Boeing engineers have completed hotfire testing on a flight-like model of the Starliner crew capsule, clearing a major hurdle before a pad abort test and a demonstration flight to the International Space Station later this summer, Boeing announced Friday.

The service module hotfire testing at NASA’s White Sands Test Facility in New Mexico wraps up a key phase of Starliner’s development. During an earlier round of service module checkouts last June, valves in the craft’s abort engines failed to fully close after a brief burn, resulting in a propellant leak on the test stand at White Sands.

Boeing halted propulsion testing after the accident, and engineers implemented hardware and software fixes to resolve the valve problem, according to remarks last fall by Chris Ferguson, a Boeing test pilot and former NASA astronaut who will fly on the ship’s first piloted demonstration mission to the space station.

After making the changes, Boeing restarted the service module hotfire testing.

“With the safety of our astronauts at the forefront of all we do, this successful testing proves this system will work correctly and keep Starliner and the crew safe through all phases of flight,” said John Mulholland, vice president and program manager of Boeing’s commercial crew program, in a statement. “The milestone paves the way for the upcoming pad abort test and flights to and from the International Space Station later this year.”

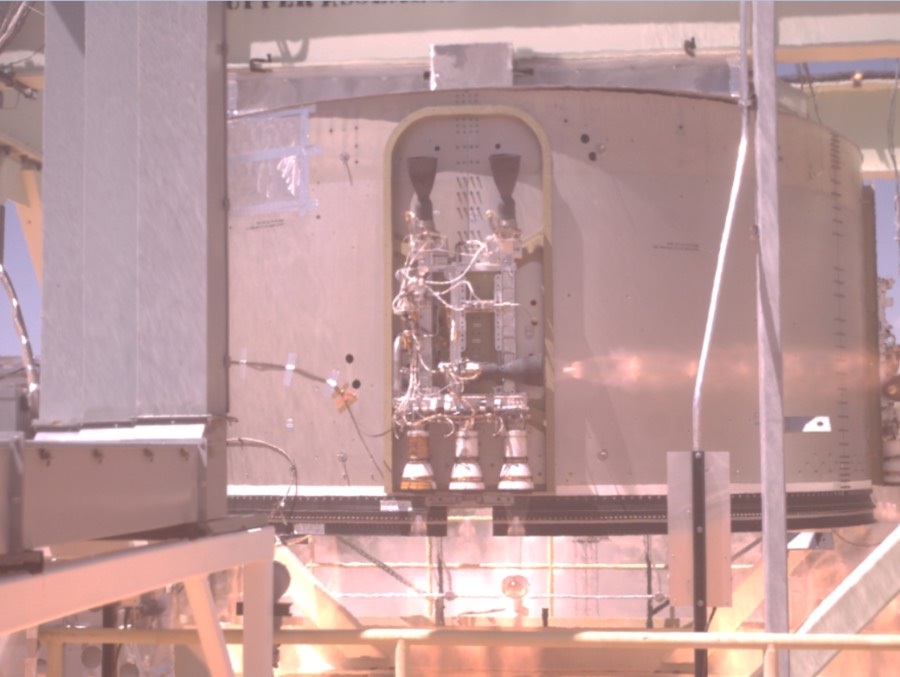

Boeing said in a statement that teams ran multiple tests on the service module, which will fly into space attached to the rear of the componay’s CST-100 Starliner crew compartment. The service module contains the spacecraft’s thrusters for a launch abort and in-space maneuvers.

At the end of each mission, the Starliner will jettison the service module to burn up during re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere. The crew module will descend under parachutes for an airbag-cushioned landing at one of several candidate sites in the Western United States.

The service module test rig used in the recent hotfire testing included fuel and helium tanks, reaction control system, orbital maneuvering and attitude control thrusters, launch abort engines, and all necessary fuel lines and avionics, according to Boeing.

During the testing at White Sands, Boeing says the Starliner’s service most test article fired 19 thrusters to simulate in-space maneuvers, 12 thrusters to simulate a high-altitude abort from its launch vehicle, and 22 propulsion elements — including four high-power abort engines — to simulate a launch escape maneuver at low altitude.

Each Starliner service module carries four launch abort engines, built by Aerojet Rocketdyne. The engines would only fire in flight in the event of a launch emergency, igniting with 40,000 pounds of thrust each for a few seconds to propel the capsule away from its rocket.

The four launch abort engines are joined by 48 smaller thrusters on the CST-100 service module, including a set of 1,500-pound-thrust orbital maneuvering and attitude control engines used for pointing during a launch abort and for large orbital maneuvers, and pods of 100-pound reaction control thrusters, all manufactured by Aerojet Rocketdyne.

In April, when Boeing announced its most recent schedule for the Starliner’s test flights, the company planned a pad abort test at White Sands this summer. The pad abort will prove the capsule’s ability to quickly fire off the top of its launcher in the event of an emergency on the launch pad.

As of last month, Boeing planned to conduct the pad abort test before the Starliner’s first space mission which is scheduled for August, according to Rebecca Regan, a Boeing spokesperson.

The Starliner’s first space mission is called the Orbital Flight Test. The test flight will include a docking with the space station, followed by a landing in the Western United States.

The Orbital Flight Test’s liftoff from Cape Canaveral on a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket is scheduled for Aug. 17. Assuming that launch date, liftoff would occur at approximately 9 a.m. EDT (1300 GMT), a time determined by the space station’s orbit.

If that mission goes well, Boeing could be ready to fly the Starliner’s Crew Flight Test to the space station as soon as November with Boeing test pilot Chris Ferguson and NASA astronauts Mike Fincke and Nicole Mann on-board.

Ferguson, Fincke and Mann will spend several months on the orbiting outpost as part of an expanded space station crew.

On Thursday, ULA shipped the completed Atlas 5 first stage and dual-engine Centaur upper stage assigned to the Starliner’s first crewed mission. The rocket stages are riding ULA’s Mariner transport ship from ULA’s factory in Decatur, Alabama, via river and sea to Port Canaveral, where the hardware is due to arrive in early June.

The Atlas 5 rocket for the Orbital Flight Test arrived at Cape Canaveral last October.

Once the test flights are complete, the Starliner should be ready to begin regular crew rotation flights to the station under contract to NASA, with four astronauts on each mission.

NASA has awarded Boeing a series of contracts and agreements since 2010 — worth a combined $4.8 billion — to fund development of the CST-100 Starliner spacecraft.

The space agency has awarded a set of similar contracts to SpaceX worth more than $3.1 billion for that company’s Crew Dragon capsule, which completed its first unpiloted demonstration flight to the space station in March.

SpaceX planned to conduct its first piloted space mission, with two NASA astronauts aboard another Crew Dragon capsule, as soon as late September. But that was before the Crew Dragon that returned from the station in March exploded on the ground during an abort engine hotfire test at Cape Canaveral on April 20.

SpaceX and NASA have not announced any results from the investigation into the April 20 Crew Dragon accident.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.