EDITOR’S NOTE: Updated April 3 with NASA’s confirmation of an extension to the duration of the Crew Flight Test and SpaceX statement on Crew Dragon schedule.

Boeing said Tuesday the first orbital test flight of its commercial crew capsule, named the Starliner, will be delayed until August “in order to avoid unnecessary schedule pressure” and give priority on the Atlas 5 rocket’s manifest to a U.S. Air Force communications satellite. NASA confirmed Wednesday that officials have approved an extension of the Starliner’s first crewed mission to last up to several months.

A statement issued by Boeing on Tuesday confirmed previous reports that the company’s CST-100 Starliner spacecraft, designed and built under a $4.2 billion contract from NASA, would miss its previous target launch date for an unpiloted test flight to the International Space Station in April. NASA and industry sources have said for months that an April launch date was not feasible, but NASA and Boeing had not officially published a revised schedule since early February.

The first Starliner test flight with astronauts on-board was previously scheduled for August. In Boeing’s schedule update released Tuesday, the company only said it expects the Crew Flight Test to occur “later this year,” but sources said the Starliner could fly with astronauts in November, at the earliest.

NASA said Wednesday that the Crew Flight Test’s duration has been extended, as officials previously said was possible. The Starliner’s first test flight with astronauts was originally supposed to last no more than a couple of weeks, but the crew could now remain aboard the space station for months. The exact duration of the Crew Flight Test will be determined at a later date, NASA said.

“NASA’s assessment of extending the mission was found to be technically achievable without compromising the safety of the crew,” said Phil McAlister, director of the commercial spaceflight division at NASA Headquarters. “Commercial crew flight tests, along with the additional Soyuz opportunities, help us transition with greater flexibility to our next-generation commercial systems under the Commercial Crew Program.”

The Crew Flight Test mission extension will allow the space station crew to conduct additional research and maintenance, helping ensure the U.S. segment of the orbiting outpost remains fully staffed as NASA transitions from exclusively using Russian Soyuz crew capsules to using a mix of SpaceX, Boeing and Russian vehicles for astronaut transportation.

A hotfire test of the Starliner’s abort engines, delayed from last year after a fuel leak on the test stand at NASA’s White Sands Test Facility in New Mexico, is planned in the coming months. That will be followed by a pad abort test at White Sands in the summer timeframe, before the Starliner’s first space mission, according to Rebecca Regan, a Boeing spokesperson.

The pad abort test will verify the Starliner’s four liquid-fueled escape engines can send the capsule and the astronauts on-board away from a failing rocket. The pad abort test was previously scheduled between the Starliner’s first orbital mission, designated the Orbital Flight Test, and the capsule’s first crewed mission. Earlier in the spacecraft’s development, Boeing originally aimed to conduct the pad abort test before both test flights to the space station, but officials shuffled the sequence after last year’s hotfire test anomaly.

With the updated schedule released Tuesday, the Starliner’s Orbital Flight Test will be leapfrogged in United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket’s manifest at Cape Canaveral by the Air Force’s fifth Advanced Extremely High Frequency communications satellite, which has held to a target launch date of June 27 for several months. Boeing said the Starliner’s Orbital Flight Test had a narrow launch opportunity in the first week of May to clear the Atlas 5’s launch pad at Cape Canaveral before the AEHF 5 mission.

“In order to avoid unnecessary schedule pressure, not interfere with a critical national security payload, and allow appropriate schedule margin to ensure the Boeing, United Launch Alliance and NASA teams are able to perform a successful first launch of Starliner, we made the most responsible decision available to us and will be ready for the next launch pad availability in August, while still allowing for a Crew Flight Test later this year,” Boeing said in a statement.

Boeing test pilot Chris Ferguson, a former NASA astronaut who commanded the last space shuttle mission in 2011, will be joined by NASA crewmates Mike Fincke and Nicole Mann on the Crew Flight Test mission.

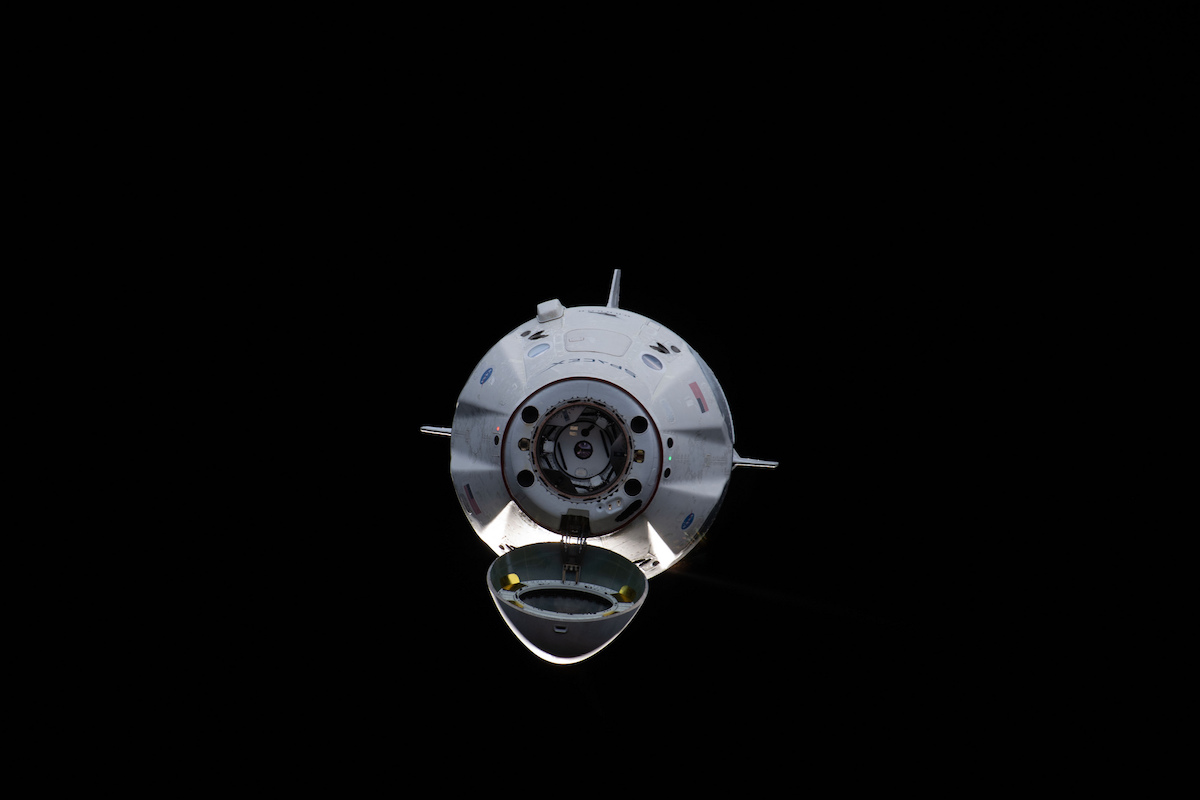

Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner is one of two commercially-developed crew capsules funded by NASA to ferry astronauts to and from the space station. SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft launched March 2 on a six-day test flight to the space station, demonstrating its capabilities before a second test as soon as July with NASA astronauts Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley on-board.

The Crew Dragon capsule returned to Earth under parachutes March 8 for a splashdown in the Atlantic Ocean.

NASA said Wednesday that officials “are expected to reevaluate (the Crew Dragon’s) target test dates in the next couple weeks.”

A SpaceX spokesperson said Wednesday that the company is “on track for a test of Crew Dragon’s in-flight abort capabilities in June and hardware readiness for Crew Dragon’s second demonstration mission to the space station in July.”

While SpaceX’s Crew Dragon launches on top of the company’s Falcon 9 rocket and returns to splashdowns at sea, the CST-100 Starliner will take off aboard Atlas 5 rockets built by United Launch Alliance, a 50-50 joint venture between Boeing and Lockheed Martin. At the end of each mission, the Starliner will parachute back to Earth for a landing in the Western United States.

SpaceX originally intended to reuse the Crew Dragon for multiple missions to the space station, but officials have dropped that plan, at least for now, after redesigning the capsule for ocean landings. Boeing says each CST-100 crew capsule can fly in space up to 10 times.

After they complete their test flights, the Crew Dragon and CST-100 Starliner spaceships will begin regular crew rotation flights to the space station, where they will stay docked as emergency lifeboats for up to 210 days before returning astronauts to Earth.

Boeing said Tuesday the Starliner program continues to make progress. The company said it recently cleared the last major test milestones ahead of the unpiloted demonstration flight to the space station, and technicians are “entering the final phases of production” on the Orbital Flight Test vehicle.

Nevertheless, Boeing said the delay to August for the Starliner’s first space mission allows teams to “take the necessary time to ensure this critical flight will be successful and prove our reusable vehicles will be ready to fly multiple long-duration missions throughout the lifetime of the International Space Station.”

The Starliner team recently completed two parachute drop tests, and one of the human-rated Starliner spaceships recently finished a series of environmental tests at Boeing’s satellite factory in El Segundo, California, officials said. Engineers also conducted a “range of motion” test on the Starliner’s docking adapter, which will connect the capsule to the space station.

Boeing is building the CST-100 Starliner capsules in a repurposed space shuttle hangar at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, where the company also plans to refurbish the spacecraft between missions. The company plans to initially build two full-up Starliner capsules for crew rotation flights to the space station, designated Spacecraft 2 and Spacecraft 3.

Spacecraft 1, the first of the line, will be used on the pad abort test in New Mexico.

The capsule used for environmental testing in El Segundo was Spacecraft 2. The battery of environmental tests subjected the spacecraft to the extremely hot and cold temperatures, vacuum conditions, electromagnetic radiation, and the vibration and acoustic environments it will encounter in flight. With that testing completed, the capsule will be shipped back to the Kennedy Space Center for final outfitting ahead of the Crew Flight Test.

Boeing is assembling Spacecraft 3 for the Orbital Flight Test.

The fuel leak in the Starliner’s abort engines last June led to months of delays in the program, while engineers in parallel studied issues with the Boeing capsule’s parachutes and pyrotechnic systems. The delays ultimately led Boeing to fall months behind SpaceX in launching their crew capsule’s first unpiloted space mission.

“Both Boeing and SpaceX are working through very different issues related to their propulsion systems, and in addition both providers are continuing to refine, set and understand their parachute designs,” said Sandy Magnus, a former NASA astronaut, during a meeting of NASA’s Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel on March 7. “It’s a critical safety design element that is an ongoing challenge for both.”

Boeing said the company is nearing the finish line in overcoming the propulsion and parachute challenges.

“With environmental testing complete, we now need only one more parachute qualification test, the service module hot fire test and a pad abort test before we are fully qualified to fly our Crew Flight Test,” Boeing said. “None of those tests are necessary ahead of the uncrewed Orbital Flight Test.”

NASA said new launch abort engine valves, redesigned after malfunctioning and causing the propellant leak after a hotfire test last year, have been manufactured and are being installed on the Starliner’s test abort engines, built by Aerojet Rocketdyne. The next set of new hardware will soon be installed in the pad abort service module, NASA said.

Boeing said its team wants to fly a crew-ready spacecraft on the unpiloted test.

“It is most important to us to fly a complete vehicle and collect as high-fidelity data as we can from these crucial flight tests before we turn the vehicles around and prepare them for regular long-duration missions,” the company said in a statement.

SpaceX tested Crew Dragon’s abort system during an on-pad test in 2015, demonstrating the ship’s SuperDraco escape thrusters have the power to drive the spacecraft off its rocket sitting on the ground in the event of an accident during the countdown. An in-flight abort test is planned this summer, before the Crew Dragon’s first mission with astronauts, to evaluate the capsule’s ability to escape a rocket at high altitude.

Unlike the pad escape demonstration, an in-flight abort test was not required by NASA of either company, and Boeing elected to forego it.

The Crew Dragon that flew to the space station last month launched with much of the spaceship’s life support system, including air revitalization equipment to regulate oxygen and carbon dioxide inside the spaceship. The crew seats and display monitors also flew, but the displays were not activated and functional, according to Hans Koenigsmann, SpaceX’s vice president of build and flight reliability.

The touch-screen crew controls, push buttons and the toilet will be added to the next Crew Dragon vehicle for astronauts.

SpaceX also plans to add heaters to the Crew Dragon’s propulsion system to keep propellants from getting too cold, which could cause a shock or vibration that could damage the capsule’s Draco control thrusters.

Speaking at the safety panel meeting last month, Magnus said SpaceX and Boeing are pursuing different plans for their test flights.

“It is not possible to do a direct comparison of the two uncrewed flights and the milestones that they’re performing,” Magnus said. “They’re different for different reasons for each provider. Each provider has targeted different objectives, and it’s based on their operations concept and their design philosophy.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.