Rocket Lab’s third flight of the year delivered seven small commercial, military and educational satellites into orbit Saturday after a launch from New Zealand, while construction of a new launch pad in Virginia continues on pace for completion by the end of the year.

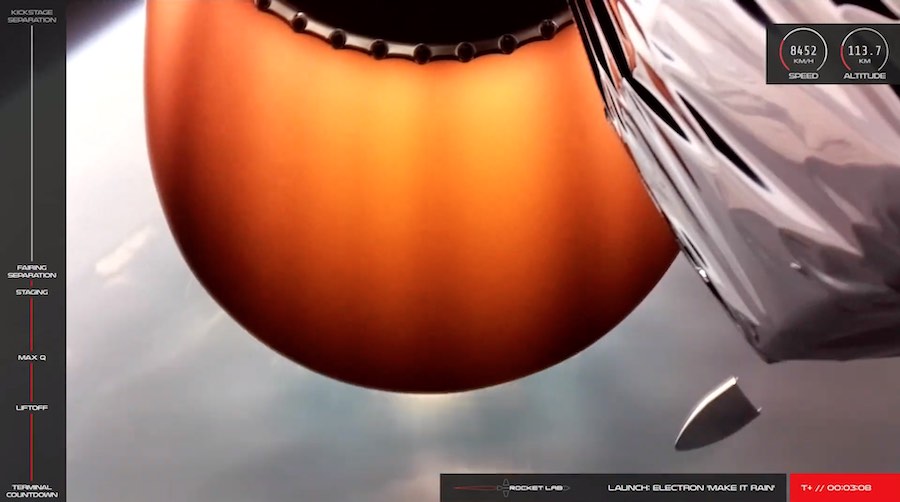

The 55-foot-tall (17-meter) Electron rocket fired nine kerosene-fueled Rutherford engines and climbed away from Rocket Lab’s Launch Complex 1 on Mahia Peninsula on New Zealand’s North Island at 0430 GMT (12:30 a.m. EDT) Saturday.

Liftoff occurred at 4:30 p.m. New Zealand time, shortly before sunset at Rocket Lab’s privately-operated launch base.

The commercial two-stage rocket, made of black carbon composite structures, pitched toward the east over the Pacific Ocean. A downward-facing camera showed Mahia Peninsula receding from view as the Electron rocketed into space with more than 40,000 pounds of thrust.

Two-and-a-half minutes into the mission, the Electron’s first stage shut down and jettisoned, and the rocket’s single Rutherford second stage engine ignited for a burn that lasted more than six minutes to reach a preliminary parking orbit.

Rocket Lab’s webcast streamed spectacular live video from cameras aboard the launch vehicle, but the live stream ended after the second stage completed its burn and released the Curie kick stage for the final phase of the flight.

The Curie kick stage, fueled by a “green” non-toxic fuel, was programmed to ignite around 50 minutes after liftoff for a 44-second firing intended to circularize the rocket’s orbit 280 miles (450 kilometers) above Earth, with an inclination of 45 degrees to the equator.

That maneuver apparently went off without a hitch. Peter Beck, Rocket Lab’s CEO, tweeted that all payloads — totaling around 176 pounds (80 kilograms) — deployed from the Curie kick stage, ending what he called a “perfect flight.”

Saturday’s mission, the seventh orbital launch attempt overall for Rocket Lab, was delayed two days to allow time for crews at Launch Complex 1 to replace faulty components on ground tracking equipment used to support the rocket’s flight termination system, which ground teams would activate to destroy the vehicle if it flew off course.

“That particularly system is getting quite old now,” Beck said. “We’re having more and more maintenance issues with it, and we are moving to an autonomous flight termination system here shortly, so it’s just a matter of keeping that equipment running,” Beck said in an interview with Spaceflight Now before the launch.

Rocket Lab’s first Electron launch in 2017 fell short of orbit after a ground tracking system lost a telemetry link with the rocket, prompting safety officials to send a destruct command to the vehicle. An investigation revealed the error was with the ground equipment, and the rocket itself was flying fine at the time of the destruct signal.

With Saturday’s flight, all six Electron missions since the failed first launch have been successful

“Giving our Flight 1 experience, we double and triple check that equipment every flight,” Beck said. “It’s not something we take risks with, so we replaced some hardware, and then we needed to run through a full set of verifications, and that all checked out.”

Saturday’s mission was nicknamed “Make it Rain” in a nod to the damp climate of Seattle, the home of Spaceflight, and at Rocket Lab’s launch site in New Zealand.

A glimpse of payload deployment from the Kick Stage for today's #MakeItRain mission for @SpaceflightInc. 🛰️ pic.twitter.com/Gp6DtkWuRa

— Rocket Lab (@RocketLab) June 29, 2019

The biggest payload on the next Electron launch was the BlackSky Global 3 Earth-imaging satellite — with a launch weight of approximately 123 pounds (56 kilograms) — set to join BlackSky’s first two commercial surveillance craft already in orbit after launches last year.

BlackSky is a business unit of Spaceflight Industries, which is also the parent company of Spaceflight, the rideshare launch broker.

Like the two BlackSky Global satellites currently in space, BlackSky’s third satellite will be capable of capturing up to 1,000 color images per day, with a resolution of about 3 feet (1 meter).

Last year, Spaceflight Industries announced a joint venture with Thales Alenia Space — named LeoStella — to build the next 20 BlackSky satellites in Tukwila, Washington, following the initial block of four smallsats, which includes the BlackSky Global 3 spacecraft launched Saturday.

BlackSky says its fleet of satellites will enable frequent revisits over the same location to help analysts identify changes over short time cycles. The company expects to have eight satellites in orbit by the end of the year, and aims to eventually field a constellation of up to 60 Earth-imaging spacecraft deployed.

One major customer for BlackSky could be the U.S. government. The National Reconnaissance Office, which owns the government’s spy satellite fleet, announced three study contracts earlier this month with BlackSky, Maxar Technologies and Planet to assess the usefulness of commercial imagery for U.S. intelligence agencies.

The launch also delivered two Prometheus CubeSats to low Earth orbit for U.S. Special Operations Command. The Prometheus smallsats are the latest in a series of CubeSats designed to test low-cost, easy-to-use communications relay technologies that could be used by special operations forces on combat missions.

According to information previously released by the military, the Prometheus spacecraft demonstrate the transmission of audio, video and data files from portable, low-profile, remotely-located field units to deployable ground station terminals using over-the-horizon satellite communications.

Two SpaceBEE CubeSats from Swarm Technologies, each weighing less than 2 pounds (1 kilogram), were also aboard the launch. The “BEE” in SpaceBEE stands for Basic Electronic Element.

Swarm is developing a low-data-rate satellite communications fleet the company says could be used by connected cars, remote environmental sensors, industrial farming operations, transportation, smart meters, and for text messaging in rural areas outside the range of terrestrial networks.

Swarm’s first four SpaceBEEs launched in January 2018 aboard an Indian Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle without approval from the Federal Communications Commission. After an investigation into the unlicensed launch — a first for the U.S. commercial satellite industry — the FCC fined Swarm $900,000 but allowed the launch of three more satellites on a Falcon 9 rocket in December.

The FCC raised concerns that the first four SpaceBEEs, each about the size of a sandwich, were too small to be reliably tracked by the military, which maintains a public catalog of objects in orbit. Like the satellites launching this month, the SpaceBEEs shot into orbit in December used a larger design based on a one-unit, or 1U, CubeSat standard.

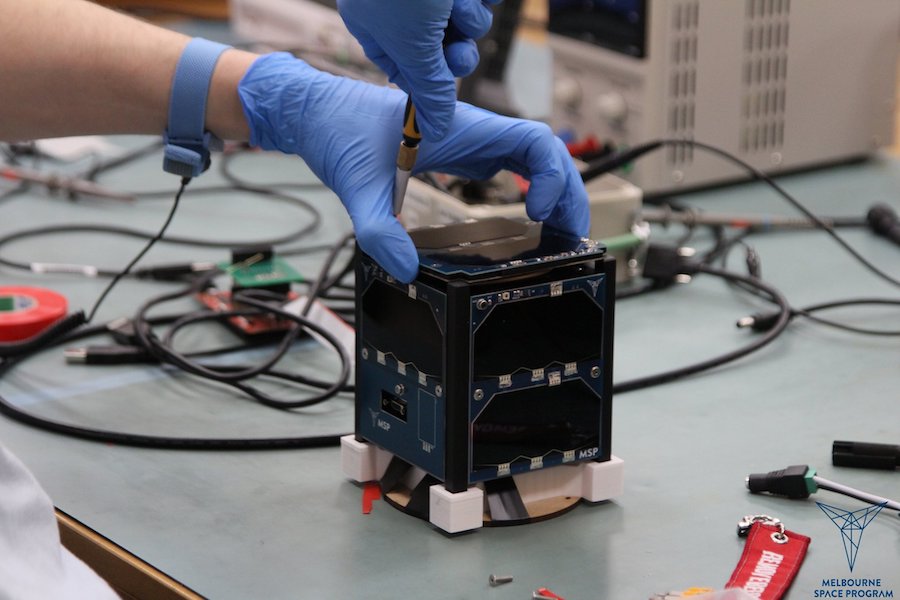

The ACRUX 1 CubeSat developed by the Melbourne Space Program, a non-profit educational organization affiliated with the University of Melbourne in Australia, also launched on the Electron rocket. Built by engineering students, ACRUX 1’s primary mission is education.

Australia’s first amateur satellite, Australis-OSCAR 5, was also built by students in Melbourne. Launched in 1970, it was the first amateur satellite designed and assembled outside North America.

“Since then, Australia’s satellite-related space capabilities have been stymied by outdated policies and regulation, hindering growth of the nation’s space industry and support of its incredible local talent,” members of the Melbourne Space Program wrote in an update on the organization’s website.

“In light of these challenges and obstacles, the Melbourne Space Program considers the design and build of ACRUX 1, as well as the successful securing of an international launch and related licenses, as significant accomplishments in themselves,” team members wrote on the group’s website.

The student engineers who developed the ACRUX 1 CubeSat say they will consider the mission fully successful if they receive a “ping” signal from the spacecraft. The ACRUX 1 team confirmed it received data packets from the CubeSat shortly after Saturday’s launch, verifying that the nanosatellite is alive in orbit.

“Receiving that ping from ACRUX 1 may seem like a modest mission goal, but the truth is far from it,” the team wrote before the launch. “That ping would mean ACRUX 1 has not only turned on in space, but has also communicated data back to us at our ground station in Greater Melbourne. In other words, it demonstrates that the satellite system built by our engineers actually works in space.”

A seventh satellite rode to space on the “Make it Rain” mission, but Spaceflight and Rocket Lab have not revealed its identity or owner.

Beck said it was the customer’s decision not to disclose the identity of the seventh payload on Saturday’s launch. The satellite’s purpose and owner coul be announced at a later date.

“There’s nothing incredible there,” Beck said. “Some customers have business propositions and business ideas that they’re trying to get to market first, just like every other industry. This is an example of that.”

He said the mystery satellite is not owned by Rocket Lab.

“It’s really up to the customer,” Beck said. “We’re providing the flight service. The customer has all the appropriate government approvals, so it’s purely a business decision.”

Construction pace at Virginia launch pad continues at “breakneck speed”

The construction of a new Rocket Lab launch pad in Virginia remains on a pace for the facility to be operational by the end of the year, Beck said.

The new launch pad, named Launch Complex 2, will look much like Rocket Lab’s existing facility in New Zealand. Launch Complex 2, or LC-2, is located at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport on Wallops Island, Virginia.

Rocket Lab announced Wallops as home of the company’s first U.S. launch site last October.

“There are not two days that look the same at LC-2,” Beck told Spaceflight Now. “The speed at which it’s being put together is truly impressive.

“For us sitting back here in New Zealand, we’re watching the might of the American machine and American scale at full pace,” he said. “There are rows of concrete trucks, the erector is fabricated and painted. It’s moving at breakneck speed and on schedule to be operational by the end of the year.”

The Electron launch pad at Wallops is, more or less, a “copy and paste” job from Launch Complex 1 in New Zealand, according to Beck. The layout and design of both pads will be much the same.

Teams in Virginia have updated some of the new pad’s design since construction began late last year. Rather than tapping into the kerosene and liquid oxygen supplies at a nearby launch pad used by Northrop Grumman’s Antares rocket, the new launch pad for the Electron rocket will have its own kerosene and liquid oxygen ground tanks.

“It turned out, because our vehicle is so small, we spend more liquid oxygen chilling in the large pipes that are designed for Antares than we actually use the vehicle,” Beck said. “So it becomes economically silly to take these large 4 inch pipes and chill them all in to provide a 2-inch pipe into an Electron. It made a whole lot more sense to just put the right size tank there to supply the vehicle.”

The chilling procedure involves pumping small quantities of cryogenic fluids through ground system and rocket plumbing, helping ease the thermal shock before propellant loading begins.

Beck said Rocket Lab is also going with its own kerosene, or RP-1, fuel farm at Launch Complex 2, rather than rely on the tanks at the nearby Antares launch pad.

“It’d be more work to interface with the RP-1 from Antares than us just creating our own system,” Beck said.

Rocket Lab is headquartered in Huntington Beach, California, and operates two factories.

One factory in Auckland produces composite structures for the Electron rocket, and is home to the company’s primary control center. Rocket Lab’s Huntington Beach plant builds engines and avionics.

Rocket Lab has not announced a payload for the first Electron launch from U.S. soil, but the company has said the facility will be tailored for government customers. The new launch pad in Virginia will be capable of supporting up to 12 launches per year, Rocket Lab officials said.

Meanwhile, launch campaigns will continue in New Zealand, which will remain Rocket Lab’s primary launch site, according to company officials.

The next Electron launch is scheduled for August carrying another batch of small satellites into orbit on a rideshare mission arranged directly by Rocket Lab, rather than through a third-party broker, Beck said.

By the end of the year, Beck said Rocket Lab should achieve a cadence of monthly launches.

“We got a little bit of a slow start at the beginning of the year, so we’re trying to play catch up,” Beck said. “So somewhere between eight and 10, I would say, will be where we get to, but it really depends on a couple of things. How quickly we can continue to scale and turn around the launch vehicles? We’ve also got a couple of really major projects later this year with LC-2 coming online in Virginia, and a couple of R&D (research and development) projects we’ll be announcing in the later half of this year.

“People will see what we’re up to,” he said. “It’s a very busy time.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.