STORY WRITTEN FOR CBS NEWS & USED WITH PERMISSION

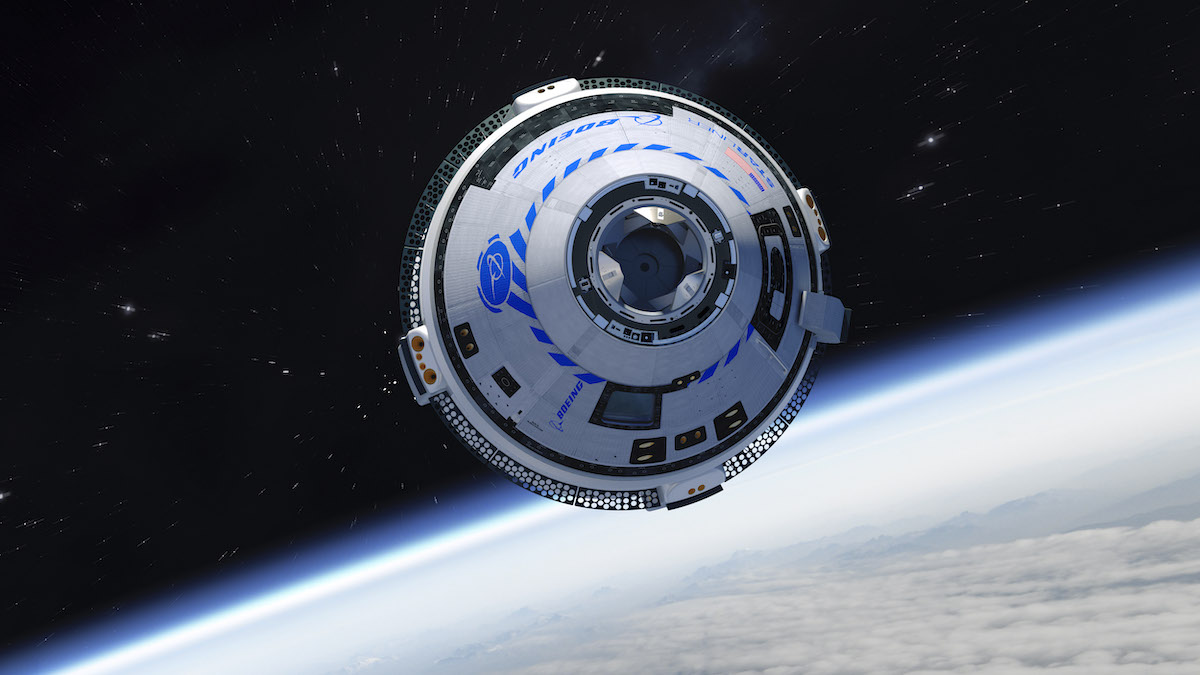

NASA has completed an exhaustive review of software problems and procedural oversights that prevented an unpiloted Boeing Starliner capsule from docking with the space station last year. The agency is implementing 80 recommendations to clear the way for a second test flight later this year and, if all goes well, Boeing’s first piloted flight next spring, officials said Tuesday.

Steve Stich, manager of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program, would not say when the company might be cleared to launch the Starliner on a repeat of the unpiloted flight other than it probably “would be toward the latter part of this year.”

“I really want Boeing and our team to go through the software recommendations and make the changes to the software and test the software,” he told reporters. “And then once we start to see how that shakes out we’ll talk a little be more about when to go fly.”

Whenever it takes off, if the flight goes smoothly — and a detailed data review confirms that — Boeing will press ahead with plans to launch a two-man one-woman crew to the International Space Station next spring aboard the same Starliner, now being refurbished, that ran into problems last December.

SpaceX has already accomplished that feat, launching two astronauts to the station May 30 aboard that company’s Crew Dragon capsule. The astronauts, Douglas Hurley and Robert Behnken, plan to return to Earth around Aug. 2, setting the stage for SpaceX’s first operational crew rotation flight in the mid September timeframe.

Asked if NASA could opt to abandon the Starliner program if Boeing runs into more problems during the upcoming unpiloted flight, Stich said the space agency is committed to having two spacecraft providers as a hedge against downstream problems that could ground either company in the midst of operational crew rotation flights.

And in any case, he said, given the reviews and additional oversight now in place as a result of the problems last December, the same sort of issues would not escape detection, well before launch, the second time around.

“We need both Boeing and SpaceX to be there for us to support crew transportation,” he said. “From what I’ve seen of Boeing’s implementation of the corrective actions, I really don’t anticipate that we would be in a position to go fly, we would not get through a flight readiness review if we saw problems, systemic problems.

“We’re going to methodically work through every single change in the software, every single change to the hardware. … I really wouldn’t anticipate getting to flight in a situation where we would repeat the kinds of close calls that we had on the (first) mission.”

Boeing and SpaceX are both building piloted astronaut ferry ships for NASA under commercial contracts valued at some $6.8 billion. The goal is to end the agency’s sole reliance on Russian Soyuz spacecraft to carry U.S. crews to and from the International Space Station.

Both companies designed, built and own their spacecraft. They both agreed to launch one unpiloted test flight to the station and one piloted mission before beginning operational crew rotation flights.

SpaceX carried out a successful unpiloted flight of its Crew Dragon capsule in March 2019 and its piloted test flight, known as Demo 2, is currently underway with Hurley and Behnken aboard the space station.

Boeing launched its Starliner on an unpiloted orbital flight test, or OFT, in December 2019. But the spacecraft’s computer set its mission clock to the wrong time before liftoff, causing it to miss a critical orbit raising maneuver. That problem, combined with a communications glitch, prevented a rendezvous and docking with the space station.

Boeing engineers then found another software oversight that could have caused the spacecraft’s service module, jettisoned prior to atmospheric entry, to crash back into the capsule.

That problem was corrected in flight, but it and the timing error later were characterized as “high visibility close calls” by NASA prompting an additional, more focused investigation and additional recommendations to address organizational issues.

Altogether, some 80 recommendations are being implemented to improve testing and simulations (21); process and operational improvements (35); software (7); requirements (10); and “knowledge capture” and hardware modifications (7).

“This is about tweaking the system, right? This is about tweaking the spacecraft and tweaking the software to make sure that these particular errors that were found are fixed,” said Kathy Lueders, former manager of the Commercial Crew Program and now the director of Human Exploration and Operations at NASA Headquarters. “So we are making progress and doing the next steps to go fly with Boeing next year.”

But few details were provided beyond general observations, in large part because Boeing, like SpaceX, is operating under a commercial contract that protects proprietary data.

Lueders said agency managers have been “struggling” with how to ensure transparency while “trying to protect the specific proprietary data that the Boeing folks have.”

“We also want to make sure that in the future, we can have this open conversation between us and our providers, so that we can ferret out issues without them being worried at the end of something being put out there that they have issues with,” she said.

“So we’re really struggling with how to be transparent and letting you see the pieces, but want to make sure that in the future … we’re not going to do something by putting out a report that then prevents open and honest conversations through our programs together.”