EDITOR’S NOTE: Updated Dec. 4 after scrub.

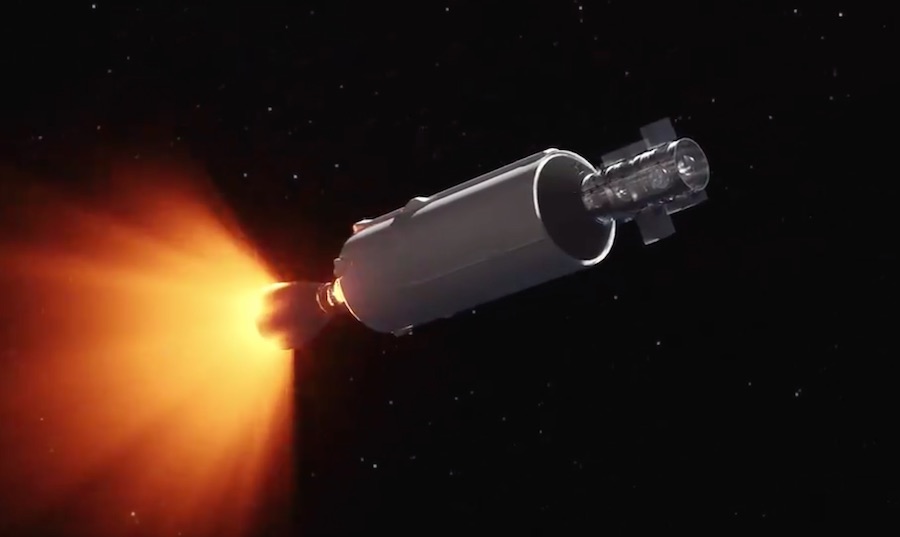

SpaceX will perform a multi-hour experiment on the second stage of a Falcon 9 rocket after the launcher deploys a Dragon supply ship on the way to the International Space Station Thursday, gathering thermal data and other information to verify the vehicle’s ability to perform long-duration missions and inject payloads into demanding, high-energy orbits.

The experiment will use up some of the Falcon 9’s excess lift capacity, leaving an insufficient fuel reserve in the rocket’s first stage to perform maneuvers to return to a propulsive landing at SpaceX’s recovery site at Cape Canaveral. Instead, the first stage will aim for a landing on a SpaceX drone ship parked in the Atlantic Ocean.

SpaceX scrubbed Falcon 9 launch attempt Wednesday due to brisk upper level winds and poor conditions in the offshore first stage landing zone.

“After Dragon is dropped off into orbit, the Falcon 9 second stage stage is going to continue on for a thermal demonstration,” said Jessica Jensen, director of Dragon mission management at SpaceX. “So it’s going to be a long six-hour coast that then results in a disposal burn.

“We need extra performance for that demonstration, so basically what we have to do is burn the first stage for a longer period of time, so that the second stage can have its performance reserved for that demo,” Jensen said Tuesday. “Since we’re burning the first stage for a longer period of time, it doesn’t have as much fuel to come all the way back to the launch site. So we’ll do a partial boost-back, which is where the drone ship is located.”

On Thursday’s flight — SpaceX’s 19th cargo launch to the space station — nine kerosene-fueled Merlin 1D engines on the Falcon 9’s first stage will cut off at T+plus 2 minutes, 31 seconds, before separating to allow the rocket’s single-engine second stage to accelerate the Dragon capsule into orbit.

That burn time is about 13 seconds longer than the first stage firing on SpaceX’s most recent Dragon cargo launch in July, when the booster had enough leftover propellant to return to a landing at Cape Canaveral.

Jensen said SpaceX is performing the thermal demonstration on Thursday’s launch for “some of our other customers for longer missions that we’re going to have to fly in the future.”

She said SpaceX will measure the thermal environment in the second stage propellant tanks, along with other parameters, then reignite the stage’s single Merlin engine for a disposal burn.

SpaceX’s acknowledgement of the bonus objectives planned on this week’s Falcon 9 launch helps explain an unusual airspace warning notice, or NOTAM, indicating the rocket’s second stage would deorbit and fall back into Earth’s atmosphere over the far southern Indian Ocean. Most of the rocket body is expected to burn up during re-entry.

The timing and location of the NOTAM hinted that SpaceX planned something unusual for the Falcon 9’s second stage after releasing the Dragon cargo capsule in orbit, according to Marco Langbroek, an experienced tracker of satellite movements who lives in the Netherlands.

In a blog post, Langbroek wrote that the airspace warning suggests the Falcon 9 rocket will steer into a higher-inclination orbit after deploying the Dragon spacecraft into the space station’s orbital plane inclined 51.6 degrees to the equator. The NOTAM indicates the upper stage will deorbit around five-and-a-half hours after launch.

SpaceX has performed long-duration missions on two Falcon Heavy launches to date.

During the company’s first Falcon Heavy test flight in February 2018, the rocket’s second stage reignited its upper stage engine after coasting in orbit more than five hours, a maneuver that sent a repurposed Tesla Roadster on a trajectory to escape the grip of Earth’s gravity.

A Falcon Heavy mission in June for the U.S. Air Force included four upper stage engine burns over three-and-a-half hours to deploy two dozen satellites into three different orbits around Earth.

Long-duration missions lasting more than five-to-six hours are required to place satellites on trajectories high above Earth, such as circular geosynchronous orbits, where spacecraft linger over the same geographic region at an altitude of more than 22,000 miles (nearly 36,000 kilometers) over the equator.

While SpaceX did not identify what customers might need a long-duration launch profile, some of the U.S. government’s top secret spy satellites require direct rides to geosynchronous orbits. The Delta 4-Heavy rocket built and flown by United Launch Alliance often delivers those clandestine payloads to space, but ULA is retiring the Delta 4-Heavy. ULA’s next-generation Vulcan Centaur rocket and SpaceX’s launch vehicles are less expensive than the Delta 4-Heavy, which has launched 11 times since 2004.

The U.S. Air Force also occasionally flies satellite missions that require multi-hour launch profiles.

In contrast, SpaceX’s Dragon missions to the International Space Station reach their targeted deployment orbits in less than 10 minutes. A commercial communications satellite is typically released from the Falcon 9 launcher around a half-hour after liftoff.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.