Standing in front of a shiny full-scale prototype of SpaceX’s Starship vehicle in South Texas, Elon Musk said Saturday night he wants the company’s gigantic next-generation rocket to fly into orbit within six months, a bold schedule that he acknowledged requires “exponential” improvements in design and manufacturing.

Regardless of when the futuristic-looking vehicle reaches orbit for the first time, Musk told several hundred employees, local supporters, space enthusiasts and space reporters — along with thousands more watching online — that SpaceX will build a fleet of Starships and launch them from sites in Texas and Florida.

The first full-size prototype of SpaceX’s Starship space vehicle — named Starship Mk. 1 and built this summer on the South Texas coast — should be ready to launch on a high-altitude atmospheric test flight in the next one or two months, Musk said.

SpaceX plans to practice launching and landing the Starship with suborbital up-and-down flights, similar to the way engineers perfected landings of Falcon rocket boosters with an experimental vehicle named “Grasshopper.”

“What’s really kind of hard to grasp, at a visceral level, is that this giant ship will do the same thing that Grasshopper did,” Musk said, backdropped by the Starhopper prototype. “This thing is going to take off, fly to 65,000 feet — about 20 kilometers — and come back and land in about one to two months… So that giant thing, it’s really going to be pretty epic to see that thing take off and come back.”

“Yeah, it’s wild,” he added.

Musk, an avowed optimist, said an orbital launch attempt with Starship, and its not-yet-built Super Heavy first stage booster, could happen next year.

“With any development into uncharted territory, it’s difficult to predict these things with precision,” he said. “But I do think things are going to move very fast. So, our plan is in basically in one to two months to do the 20-kilometer flight with Starship Mk. 1. Our next flight after that might actually just be all the way to orbit with a booster and the ship.”

SpaceX says the reusable Starship and Super Heavy will eventually replace the company’s Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets, along with the Dragon cargo and crew capsules.

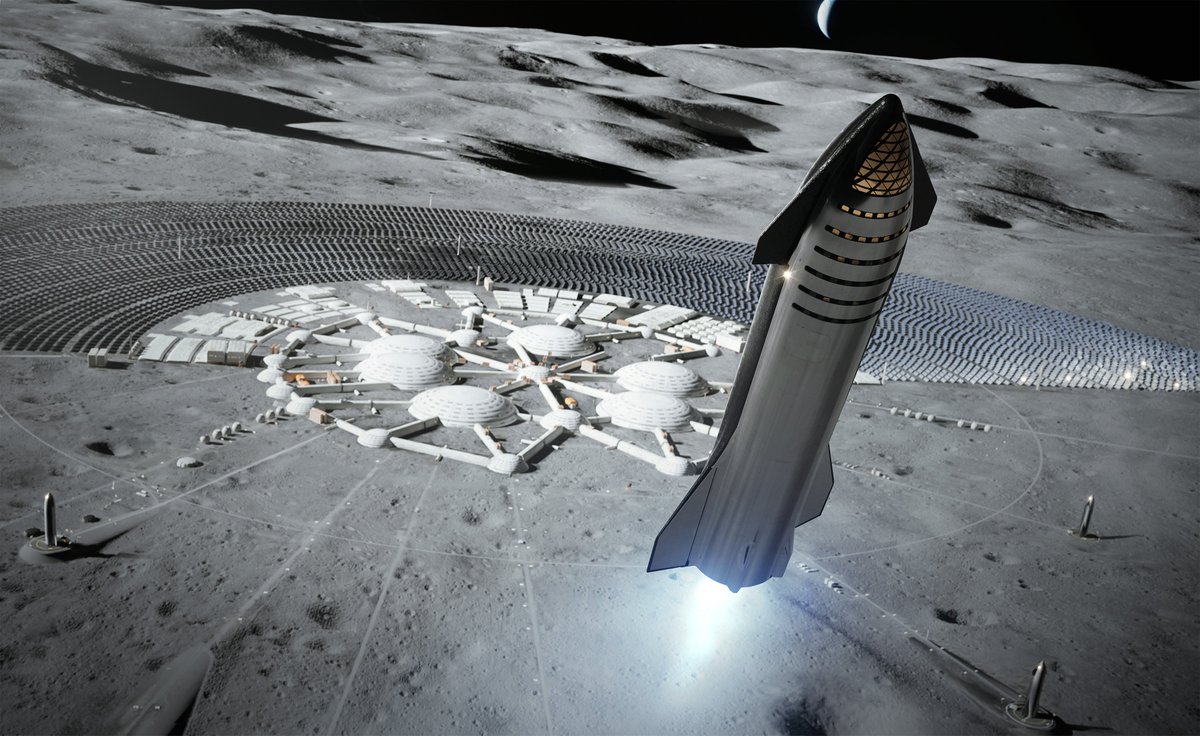

According to SpaceX’s website, the Starship and Super Heavy will be able to deliver satellites to orbit at a “lower marginal cost per launch than our current Falcon vehicles.” But SpaceX says the next-generation booster and spaceship can do much more, including interplanetary flights to the moon, Mars and other destinations with up to 150 tons of cargo, or crews of up to 100 people.

Musk’s presentation Saturday came three years after he first unveiled the deep space transportation architecture that became the Starship and Super Heavy. SpaceX has since settled on a smaller, but still record-large, rocket than the design Musk presented in 2016.

The Starship and Super Heavy are designed for vertical takeoffs and landings, similar to the method SpaceX uses to return Falcon rocket boosters to Earth for refurbishment and reuse. During orbital launches, the Super Heavy booster will propel the Starship toward space before detaching and returning to a landing near the launch site. The Starship will then accelerate into orbit on its own.

“I have this mantra called, ‘If a schedule’s long, it’s wrong, if it’s tight, it’s right,'” he said. “If the design takes a long time to build, it’s the wrong design. This is the fundamental thing. The tendency is to complicate things.

“I have another thing, the best part is no part, the best process is no process,” Musk said. “It weighs nothing, costs nothing, can’t go wrong … The thing I’m most impressed with when I have design meetings at SpaceX is, ‘What did you undesign?’ Undesigning is the best thing. Just delete it, that’s the best thing.”

That ethos led SpaceX to assemble the first Starship prototypes in the open in public view, not inside a climate-controlled factory with strict cleanliness requirements. Musk said it would have taken too long to construct a dedicated assembly building for the Starship.

And instead of building the vehicle out of carbon fiber, as many modern rockets use, the Starship is made of stainless steel. The structures of modern launch vehicles are primarily made of carbon fiber or aluminum, but rockets designed in an earlier era, such as the Atlas-Centaur conceived in the 1950s and 1960s, flew with a stainless steel skin.

“Up until October of last year, we were pursuing a completely different design,” Musk said, referring to SpaceX’s switch to a stainless steel structure for the Starship, reversing earlier plans to construct it out of carbon fiber.

Less than a year after the redesign, Musk has a full-size Starship prototype on the verge of its first test flight. SpaceX says a Super Heavy first stage, which will stack under the Starship during an orbital launch, is not far behind.

Stainless steel is heavier than other rocket materials, but it comes with several major benefits that ultimately make the entire vehicle, including its heat shield, lighter than otherwise possible, Musk said.

Stainless steel is resilient and strong at super-cold temperatures. That’s important because the Starship and Super Heavy will be loaded with 9 million pounds of cryogenic methane and liquid oxygen at liftoff.

“The best design decision on this whole thing is 301 stainless steel because at cryogenic temperatures, 301 stainless actually has about the same effective strength as an advanced composite or aluminum-lithium,” Musk said. “Unlike most steels, which get brittle at low temperature, 301 stainless gets much stronger.

“Its strength-to-weight ratio at cryogenic temperatures is equivalent, or even perhaps slightly better than, advanced composites or aluminum-lithium,” he said. “This is not well appreciated because if you just look at the materials manual and say what is the strength of stainless steel, it looks much weaker than it is. (If) you say what is the strength at cryogenic temperature … much, much stronger at very low temperature, almost twice as strong. That’s when it becomes better than carbon fiber or aluminum-lithium.”

Steel has a melting temperature of around 2,700 degrees Fahrenheit (1,500 degrees Celsius), significantly higher than that of the aluminum structure used on the space shuttle orbiter.

“For a reusable ship, you’re coming in like a meteor,” Musk said. “You want something that does not melt at a low temperature. You want something that melts at a high temperature, and this is where steel is extremely good as well.”

That means the top side of the Starship will not need a heat shield, and the thermal shielding on the side of the vehicle oriented forward during re-entry into the atmosphere will be “massively reduced,” Musk said.

“Because the steel can take a much higher temperature, your heat shield even on the windward side is much lighter,” he said. “The net effect is that a 301 stainless steel rocket is actually the lightest possible reusable architecture.”

A ton of stainless steel is 2 percent the cost of a ton of carbon fiber, Musk said.

“Also, it’s very easy to weld stainless steel, the evidence being that we welded it outdoors without a factory,” he said. “With carbon fiber this is impossible, with aluminum-lithium, also impossible. But steel is easy to weld and it is resilient to the elements.”

For orbital-class Starships, SpaceX plans to install hexagonal ceramic tiles on the bottom side of the vehicle. The tiles will take the brunt of re-entry heating as the ship falls into the atmosphere at an angle of attack of around 60 degrees.

The ship will then free-fall in a horizontal orientation — “like a skydiver,” Musk said — using fins and thrusters for stability before flipping vertical and igniting its base engines for a vertical landing.

SpaceX is building a second Starship prototype, designated Mk. 2, at an industrial yard in Cocoa, Florida, near Cape Canaveral. Once complete, the vehicle will be transported to the nearby Kennedy Space Center for testing at launch pad 39A, a former Apollo and space shuttle launch facility now leased by SpaceX for its Falcon rocket family.

“I’m giving you literally just stream of consciousness here,” Musk said Saturday at SpaceX’s launch site at Boca Chica, Texas. “Most likely, we would not fly to orbit with Mk 1, but we would fly to orbit with Mk. 3, which will be built after Mk. 1 right here. In fact, we’ll start building it in about a month.

A few minutes later, Musk said the SpaceX would probably launch the first Starship into orbit using the Mk. 4 or Mk. 5 vehicle.

“Just to frame things, we are going to be building ships and boosters at both Boca and the Cape as fast as we can,” he said. “It’s going to be really nutty to see a bunch of these things, not just one, but a whole stack of them. We’re improving both the design and the manufacturing method exponentially.”

For example, the third iteration of SpaceX’s Starship will be built in fewer pieces, with thinner walls, a lighter structure, and lower costs, he said.

“The rate at which we’re going to be building ships will be quite crazy by space standards,” he said. “I think we’ll have Mk. 2 (in Florida) built within a couple of months or less, and Mk. 3, maybe three months, that type of thing. Mk. 4, four months, maybe five months. And we would seek to go to orbit with probably Mk. 4 or Mk. 5.”

“This is going to sound totally nuts, but I think we want to try to reach orbit in less than six months,” Musk said. “Provided the rate of design improvement and manufacturing improvement continue to be exponential, I think that is accurate to within a few months.”

The Starship alone could “probably” reach orbit without a boost from the massive Super Heavy first stage, but flying it to orbit in that configuration wouldn’t make sense, Musk said. Without the help of a booster, the Starship could not carry a heat shield, extra fuel or other equipment to return to Earth intact.

So far, SpaceX’s development of the Super Heavy and Starship has been privately-funded through revenues from Falcon and Dragon missions. SpaceX has also raised more than $1 billion this year from investors, largely to fund the company’s Starlink program designed to provide Internet services from space.

SpaceX says future revenue from the Starlink business could be applied to the Super Heavy and Starship projects.

“The priority is to build at least two Starships at each site — at Boca and at the Cape — and then start building the (Super Heavy) booster,” Musk said. “We’ll complete Mk. 1 through 4 before doing Mk. 1 of the booster. And then we’ll do Mk. 1 and Mk. 2 of the boosters at the Cape and at Boca.”

Clusters of methane-fueled Raptor engines will power the Super Heavy and Starship vehicles.

Three Raptors are mounted to the base of the Starship Mk. 1 prototype at Boca Chica, and three more will be installed on the Mk. 2 vehicle in Florida for initial test flights, Musk said.

The Raptor is the most powerful engine ever built by SpaceX. The early version of the Raptor engine can produce up to 440,000 pounds of thrust at sea level, roughly equivalent to the main engines flown on the space shuttle.

The Raptor engine has more than twice the thrust of the kerosene-burning Merlin 1D engine that flies on SpaceX’s Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets. And the Raptor is the most powerful methane-fueled engine ever flown.

Orbital-class Starships will have six Raptors — three gimbaling center-mounted engines for vertical landings, and three engines with expanded nozzles optimized for firings in space.

The Super Heavy booster could accommodate up to 37 Raptor engines, depending on final design decisions and mission requirements, Musk said. He expects the Super Heavy to generate around 15 million pounds of thrust at liftoff, about two times the thrust generated by the gigantic Saturn 5 rocket used for the Apollo moon landing missions.

“The main constraint on launching the booster is engines,” Musk said. “The booster has a lot of engines. So spooling up the Raptor production rate is extremely important — vital — to completing the booster. Doing the tanks and the legs and the grid fins, that is not a constraint. That we can get done fast. I think we’d want to have at least probably 24 engines, but I think really at least 31 engines to launch.”

The Super Heavy will likely fly with seven Raptor engines with the ability to gimbal, or swivel, to provide steering. The rest of the booster engines will have fixed nozzles, Musk said.

“Including development engines from now through orbit, we probably need 100 Raptor engines. Our production rate right now is maybe one every eight to 10 days,” he said.

By next year, SpaceX wants to build a Raptor engine every day.

The Starship vehicle assembled at Boca Chica stands around 164 feet (50 meters) tall and weighs 200 tons without propellants. It measures around 30 feet (9 meters) in diameter, about one-and-a-half times the diameter of a Boeing 747 jumbo jet.

Combined with the Super Heavy first stage, the entire stack will stand around 387 feet (118 meters) tall.

The fully reusable Super Heavy/Starship launch vehicle will be able to loft some 150 tons of payload to low Earth orbit, Musk said.

Assuming the Starship can be refilled with methane and liquid oxygen in orbit, the vehicle can deliver the same mass to the moon or Mars, he said.

Musk, an avowed optimist, said people could ride into space on Starship flights before the end of next year.

“I think we could potentially see people flying next year,” he said. “It’s designed to be a reusable rocket, so we can do many flights to prove out the reliability very quickly. With an expendable vehicle, if you want to do 10 flights, let’s say, to prove out the viability of an expendable vehicle, you need to build and destroy 10 vehicles, whereas we can do 10 flights within basically 10 days.

“When I say rapid reusability, I mean you can fly the booster 20 times a day, you fly the ship three or four times a day. That’s what I mean by reusability.”

Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa announced last year he plans to fly on SpaceX’s next-generation spaceship, along with a crew of artists, on a flight around the moon as soon as 2023.

SpaceX says the “aspirational goal” is to make the Starship ready for a flight to Mars without humans in 2022. A crewed flight to the Red Planet could follow as soon as 2024.

While he didn’t mention it Saturday night, Musk has previously said the Starship could be used for point-to-point transportation around Earth, enabling intercontinental flights in minutes instead of hours.

Musk’s presentation Saturday was heavy on propulsion systems, structural design, aerodynamics and vision, but light on talk of funding or technologies necessary to sustain Starship crews in space, which SpaceX says may number as many as 100 people at a time.

“For sure, you’d want to have a regenerative live support system,” Musk said in response to a question. “That just means you’re recycling everything. That’s for sure important if you’re on a several-month journey to Mars and on the surface for 18 months. Regenerative is kind of a necessity. I don’t think it’s actually super-hard to do that relative to the spacecraft itself. The life support system is pretty straightforward.”

Musk suggested work on life support systems will come later because the Starship’s first flights will be unpiloted.

“The early flights of Starship would not have any people on-board,” he said. “It would just be in automatic mode. It would only be later flights that would have people on-board. Even the first flights to Mars, we would send at least a couple of ships, (and) have them land automatically before sending people.”

SpaceX’s Crew Dragon capsule, designed to ferry NASA astronauts to the International Space Station, will be the company’s first human-rated spaceship. But it’s designed for a limited purpose, and has basic life support systems to accommodate crews for a few days during trips to and from the space station.

And SpaceX’s Crew Dragon has not yet flown into orbit with astronauts. Musk said in an interview with CNN after Saturday night’s presentation that hardware for a high-altitude abort test will arrive at Cape Canaveral next month, and hardware for the first Crew Dragon mission with astronauts will arrive in November.

He did not specify any schedule for the Crew Dragon launches themselves.

Musk hosted a presentation similar to Saturday’s event in May 2014 to reveal details about the Crew Dragon spacecraft. At that time, Musk said the Crew Dragon would be ready to carry astronauts to space in 2016.

For long-duration voyages to other other worlds, SpaceX’s Starship will need a much more elaborate life support system to regulate oxygen and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, store and process human waste, generate drinking water, and perhaps grow vegetables on-board.

NASA is testing some “closed-loop” life support system technologies on the space station, with more upgrades set for launch to the orbiting research complex in the next few years.

SpaceX and NASA have enjoyed a symbiotic relationship for more than a decade, beginning with the U.S. space agency’s award of a $278 million agreement to SpaceX in 2006 — just four years after its founding — to demonstrate the delivery and return of space station cargo.

SpaceX has delivered on the cargo contract, and continues to provide regular resupply flights to the station. The Dragon capsule is also the only spacecraft currently flying that is capable of returning significant mass from the station back to Earth.

The early NASA investment also gave SpaceX an anchor customer for the Falcon 9 rocket, which has become a market leader in the global commercial launch business, prompting competitors to cut prices. It also pioneered the vertical landing and reuse of rocket boosters, a crucial capability for Musk’s vision of expanding human civilization to Mars.

Since 2006, SpaceX has received $7.7 billion in contract awards from NASA for space station cargo and crew transportation through 2024, according to a report released last year by NASA’s inspector general.

NASA selected SpaceX and Boeing in 2014 to develop and fly new human-rated space capsules — the Crew Dragon and Starliner — to carry astronauts to and from the space station. The commercial crew program was conceived to limit the gap in U.S. human spaceflight capability after the space shuttle’s retirement in 2011.

Despite the deep bond between NASA and SpaceX, the U.S. government, so far, has little role in the privately-run Starship program.

NASA is focusing on the Space Launch System, Orion spacecraft and the development of a commercial lunar lander to achieve the Trump administration’s goal of landing astronauts the moon by 2024.

SpaceX wrote in an environmental impact statement outlining the company’s future construction plans at the Kennedy Space Center that the development of the Super Heavy/Starship vehicle “may support NASA in meeting the U.S. goal of near-term lunar exploration.”

Delays in the commercial program were revisited Friday in a written statement from NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine.

“I am looking forward to the SpaceX announcement tomorrow,” Bridenstine said Friday. “In the meantime, commercial crew is years behind schedule. NASA expects to see the same level of enthusiasm focused on the investments of the American taxpayer. It’s time to deliver.”

A series of redesigns and technical delays have been partly responsible for schedule slips on the Boeing and SpaceX commercial crew programs. For example, problems with the abort engines on Boeing’s Starliner crew capsule delayed critical testing by nearly a year, and a valve failure led to the explosion of a Crew Dragon spacecraft during a ground test in April.

But some of the commercial crew delays were caused by Congress, which failed to provide the funding NASA said it needed for the space taxi program prior to 2015.

In June, the Government Accountability Office raised workload concerns for NASA engineers tasked with reviewing a high volume of data submitted by Boeing and SpaceX teams as they finalize their designs and test plans.

The reviews are aimed at ensuring the contractors comply with NASA safety requirements.

“NASA’s ability to process certification data packages for its two contractors continues to create uncertainty about the timing of certification,” the GAO said. “The program has made progress conducting these reviews but much work remains.”

Musk responded to Bridenstine’s apparent criticism Saturday night.

“From a SpaceX resource standpoint, our resources are overwhelmingly on Falcon and Dragon,” he said. “Just to be clear, it’s a small percentage of SpaceX that does Starship, less than 5 percent of the company.”

The U.S. Air Force, which needs powerful new rockets to carry satellites into orbit, has funded a fraction of the Raptor engine’s development costs. But the military did not select SpaceX last year as part of a round of rocket development contracts that went to SpaceX rivals United Launch Alliance, Blue Origin and Northrop Grumman.

SpaceX filed a lawsuit against the U.S. government in May protesting the Air Force’s rocket development contracts awarded last year to SpaceX’s competitors.

Meanwhile, the Air Force has received bids from SpaceX, ULA, Blue Origin and Northrop Grumman for lucrative military contracts for as many as 34 launches between 2022 and 2026. The so-called “Phase 2” launch service procurement is the next stage in a multi-step, multi-year effort by the Air Force to select two contractors to cover the military’s future satellite launch needs, and end reliance on foreign-made rocket engines, such as those used by ULA’s Atlas 5 booster.

ULA and SpaceX currently launch most of the U.S. government’s military and intelligence-gathering satellites.

SpaceX said it was the only one of the four bidders to offer the Air Force a launch system that is currently flying, making the company the “lowest-risk solution” for the military’s most critical satellites. The Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets are already certified by the Air Force, and SpaceX indicated it planned to use the Falcon rocket family to compete for the Phase 2 launch service contracts.

ULA is developing the Vulcan-Centaur rocket to replace its Atlas and Delta rocket fleet. Blue Origin, founded by Amazon.com billionaire Jeff Bezos, is developing the New Glenn rocket, and Northrop Grumman is working on the new OmegA launcher.

While the ULA, Blue Origin and Northrop Grumman rockets are based on new designs, none look quite like the Starship.

Blue Origin is designing the first stage of its New Glenn rocket to land and be launched again, and ULA says it intends to eventually recover Vulcan main engines for reuse. But neither vehicle comes with the same lofty ambitions SpaceX has attached to the Starship.

A scaled-down version of the Starship with a single Raptor engine, called the Starhopper, completed a 500-foot (150-meter) test flight Aug. 27. The stubby three-legged vehicle, which space enthusiasts likened to a flying water tower, flew with a single Raptor engine, the most powerful rocket powerplant developed by SpaceX to date.

The Starhopper has been retired as a flight test vehicle in favor of the full-scale Starship.

About a mile down the road from the current location of SpaceX’s first Starship prototype, teams are readying launch and landing pads for the vehicle. Ground crews will transfer the Starship to the launch pad ahead of the first atmospheric test flight.

The Federal Aviation Administration, which is responsible for public safety during commercial rocket launches, will have to authorize the Starship’s test flights. It took several weeks for FAA safety analysts to issue a permit for the Starhopper’s test flight in August, and federal regulators ultimately only authorized a 150-meter top test, not the 200-meter flight SpaceX originally intended.

Musk characterized the delays caused by the FAA as “minimal.”

“I think the FAA asks good questions and wants to make sure things are safe, as do we,” he said. “So we’re going to make sure the risk to the public is vanishingly small, almost nothing, basically.”

The nearest residents to SpaceX’s South Texas test site live in a small housing subdivision called Boca Chica Village. SpaceX has distributed offers to homeowners in the neighborhood to buy their property for three times the appraised market value.

SpaceX broke ground on the privately-owned Boca Chica launch site in 2014 with the intention of launching Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets at the location, which sits just inland from the Gulf of Mexico, and just a couple of miles north of the U.S.-Mexico border.

“We are working with the residents of Boca Chica Village because we think, over time, it’s going to be quite disruptive to living in Boca Chica Village because it’ll end up needing to get cleared for safety a lot of time,” Musk said. “Probably not very comforting to Boca Chica Village. I mean, I think the actual danger to Boca Chica Village is low, but it’s not tiny. We want super tiny risks. Probably, over time, it would be better to buy out the villagers, and we’ve made an offer to that effect.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.