Scientists marked the 10th anniversary of the launch of NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter on Tuesday, celebrating a mission that has greatly outlived its original one-year design life and continues taking high-resolution pictures to help U.S. companies and international space agencies select destinations for moon landers.

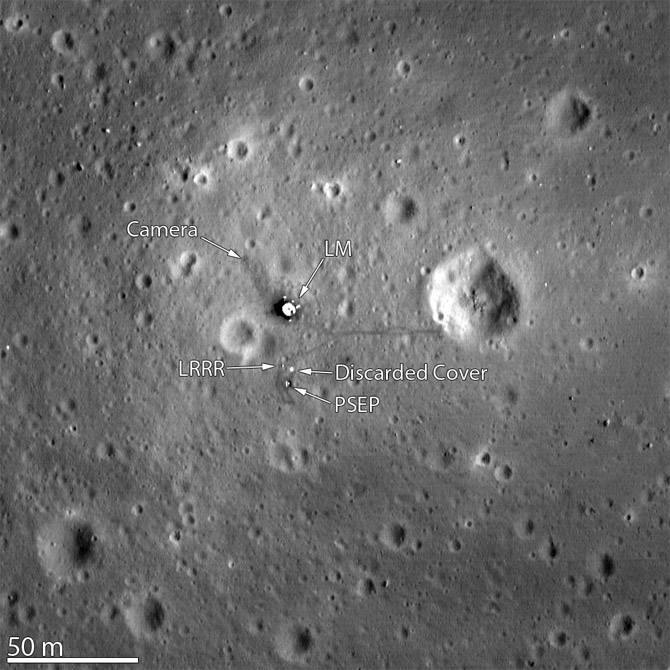

LRO launched June 18, 2009, from Cape Canaveral aboard a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket and arrived in lunar orbit four-and-a-half days later. By mid-July of that year, the orbiter’s sharp-eyed camera captured the first detailed views of the Apollo landing sites in time for the 40th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission.

In its 10-year mission, LRO has contributed to new discoveries of water and other volatile molecules on the moon, located fresh lunar impact craters, and found that the moon was contracting in its recent history, and may still be shrinking today, due to the cooling of lunar interior.

“The great strides that we’ve made in understanding the volatile inventory on the moon, beginning to understand the volatile cycle on the moon, and beginning to understand the volcanic history of the moon is something that we’ve made incredible contributions to,” said Noah Petro, LRO’s project scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland.

“The moon is an extension of the Earth,” Petro said. “I like to think of the moon as the eighth continent of the Earth, and when we study the moon, we learn about the ancient history of the solar system, as well as the current history of the solr system.”

LRO is still operating, and all seven of its instruments are still collecting data, Petro said. There’s enough propellant left on LRO to continue the mission for at least seven more years, based on the current rate of fuel consumption, he said.

NASA officials expect LRO to live up to its “reconnaissance” function into the 2020s, providing maps for robotic lunar landers and helping identify sites where humans could safely return to the moon’s surface.

“The spacecraft is remarkably healthy,” Petro said. “Ever since about 2011, we’ve been in a very … fuel-efficient orbit, so we’ve basically been able to save our fuel for the last seven or eight years now. That has really given us the ability to continue operating.

“Some systems are showing signs of age, but that is what engineers love to try to solve … and they’ve been able to figure out a way to keep it going.”

The transmitter on LRO’s radar instrument failed in 2011, but ground teams devised a way to use ground-based radars coupled with the still-functioning receiver on LRO to image the moon in search of water ice deposits. Last year, engineers determined LRO’s inertial measurement unit was nearing the end of its life.

The unit measures the spacecraft’s rotation rates, and ground teams are using LRO’s star tracker cameras to derive an estimate of the orbiter’s rotation, reserving the rest of the inertial measurement unit’s lifetime for critical events such as emergencies and eclipses.

“I hesitate to talk about the legacy of a mission that’s still ongoing,” Petro said in an interview Tuesday with Spaceflight Now.

LRO is currently circling the moon in an elliptical orbit, ranging from a low point about 30 miles (50 kilometers) over the moon’s south pole and a high point around 110 miles (180 kilometers) over the lunar north pole, Petro said.

Over the next few years, the spacecraft’s orbit will naturally change, due to gravitational perturbations, to a circular orbit at an altitude of about 60 miles (100 kilometers), according to Petro.

LRO was developed during NASA’s Constellation program, which started during the George W. Bush administration with a goal of returning humans to the moon by 2020. The program fell years behind schedule and its costs rose by billions of dollars, prompting President Barack Obama to cancel the program in 2010, a year after LRO’s launch.

The Obama administration, with the urging of lawmakers in Congress, directed NASA to focus on a human mission to Mars. The Orion crew capsule, a holdover from the Constellation program, and the new heavy-lift Space Launch System rocket became the centerpieces of NASA’s deep space exploration program.

President Donald Trump in 2017 signed a directive tasking NASA with returning humans to the lunar surface. In a speech in March, Vice President Mike Pence set a 2024 deadline for a human landing on the moon, an accelerated schedule that NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine told CNN last week would require an extra $20 billion to $30 billion to the agency’s budget over the next five years.

NASA announced contracts last month with three U.S. companies — Astrobotic, Intuitive Machines and Orbit Beyond — to fly experiments to the moon in 2020 and 2021. The commercial robotic probes are precursors before an eventual landing with astronauts.

LRO will provide maps for the companies in charge of the commercial landing probes.

“We’ve been scouting landing sites for all 10 years,” Petro said. “Initially, that was one of LRO’s primary objectives, was to find safe landing sites, and as missions were conceived and developed, requests would be made to (NASA) Headquarters, and to us, to make observations to find safe and interesting landing sites.”

LRO has also aided international lunar missions. Chinese scientists planning the Chang’e 3 and Chang’e 4 lunar landing missions used LRO’s maps, and the NASA orbiter imaged the Chang’e 4 spacecraft on the far side of the moon after its arrival there earlier this year.

India’s Chandrayaan 2 mission is set to become the next spacecraft to land on the moon. Its launch is scheduled for July 14, followed by a landing near the moon’s south pole in September.

“We’ve been collecting data for a number of international missions, including Chandrayaan 2, and when that data is collected it’s processed and made available to everyone,” Petro said.

“Once they land, we’ll be able to image the location of the lander and provide context for their measurements,” Petro said of Chandrayaan 2.

“My personal goal is to have LRO operate long enough to see not just one, but many, U.S. missions to the lunar surface, so getting these commercial landers there is going to be the first part of that dream of mine,” Petro said.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.