STORY WRITTEN FOR CBS NEWS & USED WITH PERMISSION

NASA managers Thursday cleared the $1.5 billion Parker Solar Probe for launch early Saturday on a daring mission to “touch the sun,” repeatedly flying through its outer atmosphere to find out why the blazing corona is millions of degrees hotter than our star’s visible surface.

The spacecraft’s instruments also will map the sun’s powerful magnetic field, the torrent of electrically charged particles that are constantly blasted away into space in explosive outbursts and the mechanism that accelerates those particles to extreme velocities.

The goal is to understand and be better able to predict the behavior of the solar wind that triggers auroral displays on Earth and occasionally wreaks havoc with power grids and satellites.

“This space weather has a direct influence, not always positive, on our technology in space, our spacecraft, it disrupts our communications, it creates a hazardous environment for astronauts and in the most extreme cases can actually affect our power grids here on the Earth,” said Alex Young, associate director of NASA’s Heliophysics Science Division.

“So it’s of fundamental importance for us to be able to predict this space weather much like we predict weather here on Earth.”

As for the sun’s corona, the fiery halo of shimmering light seen during a total solar eclipse, scientists hope the Parker Solar Probe can answer one of their most fundamental questions.

“We’re used to the idea that if I am standing next to a camp fire and I walk away from it, it gets cooler,” Young said. “But this is not what happens on the sun. As we go from the surface of the sun, which is 10,000 degrees, and move up into the corona, we find ourselves quickly at millions of degrees.

“So this is a fundamental question that drives not only how this star works, our sun, but actually all the stars in the universe. And so, these are sort of the three fundamental questions we want to address: the speed of the solar wind, this eruptive phenomena, solar storms, and how is the corona heated?”

Nicola Fox, the Parker project scientist at Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory, described the solar probe as “the coolest hottest mission under the sun.”

“Until you actually go there and touch the sun, you really can’t answer these questions,” she said. “Why is the corona hotter than the surface of the sun? That defies the laws of nature. It’s like water flowing uphill, it shouldn’t happen. Why in this region does the solar atmosphere suddenly get so energized that it escapes from the hold of the sun and bathes all of the planets? We have not been able to answer these questions.”

But the Parker Solar Probe was built to do just that.

Perched atop a heavy-lift United Launch Alliance Delta 4 rocket, Parker will blast off from pad 37 at the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station at 3:33 a.m. EDT (GMT-4) Saturday. Forecasters are predicting a 70 percent chance of acceptable weather.

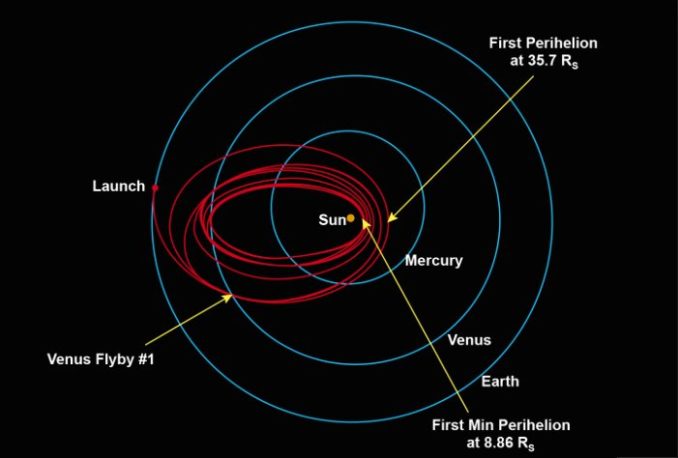

The powerful Delta 4 Heavy, ULA’s most powerful launcher, will be making only its 10th flight since 2004. It is equipped with a Northrup Grumman solid-fuel upper stage that will act to drop the Parker probe out of Earth’s 18-mile-per-second orbit around the sun, allowing it to fall inward for the first of seven gravity assist flybys of Venus over a planned seven-year mission.

“It is a beast of a rocket,” Fox said of the Delta 4. “We need to go so fast because we have to lose the influence of the Earth.”

The Venus flybys will help shape Parker’s trajectory, eventually putting the spacecraft into an elliptical orbit with a low point of just 3.8 million miles from the sun’s visible surface and a high point around the orbit of Venus.

To put that in perspective, if the Earth and sun were at opposite ends of a football field, the Parker probe would be on the four-yard line nearest the sun during close approach.

Along with being the first spacecraft to fly that close to a star, Parker also will be the fastest, streaking through the outer corona at some 430,000 mph — fast enough to fly from Washington, DC, to Tokyo in less than one minute.

Those extremes will not be seen until the later orbits, but Parker will be collecting data during all of its trips around the sun, starting with its first close encounter three months after launch.

“In our very first flyby (of the sun), we get a little more than 15 million miles away from the sun’s surface,” Fox said. “We’re still three times closer than anything has been before. … The spacecraft is staying over the same area of the sun for many, many days, allowing us to do some really incredible science on our very first flyby.”

While the corona blazes at millions of degrees, it is a tenuous environment and the heat transferred to the spacecraft will be much less. Even so, Parker’s four-inch-thick 160-pound carbon composite heat shield will be subjected to some 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit during the closest approaches, hotter than flowing lava.

But on the back side of that heat shield, where Parker’s four instruments, its flight computer and other critical systems are located, temperatures will be maintained at a relatively cool 85 degrees. Its water-cooled solar panels will be retracted behind the heat shield during close approach with just the tips exposed to the blazing light — and heat — of the sun.

“You can put your hand inside your oven and you won’t get burned unless you actually touch a surface,” said Fox. “And it really is the same. The corona is a very tenuous plasma.

“If you think about the amount of particles that actually are striking the heat shield and depositing that heat in, the whole thing gets heated up to 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit. Again, I would just say don’t touch the oven surface, don’t touch the three-million-degree plasma!”

Appropriately enough, the spacecraft is named for Eugene Parker, the University of Chicago scientist who first theorized the existence of the solar wind in 1958. Now 91, Parker, the first living scientist to have a spacecraft named in his honor, flew to the Florida Space Coast to witness his first rocket launch.

“Since this is a mission into unknown territory, we have to be prepared for some surprises, things we never thought of or things we thought of but were not correct,” he said in a recent briefing. “The heating, particularly during stormy times when the sun has a lot of flares and activity, that’s where one really doesn’t know what we’re going to find.”

The Parker Solar Probe is equipped with four instruments. The FIELDS instrument will map out the sun’s electric and magnetic fields, measuring waves and turbulence in the star’s atmosphere to help scientists understand how magnetic field lines can explosively snap apart and re-align.

The Wide-Field Imager for Parker Solar Probe, or WISPR, will photograph the large scale structure of the corona before the spacecraft flies into it, studying coronal mass ejections, jets and other phenomena.

The Solar Wind Electrons Alphas and Protons Investigation, or SWEAP, will use two instruments to characterize the particles making up the solar wind, measuring their velocity, density and temperature.

Finally, the Integrated Science Investigation of the Sun, or ISOIS, relies on two instruments to measure particle energies, shedding light on their origin and how they were accelerated.

“The science is ground breaking, it’s compelling, it’s confused scientists and puzzled us for decades and decades and decades,” Fox said. “We’re now going to fly this mission.”