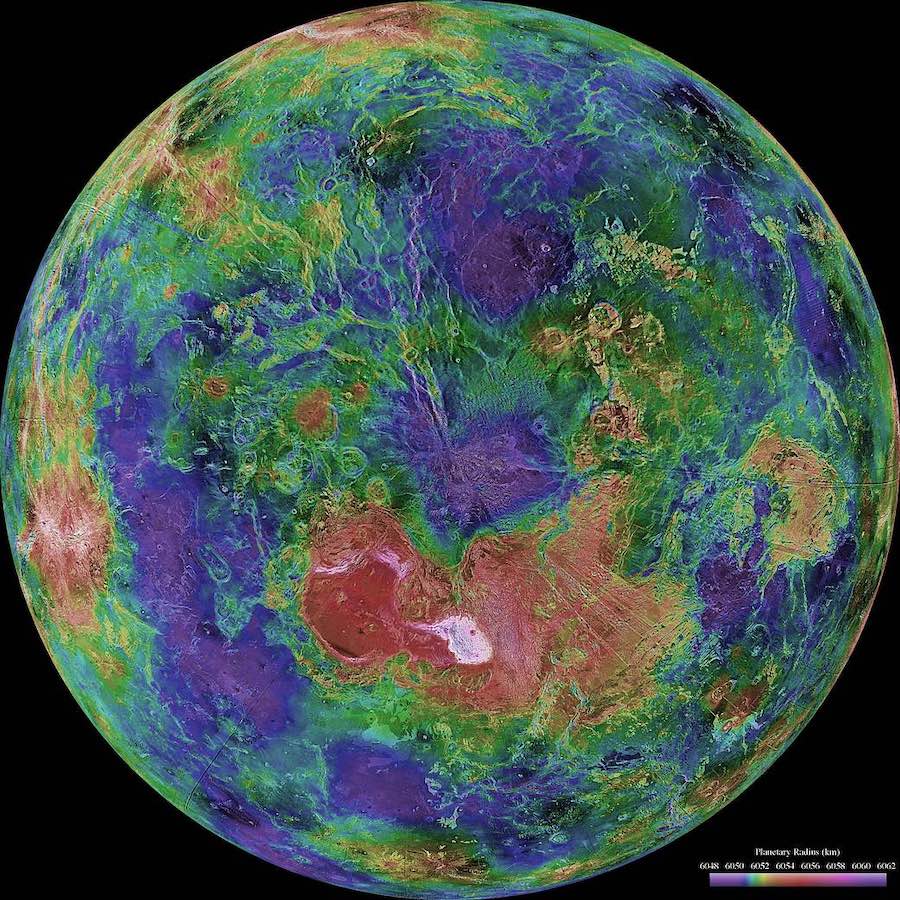

The best maps of Venus’s surface were produced by NASA’s Magellan orbiter, which bounced radar beams off the planet to measure its topography — with coarse resolution by today’s standards — from 1990 through 1994. And the last landing on Venus occurred in the 1980s.

That could change in the coming years, with several concepts for robotic missions in the running for funding from NASA, the European Space Agency, Russia, and India.

But none are sure to be approved. NASA has bypassed Venus proposals in past mission competitions, favoring robotic explorers destined for asteroids and other planets.

“It’s like being a (Chicago) Cubs fan,” joked Darby Dyar, chair of NASA’s Venus Exploration Analysis Group. “Venus just never wins.”

Meanwhile, NASA has landed spacecraft on Mars eight times, and the space agency launched the $2.7 billion Perseverance rover toward the Red Planet in July on the first leg of a round-trip mission to return Martian soil to Earth for analysis. Perseverance is the latest step in a series of interconnected missions to Mars, each building upon the discoveries and accomplishments of the one before.

The Mars landers have found that the Red Planet was habitable billions of years ago, with running water and other ingredients necessary for microbial life. So far, there’s no sign of extant life on Mars.

Like Mars, Venus has followed an arc of changing climate that stripped away the ocean of liquid water scientists believe once existed there. But instead of getting colder like Mars, Venus was enveloped in a shroud of carbon dioxide that drove a runaway greenhouse effect, pushing temperatures to extremes not found on any other planet in the solar system.

‘We have better topographic data for Pluto than we do for Venus’

“I think it’s time for NASA to start laying the foundation for a program at a different planet,” said Dyar, a planetary geologist and professor of astronomy at Mount Holyoke College.

“The knowledge gap is huge,” she said. “I always start out by saying that we have better topographic data for Pluto than we do for Venus. Imagine if we had a topographic map of Earth, and the resolution was in kilometers instead of centimeters. So we don’t know the topography. We don’t know the rock type.

“We don’t know the actual surface age very well,” Dyar said, highlighting uncertainties about whether Venus harbors active volcanoes. “Venus has a shortage of surface craters, but whether the surface is 150,000 years old or a billion years old, we don’t know.

“So there’s just an enormous amount of information that we are lacking on Venus, and it’s shameful because Venus is the only other planet in our solar system that had liquid water for over a billion years,” she said.

Dyar said Earth’s neighbor toward the sun should be a priority for exploration “because of the lines of evidence — the phosphine discovery being front and center — about the habitability of Venus.”

“I think Venus has got a bit of a tough rap,” said Beck, Rocket Lab’s founder and CEO, in a Sept. 3 press conference.

That’s a sentiment echoed by Dyar on Monday.

“I find it incongruous that we’ve spent so much time on a Mars program when the planet that actually had liquid water for a long time has been relatively unexplored,” Dyar told Spaceflight Now.

“NASA has had an emphasis on following the water and following life,” Dyar said. “Those were the slogans for the Mars program for a long time. At Venus, following water and following life requires multiple kinds of missions.”

Beck said he supports exploring Mars, but he finds Venus more intriguing.

“Venus is Earth gone wrong, and I think there’s a tremendous amount to learn from Venus, especially as we face more and more issues with climate change and trying to understand that,” Beck said. “From a scientific standpoint there’s just an incredible wealth of discovery there.”

Speaking before Monday’s announcement on the detection of phosphine, Beck identified the clouds of Venus as a particularly interesting target for research.

“For me, it’s like the ultimate treasure hunt,” Beck said. “Within a sweet zone of the Venusian atmosphere, sort of a 50-kilometer zone, the atmosphere is relatively temperate and — at least in theory — could harbor life. It might not be the life that we’re familiar with today … Really, this is a huge passion. It has been for a long time, and what bigger question is there to answer than how significant or unique life is.”

Putting together a private mission to Venus

The mission Beck is planning would send an entry probe in the atmosphere of Venus. It wouldn’t answer all the questions scientists have about Venus, but could open doors to new ways of exploring the solar system, Beck said.

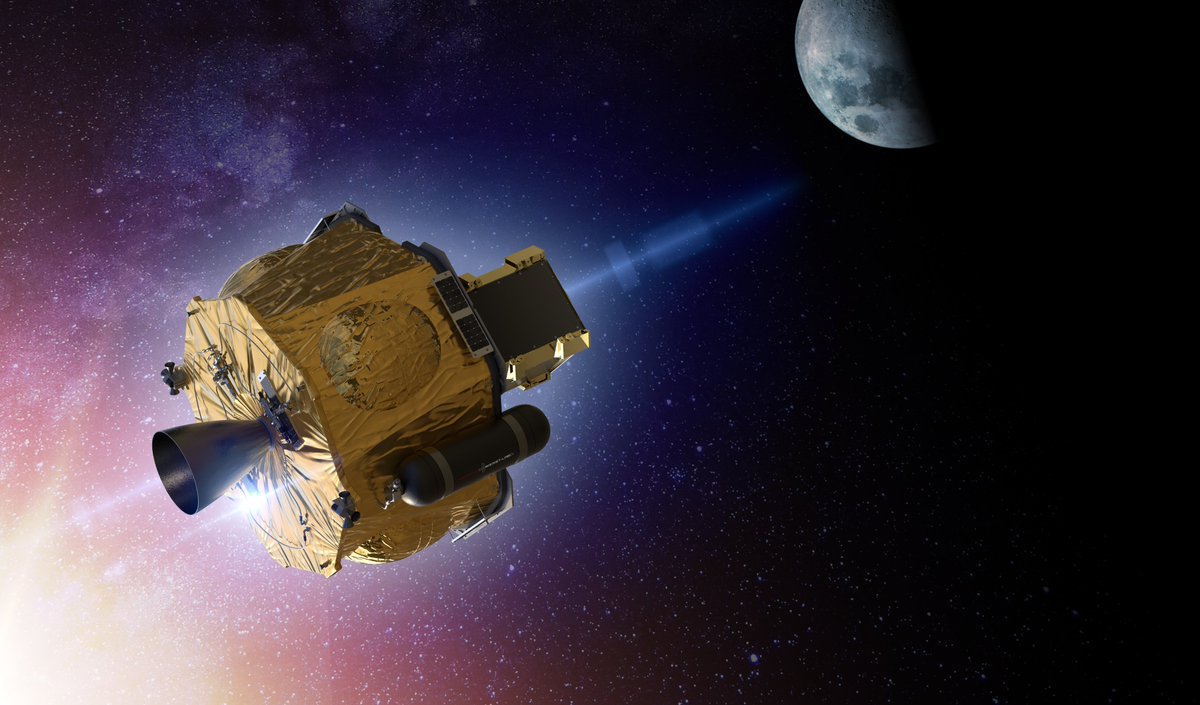

With its light-class Electron rocket and Photon spacecraft platform, Rocket Lab could deliver nearly 60 pounds — about 27 kilograms — of useful payloads to Venus, according to Beck.

“It might not sound a lot, but 27 kilograms is a lot of radio. That’s a lot of science instrument,” Beck said. “It’s a lot of really good stuff. So we can do some pretty incredible things with that.”

A fully loaded Photon spacecraft weighs a little more than 300 kilograms, or 660 pounds, when it launches on an interplanetary mission, Beck said. Most of that is propellant and on-board systems needed to carry the science payload.

The Photon is about twice the size of a standard American kitchen dishwasher. The mission concept supported by Rocket Lab would release an atmospheric entry vehicle at Venus, while the Photon mothership sails by the planet.

“The mere fact of trying is a great success,” Beck said. “Getting to Venus if a great success. If we can get a probe into the atmosphere, that’s an incredible success. The chances of us finding something that resembles life is incredibly low, but you can’t win the lottery if you don’t buy a ticket.

If Beck’s plans come to fruition, the private mission could be the next spacecraft to reach Venus. In a recent interview with Spaceflight Now, he said Rocket Lab is committed to the mission and plans to launch it by 2023.

“To lay some certainty around it, this is not a brainstorm,” he told Spaceflight Now. “So this is is not, let’s see if we can try and do it. We’re going to Venus. There are no ifs, buts, or maybes.”

Rocket Lab, a U.S. based company, launched its first Photon spacecraft into low Earth orbit Aug. 30 on a demonstration mission. Rocket Lab developed the Photon platform to accommodate a range of space sensors to support Earth-imaging, communications, and scientific missions for military, research and commercial use.

The Photon is based on Rocket Lab’s Curie kick stage, which flies on top of the company’s two-stage Electron small satellite launcher. Fitted with solar arrays, an engine, and other systems for long-duration flight in space, the Photon craft took off on top of an Electron rocket Aug. 30 from Rocket Lab’s launch site in New Zealand.

The rocket deployed a small commercial radar remote sensing satellite for Capella Space, then the Photon spacecraft — which acted as the kick stage on Aug. 30 mission — began its own in-orbit experiments. Rocket Lab announced the milestone Sept. 3, and did not disclose the Photon’s presence on the mission before launch.

Rocket Lab says the Photon will allow the company to be a one-stop shop for space missions, providing the launch vehicle and spacecraft platform to customers in an all-in-one package. Clients will only need to supply an instrument, sensor or payload to mount on the Photon spacecraft, according to Beck.

An upgraded Photon spacecraft with a more capable propulsion system will fly a NASA payload to orbit the moon next year, and the same system could be tailored for more distant destinations with few changes.

There’s no name yet for Rocket Lab’s Venus mission — Beck said he hasn’t thought about that at all — but engineers designed the Photon spacecraft with interplanetary voyages in mind.

“We have the ability to get there,” he said. “We’re building a really fantastic science team, and we have a way to sample the atmosphere.”

Beck emphasized his desire to fund the Venus mission through private sources.

“If I’m going, I’m going to Venus privately,” he said. “I think it’s super important for (it to be) a private mission because just the mere fact of trying to do it raises the bar. A private mission to another planet is something that’s never been done before, or attempted before, and I think that once you show that can be done, that leads the way for a bunch more missions in the future.”

Beck said the private space industry can make “huge advances” in exploration, similar to the way private funding helped pay for the first large astronomical telescopes.

“Typically, these things have always required governments, and I think it’s a real turning point in space if private missions can occur to other planetary bodies,” Beck said.

While he declined to disclose possible teaming arrangements with other companies and scientific institutions, Beck said Rocket Lab is working with “the best of the industry” on the Venus mission.

“We’re trying to pull together a team of some of the best in the field because one of the biggest challenges here is deciding what instrument we’re going to fly,” Beck said. “You have to make some assumptions about what you might find there to be able to design the instrument.”

Sara Seager, an astronomer and planetary scientist on the team that made the phosphine discovery, said Monday she is looking forward to partnering with Rocket Lab on a Venus mission.

“We have been talking to them,” Seager said Monday.

Seager discussed different numbers than those provided by Beck.

“Rocket Lab’s spacecraft would only be about 15 kilograms (33 pounds), and they would reserve about 3 kilograms (6.6 pounds) or so for payload,” Seager said. “So we have to work hard to make sure an instrument that would be useful for the search for life would fit into that payload, and we’re really looking forward to it.”

NASA’s contract with Rocket Lab for the launch and delivery of a compact satellite to lunar orbit next year is valued at $10 million, more than an order of magnitude less than the cost of other U.S. probes sent to the moon. The cost savings are largely driven by the miniaturization of spacecraft technology, such as instrumentation and radios for deep space missions, along with Rocket Lab’s commercial launch service.

Going to Venus may cost somewhat more than $10 million, but Beck said the figure gives a “sense what you can do with such a small amount of money.”

“That’s the thing that excites me the most, really,” Beck said. “For a pretty small amount of money, comparatively speaking, you can go do a mission like that for NASA to the moon, or go further on.”

He said a “number of interests” will fund the Venus mission, including wealthy benefactors, Rocket Lab’s own resources, and Beck himself.

“So between us all, we’ll be able to get there,” Beck said. “What I’d really love to do is not one mission, but three missions. So if anybody wants to join the team, we’d love to hear from them.

“Right now, we can get one mission, but I’d really love to do another couple of missions because that really gives us the ability to learn much more and have meaningful cracks at it.”

Rocket Lab have the mission ready for launch in early 2023. “The spacecraft design is largely complete with the lunar mission,” Beck said. “We’ll be moving pretty quickly into starting to build some hardware.”

A private mission run by Rocket Lab would be an appetizer for scientists with a hunger for fresh data on Venus.

Scientists see opportunity for Venus to grab spotlight in planetary science

Just like at Mars, scientists need a fleet of orbiters and landers to build up a better understanding of Venus and its history, Dyar said.

“And then it requires things in between that can understand the structure of the atmosphere,” she continued. “We don’t know much about the lower atmosphere below about 30 kilometers (18 miles).”

“We’d like to see really any kind of mission go back to Venus, something that’s capable of measuring gases in the atmosphere,” Seager said. “Something that has a so-called mass spectrometer that can identify larger complex molecules that can only be associated with life.”

“We’re really hoping somebody, maybe in the private space industry … might take this up,” Greaves said Monday.

Addressing the most daunting questions about Venus will require a substantial financial commitment, likely in the form a multibillion-dollar “flagship” mission, Dyar said. NASA typically builds and launches one or two robotic interplanetary flagship missions per decade.

NASA will try to launch three flagship solar system missions in the 2020s. One was the Perseverance Mars rover, and the next will be a sophisticated spacecraft to orbit Jupiter and perform repeated flybys of the icy moon Europa. The third could be a joint mission by NASA and the European Space Agency to retrieve the Martian samples gathered by the Perseverance rover for return to Earth.

That means the following flagship mission probably won’t launch until the 2030s.

An independent panel of scientists will release a report in 2022 with priorities for the next decade of solar system exploration, beyond the Europa Clipper and Mars Sample Return missions. Within budgetary limitations, NASA’s policy is to follow the science community’s recommendations.

A flagship mission to Venus might include an orbiter, a long-life lander, and a balloon that could float among the Venusian clouds. Such a project might be able to tackle many objectives at once, such as studying Venus’s geology and directly sampling Venus’s atmosphere.

“A balloon is certainly the best way,” Seager said.

The Soviet Union’s Vega missions floated balloons in the atmosphere of Venus. Similar balloons today could carry a much more moden set of instruments.

“That’s the kind of thing we’d like to see happen again,” Seager said. “Perhaps a super version of those (Vega balloons) that instead of lasting a couple of days, could last a week, months, even a couple of years.”

A Venus flagship will be in stiff competition to receive the top ranking from the decadal survey.

The decadal survey scientists will weigh a Venus mission against flagship concepts to land on Mercury, drive more than 1,000 miles across the moon, deploy a network of geophysics stations on the lunar surface, or dispatch multiple orbiters to Mars to map underground ice and collect global climate data.

Other decadal survey flagship candidates with detailed concept studies commissioned by NASA include a mission that would return samples to Earth from the icy dwarf planet Ceres, a spacecraft to orbit and land on the frozen shell of Saturn’s moon Enceladus, an orbiter and atmospheric probe to Neptune and its moon Triton, and a mission to orbit Pluto.

If Venus doesn’t come out near the top of the decadal survey’s ranking, the world’s space agencies are considering smaller-scale Venus missions in ongoing competitions for funding.

NASA last year selected four proposals from scientists for the next mission in the agency’s Discovery program, a line of cost-capped robotic interplanetary probes. Two of the missions would go to Venus, and two other concepts would travel to Neptune’s moon Triton and Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io.

After reviewing the mission proposals on their scientific merit, technical readiness and cost, NASA plans to select one or two next April for full development ahead of launch opportunities in 2026.

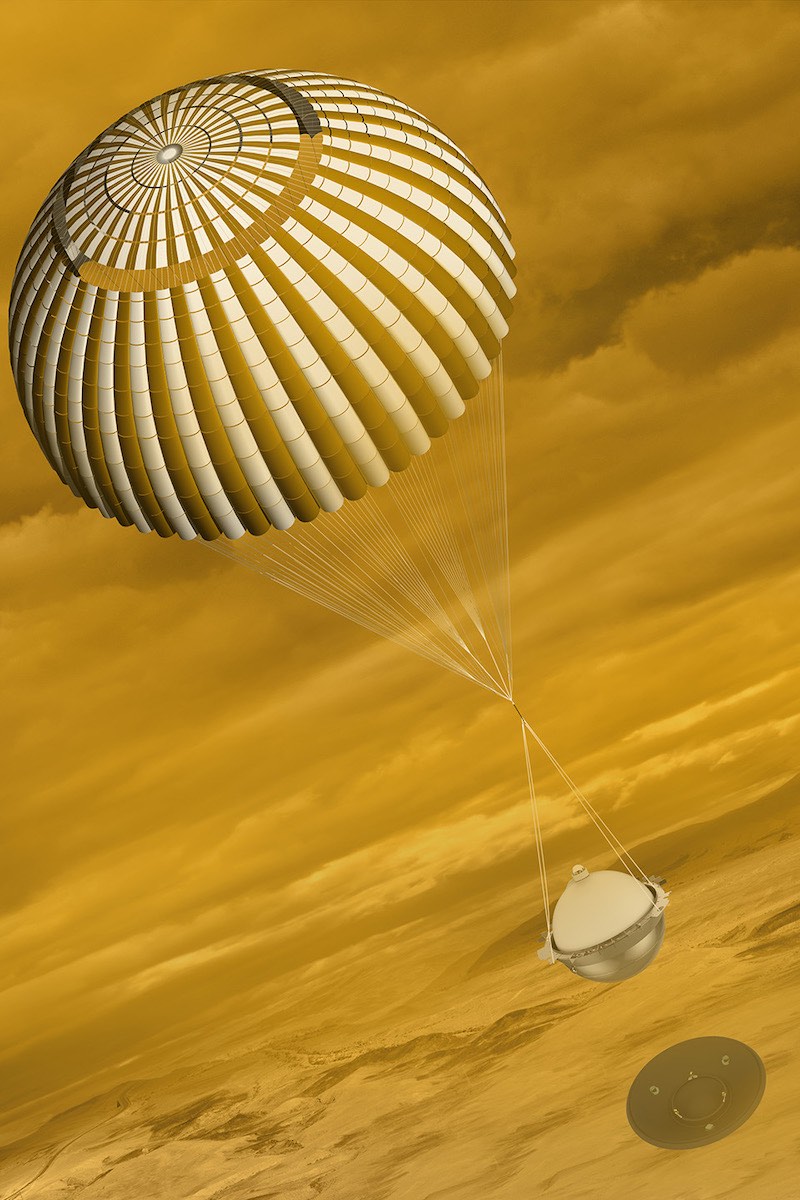

The proposed Venus missions under consideration by NASA are named VERITAS and DAVINCI+. Those names are short for Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, and Spectroscopy, and Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging Plus.

NASA has not launched a mission to Venus since 1989, when the Magellan radar mapper set off from Earth to peer beneath Venus’s thick clouds and map the planet’s volcanic landscape.

The last U.S.-led mission to send a probe into the atmosphere of Venus was Pioneer Venus in 1978. The Soviet Union’s Vega missions were the last to plunge deep into Venus’s atmosphere in 1985.

The DAVINCI+ mission would send a descent probe into the atmosphere of Venus to precisely measure its composition down to the surface, according to NASA. The mission would help scientists understand how the atmosphere formed and evolved, and accumulate more information about the history of water at Venus.

A hardened “sphere” will carry the instruments to the surface of Venus, measuring atmospheric composition and conditions at various altitudes throughout a gradual hour-long descent. Cameras on the descent sphere and an orbiter component to the mission will map surface rock types, according to NASA.

The VERITAS mission would carry a synthetic aperture radar instrument on an orbiting spacecraft to survey nearly the entire surface of the Venus, according to NASA. The VERITAS orbiter would collect data on the types of rock that make up Venus’s crust, and like DAVINCI+, would pursue signs of ancient water on the planet.

If selected by NASA, the DAVINCI+ and VERITAS missions would have to each fit under a $500 million cost cap, excluding launch expenses and international contributions.

The European Space Agency is also weighing a selection of its next medium-class, cost-capped science mission. One of the European finalists, named EnVision, is a proposed orbiter that would launch to Venus in 2032 with similar objectives as VERITAS — to map the planet in unprecedented detail with radar.

EnVision would come with a cost limit to ESA of 550 million euros, or around $650 million. Science instruments provided by other space agencies do not count against the cost cap.

Russia’s Venera-D mission is in the early stages of development. Venera-D would consist of an orbiter and a lander, with a launch no earlier than the late 2020s. The Russian mission would build on the Soviet Union’s Venera probes, which made the first soft landings on Venus.

India’s space agency also also proposed a Venus orbiter that could launch as soon as 2023 with instruments focusing on studying the planet’s hazy atmosphere. Like the NASA and European concepts, the Indian mission is awaiting final approval before proceeding into development.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.