A Mars orbiter developed by the United Arab Emirates in partnership with U.S. scientists has been mounted on top of a Japanese H-2A rocket and its battery charged for liftoff Tuesday from the Tanegashima Space Center.

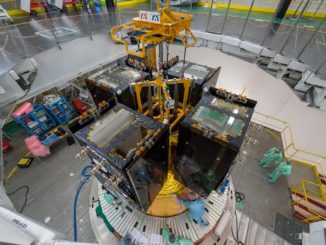

The Emirates Mars Mission — also known as Hope, or Al Amal — was raised atop the H-2A rocket July 6 inside the Vehicle Assembly Building at Tanegashima, located on an island at the southern end of the Japanese main islands.

Since then, engineers have completed a series of integrated checkouts to ensure good connections between the H-2A rocket and the Emirates Mars Mission spacecraft. Teams also completed a flight readiness review and charged the spacecraft’s battery in preparation for liftoff.

The H-2A rocket is scheduled for liftoff at 2051:27 GMT (4:51:27 p.m. EDT) Tuesday from Tanegashima, launching on a trajectory over the Pacific Ocean. After dropping its two strap-on solid rocket boosters, payload fairing, and first stage, the H-2A will ignite its cryogenic upper stage to accelerate the nearly 3,000-pound (1,350-kilogram) spacecraft on a trajectory to escape the gravitational bonds of Earth.

Liftoff of the H-2A rocket is scheduled for 5:51 a.m. local time Wednesday in Japan, around a half-hour after sunrise at Tanegashima. The UAE’s Mars probe will separate from the rocket around an hour after liftoff, then begin a sequence to unfurl its solar arrays and activate its propulsion system.

If all goes according to plan, the Hope spacecraft will become the Arab world’s first probe to reach Mars. Arrival at the Red Planet is scheduled in February 2021.

Preparations for the launch at Tanegashima proceeded without major impacts from the coronavirus pandemic, according to Omran Sharaf, project manager for the Emirates Mars Mission from the Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Centre in Dubai.

The only major hurdle involved shipping the spacecraft from Dubai to Tanegashima in April. Mission managers had to dispatch a team to Japan two weeks ahead of time to go into quarantine there before the spacecraft’s arrival.

After the quarantine, the ground crew was allowed to resume normal activities in time for the probe’s shipment from Dubai, and they helped unpack the spacecraft from its shipping crate and begin preparations for launch inside a clean room processing facility at Tanegashima.

“Obviously, there’s the social distancing that the team has to maintain, and certain measure that the team had to take into account,” Sharaf said in a recent interview with Spaceflight Now. “However, working with MHI (Mitsubishi Heavy Industries), the team managed to find ways around these challenges and actually continued the work without being impacted.”

With the spacecraft now on top of its launch vehicle, launch day is drawing near for the Hope team.

“I’m in a panic mode,” Sharaf joked.

Sarah Al Amiri, chief scientist for the Hope mission and the UAE’s minister of state for advanced sciences, said her feelings are “mixed” as teams prepare for launch.

“It’s terrified, excited, interested to see what will happen, a lot of feelings,” she said.

Around a half-day before launch, the 174-foot-tall (53-meter) H-2A rocket will emerge from the Vehicle Assembly Building and roll out to its launch pad on a perch overlooking the Pacific Ocean at Tanegashima. Riding a mobile launch platform, the journey will take about a half-hour to complete.

Once on the launch pad, the rocket will be prepared for fueling. Super-cold liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants will pump into both stages of the H-2A rocket, which will also undergo communications checks and engine steering tests to ensure the launcher is ready for takeoff.

The launch Tuesday will be the 42nd flight of an H-2A rocket since 2001, and the first H-2A launch toward Mars.

The Emirates Mars Mission cost the UAE around $200 million to design, develop and prepare for launch. That figure includes the spacecraft, ground systems and launch services, which the UAE contracted to Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, the builder of the H-2A rocket.

Sharaf said UAE space officials assessed launch providers around the world before selected MHI’s H-2A rocket for the crucial task of lifting the Hope spacecraft off the Earth.

“There were different sets of criteria we had to identify the rocket that we would like to use for our mission,” Sharaf said. “We explored different options. We looked at options in the U.S, Europe and Asia, and we settled on H-2A because it met our requirements when it comes to heritage, when it comes to performance, when it comes to launch opportunities, when it comes to being able to accommodate our system … and obviously the cost.”

The H-2A rocket has a stellar success record, with just one mission failure in 41 flights to date, and 35 straight successes since 2005.

The H-2A rocket will deploy the Hope spacecraft at a velocity of more than 21,000 mph (34,000 kilometers per hour) relative to Earth, imparting enough energy for the probe to break free of Earth and begin the voyage to Mars. The spacecraft will fine-tune is trajectory with a series of course correction maneuvers using its on-board thrusters, beginning with a burn in mid-August to begin taking aim on the Red Planet.

A critical maneuver in February 2021 will allow the spacecraft to swing into orbit around Mars, joining robotic missions already operating there from the United States, the European Space Agency and India. The UAE’s Mars mission is one of three scheduled for launch in the next few weeks, along with China’s first Mars rover and NASA’s Perseverance rover.

Launch opportunities for Mars missions come every 26 months or so, when the planets are in the proper missions to make a direct trip to the Red Planet possible

The Hope spacecraft is about the size of a Mini Cooper, and it hosts three science instruments to measure conditions in the Martian atmosphere from a unique semi-synchronous orbit high above the Red Planet.

Although the mission packs scientific punch, the government of the UAE also devised the project as a way to catalyze changes in the country’s academic and industrial sectors to focus more on technology and innovation. The mission is also timed to arrive at Mars before the 50th anniversary of the country’s independence in December 1971.

“The identity of the mission is not just about the UAE, it’s also for the Arab world,” Sharaf said. “It’s supposed to inspire the Arab youth, and send a message of hope to them, and a message that basically tells them if a country like the UAE is able to reach Mars in less than 50 years, then you guys can do much more given the history you have, given the human talent that you have.”

For their first interplanetary mission, UAE space officials partnered with engineers and scientists in the United States to help develop the Hope probe.

Emirati engineers worked alongside U.S. experts to build the spacecraft at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, or LASP, at the University of Colorado at Boulder. U.S. and Emirati scientists also developed the mission’s three instruments, with teams from the MBRSC in Dubai collaborating with researchers at LASP, Arizona State University and the University of California, Berkeley.

“One of the objectives of this mission is to develop scientific capabilities and develop researchers (in the UAE), and in the long run, develop scientists who are able to work in planetary research, focusing on Mars for now,” Al Amiri said.

The UAE government announced the Hope mission to Mars in July 2014, and officials gave the project a six-year deadline to prepare the probe for launch. The project was also given an “extremely limited” budget, Sharaf said, significantly less than other Mars missions.

NASA’s MAVEN spacecraft, which shares some of the Hope mission’s objectives, cost $671 million, more than three times the budget the UAE devoted to the Hope project. At the other end the spectrum, India’s Mars Orbiter Mission, which successfully reached the Red Planet in 2014, cost $74 million.

Mission managers looked abroad for help, finding partners in the United States who have worked on previous Mars probes. And the UAE does not have its own launch vehicle, so officials selected Japan’s H-2A rocket for the task of sending the spacecraft toward Mars.

NASA is also supporting the mission by providing tracking and communications support through the agency’s Deep Space Network, which includes huge antennas at sites in California, Spain and Australia to relay data to and from probes throughout the solar system.

“This is the philosophy we have, build on what others have, utilize existing infrastructure around the world, don’t look at it as just the UAE, and be more integrated into the global space community when it comes to developing these systems,” Sharaf said. “Part of it is for know-how transfer, and gaining experience. Another part is to reduce risks.”

The UAE’s leaders wanted the project to serve scientific and strategic purposes. The mission should inspire Arab youth, and help develop new capabilities for UAE industry and academic institutions, the government said.

But the Hope mission will also collect new types of data on the Martian atmosphere, and scientists expect to learn new insights into the planet’s weather patterns and climate.

After arriving at Mars in February, the Hope spacecraft will maneuver into an operational science orbit around April 2021 that ranges between approximately 12,400 miles (20,000 kilometers) and 26,700 miles (43,000 kilometers) above Mars.

During parts of each 55-hour orbit, the spacecraft’s move at roughly the same speed around Mars as the planet’s rotation. That will give the orbiter’s science instruments sustained views of the same region of Mars.

The Hope mission will pursue many of the same science objectives as NASA’s Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution, or MAVEN, spacecraft. MAVEN arrived at the Red Planet in 2014, and its science team is headquartered at LASP in Boulder, Colorado, the same institution involved in helping develop the Hope mission.

Scientists have analyzed data from the MAVEN mission to confirm that the bombardment of the solar wind and radiation stripped away the Martian atmosphere, transforming the planet from a warmer, wetter world into the barren planet of today.

Hope will track oxygen and hydrogen escaping from the Martian atmosphere into space, and will peer deeper into the planet’s atmosphere than MAVEN. Scientists want to investigate possible links between Martian weather and climate with the escape of atmospheric particles.

“We focus primarily on understanding the day to night cycle of the weather system on Mars throughout an entire year,” Al Amiri said. “So this will give us a better perspective on the changes that happen throughout a day, and if you project that larger, it will give us a better understanding of what happens within seasons, and from season to season in each of the hemispheres on Mars, and in all locations around the planet.

“This allows to characterize fully, for the first time, the weather system of Mars that occurs in the lower atmosphere,” Al Amiri said. “We look at the dust cycle, the temperatures on both the surface and the atmosphere up to 50 kilometers (30 miles). We look at ice clouds, water vapor cycles, and ozone … to understand the atmosphere.”

Scientists also designed Hope to help link weather in the lower atmosphere with rates of atmospheric escape, where molecules are cast away from Mars into space. The escape processes have thinned the Martian atmosphere, which was once much thicker and could have supported life.

“The coverage is a major part of making the science of the Emirates Mars Mission unique in nature, and filling in gaps in data,” Al Amiri said. “Today, we use a lot of models and climate models and theories to fill in those data gaps.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.