NASA has signed a $187 million contract with Northrop Grumman to complete the preliminary design of a pressurized crew habitat for the planned Gateway mini-space station near the moon, and agency officials have discussed new details about plans to launch first two Gateway modules on a single heavy-lift rocket.

The contract with Northrop Grumman announced June 5 covers Northrop Grumman’s work to design the Gateway’s habitation and logistics outpost, or HALO, module. The pressurized cabin will offer expanded living quarters for astronauts arriving at the Gateway on NASA’s Orion crew capsule.

“This contract award is another significant milestone in our plan to build robust and sustainable lunar operations,” said NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine in a statement. “The Gateway is a key component of NASA’s long-term Artemis architecture and the HALO capability furthers our plans for human exploration at the Moon in preparation for future human missions to Mars.”

The $187 contract announced June 5 will carry Northrop Grumman’s work on the HALO element through a preliminary design review scheduled for the end of 2020. NASA announced last year that it would award a sole-source contract with Northrop Grumman for the HALO, but a firm agreement was not announced until this month.

NASA said it will sign a separate contract with Northrop Grumman for the fabrication and assembly of the HALO for integration with the Gateway’s Power and Propulsion Element, a solar-powered spacecraft with electric thrusters being built by Maxar Technologies.

The Gateway is part of NASA’s Artemis moon program, which aims to send astronauts to the lunar surface before the end of 2024, a deadline set by the Trump administration. But NASA says the Gateway is unlikely to be part of the program’s first crewed lunar landing mission, which is expected to involve a direct link-up between an Orion crew capsule and a human-rated lunar lander around the moon, without going through the Gateway.

The HALO will be derived from Northrop Grumman’s Cygnus supply ship that flies cargo to the International Space Station. With a pressure shell made in Italy by Thales Alenia Space, the Gateway’s first habitat module will be outfitted with additional docking ports and command and control capabilities, including upgraded environmental control and life support systems, according to Northrop Grumman.

The combined function of the HALO and Orion life support systems will sustain up to four astronauts for up to 30 days on the Gateway, officials said.

“By leveraging the active Cygnus production line, Northrop Grumman has the unique capability of providing an affordable and reliable HALO module in the timeframe needed to support NASA’s Artemis program,” Northrop Grumman said.

“The success of our Cygnus spacecraft and its active production line helps to enable Northrop Grumman to deliver the HALO module,” said Steve Krein, vice president for civil and commercial satellites at Northrop Grumman. “HALO is an essential element in NASA’s long-term exploration of deep-space, and our HALO program team will continue its work in building and delivering this module in partnership with NASA.”

The docking ports on the HALO module will accommodate Orion crew capsules, lunar landers and cargo ships.

The Gateway’s unpressurized Power and Propulsion Element will serve as the service module for the mini-space station, providing electrical power generated by huge roll-out solar arrays and propulsion capability from high-power solar-electric thrusters made by Aerojet Rocketdyne.

NASA has signed a contract with SpaceX to provide logistics services to the Gateway using an extended version of the Dragon spacecraft launched aboard Falcon Heavy rockets. The Dragon XL will carry up experiments, food, supplies, spacesuits and other equipment to support astronauts on the Gateway.

In April, NASA announced agreements with Blue Origin, Dynetics and SpaceX to advance the design of crew-rated lunar lander concepts for the Artemis program.

NASA discusses new details about tandem launch of first two Gateway elements

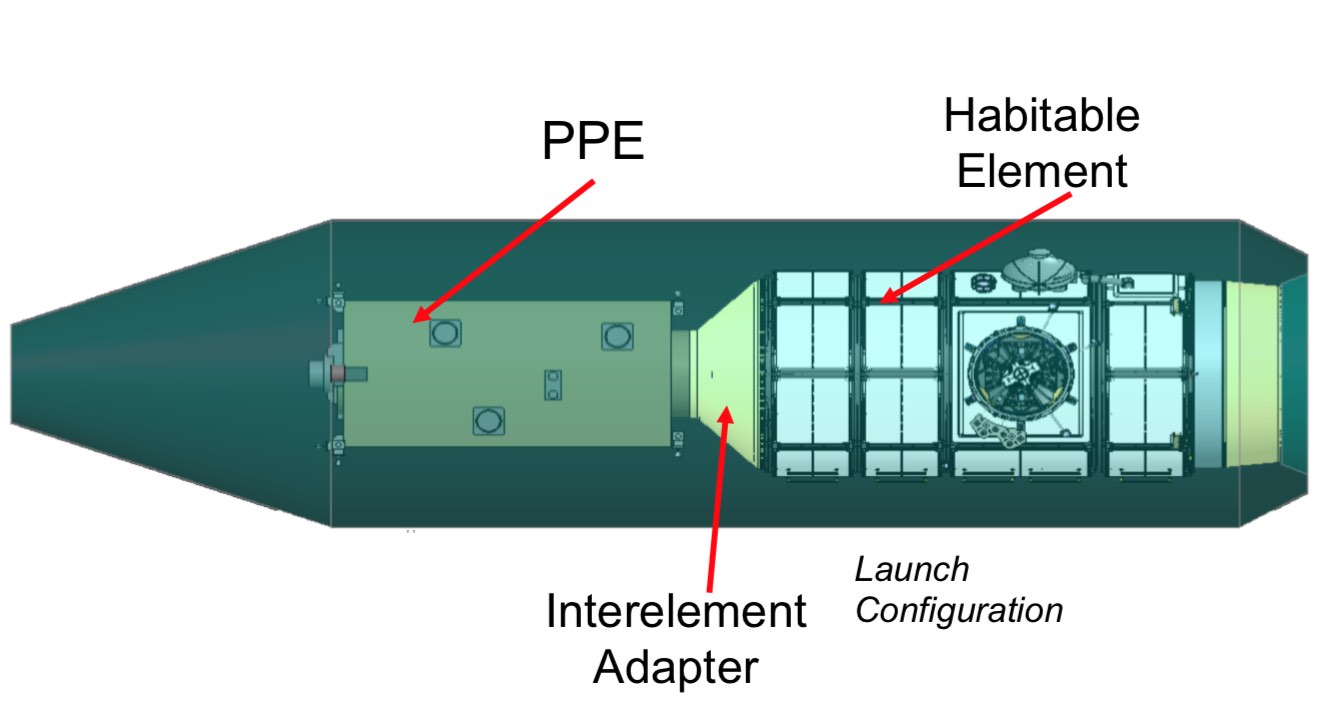

Ken Bowersox, the acting head of NASA’s human spaceflight division, said Tuesday that the agency’s plan to launch the PPE and HALO elements on the same heavy-lift rocket will require the Gateway’s solar-powered thrusters to do more of the work to position the lunar outpost into its planned orbit around the moon.

NASA has not selected a rocket to carry the two modules into space, but the massive payload could fit on a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket with a lengthened payload fairing currently in development to accommodate large U.S. military satellites, officials said. A final selection of a launch vehicle for the Gateway modules is expected before the end of this year.

Agency managers previously intended to launch the PPE module and the HALO on separate rockets in 2022 and 2023. Now the combined elements are scheduled for launch in November 2023, according to Dan Hartman, NASA’s Gateway program manager.

The tandem launch will allow engineers to connect the modules together on the ground at the Kennedy Space Center, rather than having to perform an automated docking in the vicinity of the moon. The connections involve structural, mechanical, power and fluids interfaces.

Northrop Grumman will handle the connections between the HALO and the Maxar-built Power and Propulsion Element.

That will save money and reduce risk, according to NASA.

Rather than launching directly on a trajectory toward the moon, the first two Gateway modules will deploy off their launch vehicle in a high-altitude orbit around Earth, then head to an elliptical halo orbit around the moon.

“When we decided to integrate the PPE and the HALO, we realized that we weren’t going to be able to get the elements all the way out to the moon with the launch vehicle,” Bowersox said Tuesday. “What would work better was to get them into a high orbit and then use the solar-electric propulsion to get out to cislunar space, so that’s our plan now.”

NASA says the Gateway will have several missions, including demonstrating technologies for future deep space missions, such as human expeditions to Mars. Many engineers consider high-power solar-electric propulsion, which uses electricity and an inert gas to produce thrust, as an essential technology for long-duration flights to Mars.

“The great part about that plan is we’re going to get lots of run time on those solar-electric engines, and we’re going to get the run time very early in the vehicle’s life,” Bowersox said. “So Gateway will already have served a big part of its purpose within its first year of life, and then we’ll be able to add additional (xenon) fuel to the gateway, get more information on how long those engines last in addition to supporting the work on the lunar surface.”

The Gateway will also act as a safe haven for astronauts heading to the lunar surface, and it will offer a staging point for lunar landers, allowing the vehicles to eventually be refueled and reused for multiple trips to and from the moon.

But NASA has deferred some work on the Gateway in favor of accelerating development of crewed lunar landing vehicles. While the Gateway could provide communications relay support for the Artemis program’s first lunar landing mission with astronauts, crews are not expected to visit the Gateway until at least 2025.

NASA has often emphasized the Gateway’s ability to host scientific payloads for solar and astronomical research, alongside biological and radiation experiments, and lunar research instruments. But much of those capabilities will come later, once international elements are added to the Gateway.

Canada is developing a new robotic arm for the Gateway station, and Japanese and European space agencies are working on larger habitation module and a refueling and communications package for the outpost in lunar orbit.

“We want to use Gateway for as much science as we can, but as we descope Gateway, we’re going to have just less surface area on the outside, less surface area on the inside, so we’re not going to have as much room for different science investigations,” Bowersox said Tuesday. “But we want to get as much out of it as we can.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.