EDITOR’S NOTE: Launch has been delayed to Saturday, July 11, at 10:54 a.m. EDT (1454 GMT).

SpaceX raised a Falcon 9 rocket vertical Tuesday on pad 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, positioning the launch vehicle for a flight Wednesday carrying 57 more Starlink Internet satellites and two commercial Earth-imaging microsatellites for BlackSky.

The 229-foot-tall (70-meter) launcher was supposed to take off last month, but SpaceX called off a launch attempt June 26. The company said the “team needed additional time for pre-launch checkouts.”

In the end, SpaceX delayed the launch 12 days, and the company opted to shuffle order of its launches.

A Falcon 9 rocket successfully launched June 30 from pad 40 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station — a few miles to the south of pad 39A — with a U.S. military GPS navigation satellite. The Falcon 9 rocket loaded with the Starlink and BlackSky satellites rolled back to its hangar near pad 39A to await the mission’s next launch opportunity.

With the Falcon 9 standing atop pad 39A again Tuesday, SpaceX’s launch team planned perform final checkouts on the rocket and commence the countdown early Wednesday.

The Falcon 9 will be filled with super-chilled, densified kerosene and liquid oxygen propellants beginning around 35 minutes prior to liftoff, which is timed for precisely 11:59:11 a.m. EDT (1559:11 GMT) Wednesday.

There’s a 60 percent chance of acceptable weather for a midday launch Wednesday, according to the U.S. Space Force’s 45th Weather Squadron. Central Florida is in a typical summertime pattern of strong afternoon and evening thunderstorms, but forecasters said Tuesday that the latest computer model runs suggested storms may develop a bit earlier in the day Wednesday.

“While the launch window’s timeframe is still more favorable than later in the afternoon, some showers and storms moving in from the northwest cannot be ruled out,” forecasters wrote. “Because of this, the primary concern for the launch window is the cumulus cloud rule and the surface electric field rule.”

If the weather conditions cooperate, nine Merlin engines will build up to produce 1.7 million pounds of thrust, driving the Falcon 9 launcher toward the northeast from Florida’s Space Coast on the way to an orbit inclined 53 degrees to the equator.

The first stage booster launching Wednesday will make its fifth trip to space. It first flew from the Kennedy Space Center in March 2019 on an unpiloted test flight of SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft, then launched again from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California in June 2019 with three Canadian radar observation satellites.

The reusable booster also launched two Starlink missions from Florida earlier this year, according to SpaceX.

The first stage’s nine engines will fire for around two-and-a-half minutes during launch, then the booster will fall away from the Falcon 9’s upper stage. The booster will deploy four titanium grid fins for aerodynamic stability, and then fire three of its engines for a burn to target landing on SpaceX’s drone ship “Of Course I Still Love You” holding position in the Atlantic Ocean around 400 miles (630 kilometers) northeast of Cape Canaveral.

A final burn of the first stage’s center engine, followed by lowering of the booster’s four landing legs, will set up the rocket for touchdown on the floating landing vessel nearly eight-and-a-half minutes after liftoff. If the rocket sticks the landing, SpaceX will bring the booster back to Port Canaveral for inspections and refurbishment ahead of another flight.

While the first stage descends back to Earth from the edge of space, the Falcon 9’s single-use upper stage will ignite its vacuum-rated Merlin engine to propel the mission’s 59 satellite payloads into orbit.

The rocket’s payload fairing, which protects the satellites during the initial phases of launch, will jettison from the Falcon 9 at T+plus 3 minutes, 24 seconds. SpaceX’s two fairing recovery boats, named Ms. Tree and Ms. Chief, are on station in the Atlantic Ocean to retrieve the two fairing halves after they fall to Earth under parachutes.

The upper stage will shut down its engine at T+plus 8 minutes, 51 seconds, after reaching a preliminary parking orbit. A second firing of the Merlin upper stage engine more than 47 minutes after liftoff will place the 59 satellites into a near-circular orbit ranging as high as an altitude of 249 miles (401 kilometers).

The two BlackSky satellites fastened on top of the 57 Starlink satellites will be the first payloads to deploy from the Falcon 9 rocket at T+plus 61 minutes and T+plus 66 minutes.

The Falcon 9 will next release retention rods holding the Starlink satellites to the rocket, allowing the flat-panel broadband relay stations to fly away from the launch vehicle around 1 hour, 33 minutes, after liftoff,

SpaceX’s Starlink network is designed to provide low-latency, high-speed Internet service around the world. SpaceX has launched 538 flat-panel Starlink spacecraft since beginning full-scale deployment of the orbital network in May 2019, making the company the owner of the world’s largest fleet of satellites.

With Wednesday’s launch, SpaceX will have delivered 595 Starlink satellites to orbit in the last 14 months.

Each of the flat-panel satellites weighs about a quarter-ton, and are built by SpaceX in Redmond, Washington. Once in orbit, they will deploy solar panels to begin producing electricity, then activate their krypton ion thrusters to raise their altitude to around 341 miles, or 550 kilometers.

SpaceX says it needs 24 launches to provide Starlink Internet coverage over nearly all of the populated world, and 12 launches could enable coverage of higher latitude regions, such as Canada and the northern United States.

The Falcon 9 can loft up to 60 Starlink satellites — each weighing about a quarter-ton — on a single Falcon 9 launch. But launches with secondary payloads, such as BlackSky’s new Earth-imaging satellites, can carry fewer Starlinks to allow the rideshare passengers room to fit on the rocket.

The initial phase of the Starlink network will number 1,584 satellites, according to SpaceX’s regulatory filings with the Federal Communications Commission. But SpaceX plans launch thousands more satellites, depending on market demand, and the company has regulatory approval from the FCC to operate up to 12,000 Starlink relay nodes in low Earth orbit.

Elon Musk, SpaceX’s founder and CEO, says the Starlink network could earn revenue to fund the company’s ambition for interplanetary space travel, and eventually establish a human settlement on Mars.

But astronomers have raised concerns about the brightness of SpaceX’s Starlink satellites, and other companies that plan to launch large numbers of broadband satellites into low Earth orbit.

The Starlink satellites are brighter than expected, and are visible in trains soon after each launch, before spreading out and dimming as they travel higher above Earth.

SpaceX introduced a darker coating on a Starlink satellite launched in January in a bid to reduce the amount of sunlight the spacecraft reflects down to Earth. That offered some improvement, but not enough for ultra-sensitive observatories like the U.S government-funded Vera Rubin Observatory in Chile, which will collect all-sky images to study distant galaxies, stars, and search for potentially dangerous asteroids close to Earth.

SpaceX launched a satellite June 3 with a new unfolding radio-transparent sunshade to block sunlight from reaching bright surfaces on the spacecraft, such as its antennas.

All Starlink satellites beginning with the launch scheduled for Wednesday will carry the sunshade modification to reduce each spacecraft’s optical reflectivity.

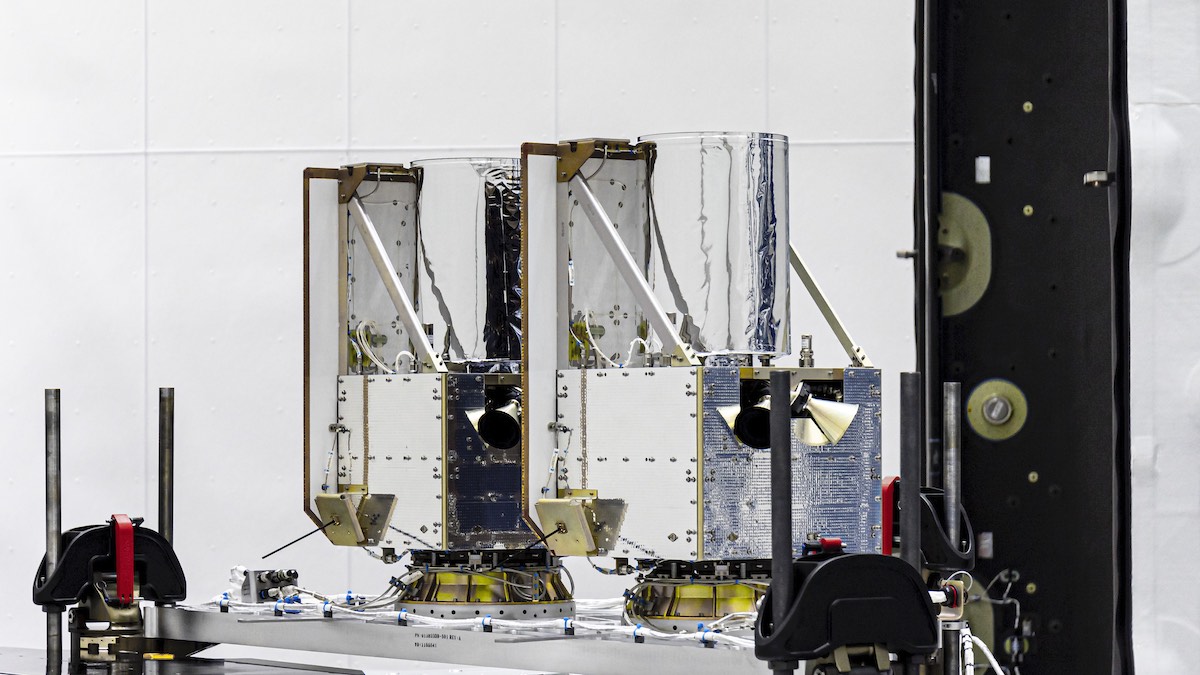

BlackSky, based in Seattle, is deploying a fleet of Earth observation satellites designed to monitor changes across Earth’s surface, feeding near real-time geospatial intelligence data to governments and corporate clients. The company’s next two satellites set for launch Wednesday are the first off a new assembly line designed to produce spacecraft at a rate of one to two per month.

The BlackSky satellites set for launch Wednesday are designated Global 7 and Global 8, but they are actually the fifth and sixth operational satellites in the BlackSky fleet.

Scott Herman, BlackSky’s chief technology officer, said the company is comfortable working with SpaceX. Spaceflight Industries, BlackSky’s parent company, has arranged rideshare missions on Falcon 9 rockets for other customers, and BlackSky’s Global 2 satellite launched on a Falcon 9 flight in 2018.

“We’ve been working with SpaceX for a long time,” Herman said. “We do work with others — the Indian space agency and Rocket Lab — but we’ve had a pretty deep relationship with SpaceX, and we’re one of their largest customers outside the U.S. government because of all the different rides we’ve been brokering.”

The BlackSky satellites launching Friday are the first produced by LeoStella, a joint venture between Spaceflight Industries and Thales Alenia Space, a major European satellite manufacturer. LeoStella’s production facility is located in Tukwila, Washington, a suburb of Seattle.

Read more about the BlackSky satellites in our earlier story.

The BlackSky spacecraft each weigh around 121 pounds, or 55 kilograms. They have electrothermal propulsion systems that use water as a propellant.

Each of the current generation of BlackSky Global spacecraft can capture up to 1,000 color images per day, with a resolution of about 3 feet (1 meter).

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.