United Launch Alliance placed a new satellite in orbit with a fiery Friday night blastoff from Cape Canaveral, using a version of the Delta 4 rocket that is nearing retirement to supplement a U.S. military network relaying signals from drones and battlefield commanders.

After ground teams cleared several technical hurdles with the rocket and a satellite tracking network, the 218-foot-tall (66-meter) Delta 4 launcher’s hydrogen-fueled RS-68A main engine flashed to life with an orange burst of flame moments before liftoff.

Five seconds later, four solid rocket motors ignited, and hold-down bolts released at 8:26 p.m. EDT Friday (0026 GMT Saturday) as the Delta 4 rapidly climbed away from Cape Canaveral’s Complex 37B launch pad with 1.8 million pounds of thrust.

The main engine and booster nozzles vectored their thrust to guide the Delta 4 east over the Atlantic Ocean, sending the U.S. Air Force’s tenth Wideband Global SATCOM communications satellite toward its final operating position more than 22,000 miles (nearly 36,000 kilometers) over the equator in geostationary orbit.

The Delta 4’s solid rocket boosters, built by Northrop Grumman, burned out and jettisoned in two pairs around 1 minute, 40 seconds, into the mission. Once above the dense lower layers of the atmosphere, the Delta 4 released its nose cone to reveal the WGS 10 satellite.

The Aerojet Rocketdyne RS-68A main engine fired nearly four minutes until the first stage released to fall into the Atlantic Ocean. An upper stage RL10B-2 engine, also supplied by Aerojet Rocketdyne, ignited two times to loft the WGS 10 spacecraft into an elliptical transfer orbit ranging as high as 27,500 miles (44,300 kilometers) above Earth.

The Boeing-built WGS 10 satellite separated from the Delta 4’s upper stage at T+plus 36 minutes, 50 seconds, extending the company’s streak of successful missions to 133 since its formation in 2006.

Friday night’s launch was delayed 90 minutes to allow time for engineers to examine technical concerns on the first and second stages of the Delta 4 rocket. Once those issues were cleared, the launch team had to wait for officials to ensure NASA’s Tracking and Data Relay Satellite System was ready to route telemetry from the rocket to ground controllers.

The mission marked the next-to-last flight of the Delta 4 rocket variant with a single first stage core — known as the Delta 4-Medium — as ULA begins retiring segments of its launcher family in preparation for the debut of the new Vulcan booster, which the company says will be less expensive than the existing Atlas and Delta fleet.

Gary Wentz, ULA’s vice president of government and commercial programs, said the company’s decision in 2014 to retire the Delta 4-Medium was intended to reduce the company’s costs.

“We started looking at the products that we were providing, and found that maintaining these two families of launch vehicles, both the Delta and the Atlas, through this period decreased our flight rate, and therefore increased our costs,” Wentz said. “That really drove it, based on the competitive industry we’re in, trying to maximize our competitiveness.”

The Delta 4-Medium family provides the same range of lift capability as the less expensive Atlas 5 rocket. The Delta 4-Heavy, which will remain operational through at least the early-to-mid-2020s, uses three Delta 4 first stage cores bolted together to haul heavier payloads to orbit than any of the Atlas 5 configurations.

ULA was formed in 2006 by the merger of Boeing’s Delta 4 and Lockheed Martin’s Atlas 5 rocket programs. The 50-50 joint venture kept both rocket lines operational to ensure the U.S. military had two independent launch options for national security satellites.

But SpaceX’s Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets are now certified to launch U.S. national security payloads. With the Falcon and Atlas rocket families, the military will continue to have two launch options after the Delta 4-Medium’s retirement.

Friday’s launch used the Delta 4-Medium+ 5,4 rocket variant, with four solid rocket boosters and a 5.1-meter (16.7-foot) upper stage and payload shroud. It was the eighth and final flight of the Delta 4-Medium+ 5,4 configuration, and all carried WGS satellites for the Air Force.

One more Delta 4-Medium rocket is set for launch July 25 from Cape Canaveral with an Air Force GPS navigation satellite. That launcher will fly in the Delta 4-Medium+ 4,2 configuration, with two solid rocket boosters and a 4-meter (13.1-foot) diameter upper stage and payload fairing.

With Friday’s launch, the Delta 4 rocket has flown 39 times since November 2002, and 28 of those missions used a Delta 4-Medium.

“It’s had a very successful history, and it’s similar to the WGS satellite, it’s a workhorse for the Air Force,” Wentz said of the Delta 4-Medium. “It’s kind of bittersweet that we’re here at the end, but we look forward to the missions to come in the future, and the vehicles that we’ll field.”

Including the GPS launch in July, ULA has contracts in place for six Delta 4 flights through 2024. The five Delta 4-Heavy launches planned in the early 2020s will all hoist top secret payloads for the National Reconnaissance Office, the U.S. government’s spy satellite agency:

- Delta 4-Medium+ 4,2 with the GPS 3 SV02 payload

- Launch Date: July 25, 2019

- Launch Site: SLC-37B, Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida

- Delta 4-Heavy with the NROL-44 payload

- Launch Date: 2020

- Launch Site: SLC-37B, Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida

- Delta 4-Heavy with the NROL-82 payload

- Launch Date: 2020

- Launch Site: SLC-6, Vandenberg Air Force Base, California

- Delta 4-Heavy with the NROL-91 payload

- Launch Date: Fiscal year 2022

- Launch Site: SLC-6, Vandenberg Air Force Base, California

- Delta 4-Heavy with the NROL-68 payload

- Launch Date: Fiscal year 2023

- Launch Site: SLC-37B, Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida

- Delta 4-Heavy with the NROL-70 payload

- Launch Date: Fiscal year 2024

- Launch Site: SLC-37B, Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida

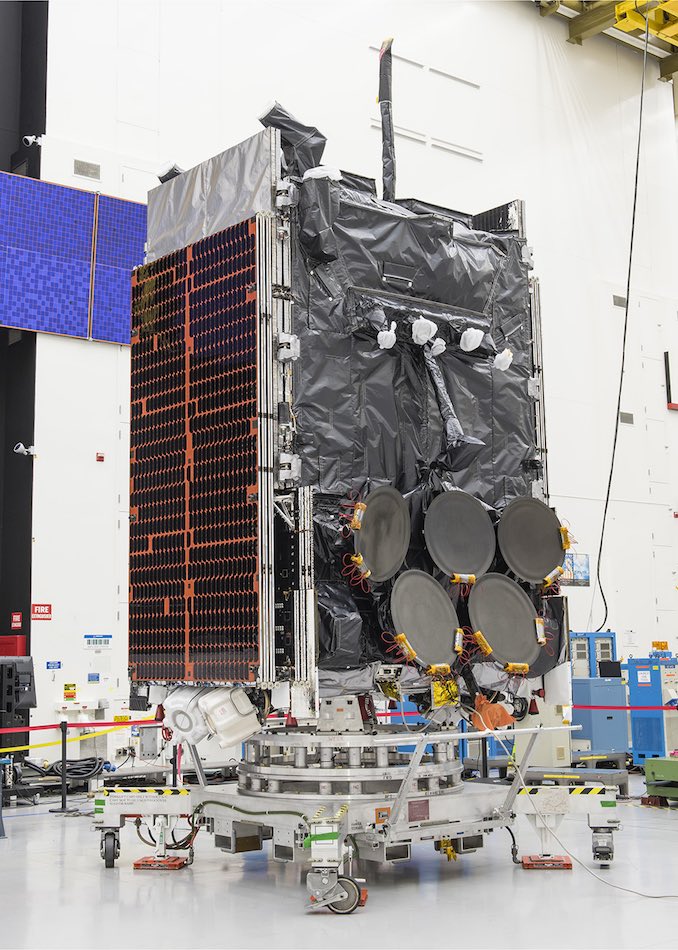

The 13,200-pound (6,000-kilogram) WGS 10 communications satellite launched Friday night joins nine broadband satellites deployed since 2007 to form a globe-spanning network relaying video, data and other information between the battlefield to decision makers.

The WGS fleet transmits classified and unclassified signals, supporting U.S and allied forces around the world. Featuring a digital channelizer, the roughly $400 million WGS 10 satellite will relay high-data-rate communications in X-band and Ka-band frequencies during a mission expected to last at least 14 years.

“WGS has the unique ability to cross-band between military Ka- and X-band, which provides our warfighters significant flexibility to maximize communications capability,” said Tom Becht, director of the military satellite communications directorate at the Air Force’s Space and Missile Systems Center in Los Angeles.

The nine previous WGS satellites all launched on ULA rockets — the first two on Atlas 5s in 2007 and 2009, and the following seven on Delta 4s. The Wideband Global SATCOM fleet is the U.S. Defense Department’s highest capacity satellite communications network.

Two of the 10 WGS satellites launched to date were funded by international governments. WGS 6 was funded by Australia, and a consortium including Canada, Denmark, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and New Zealand paid for the WGS 9 satellite launched in March 2017. In exchange for their contributions, those nations’ militaries gain access to the WGS network.

WGS 10 is the fourth and final “Block II Follow-On” WGS satellite, and it’s the third with the digital channelizer, which handles communications signals more efficiently, nearly doubling the bandwidth provided by earlier spacecraft in the series.

Based on the Boeing 702 satellite platform, WGS 10 will use a liquid-fueled boost engine and plasma thrusters to circularize its orbit more than 22,000 miles over the equator. The maneuvers will take about four months, officials said, before WGS 10 reaches geostationary orbit, where its velocity will match the rate of Earth’s rotation.

After a two-month test campaign in geostationary orbit over the United States, military leaders will decide where to deploy WGS 10.

Army Col. Enrique Costas, project manager for defense communications and Army transmission systems, said the WGS network is widely-used in the military because of its reliability and high-bandwidth capacity, enabling live video transmissions from drones around the world back to operators hundreds or thousands of miles away.

“If I was to target a specific terrorist in the Middle East, and I have an ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance) platform that is looking at that terrorist, I need to be able to make a decision whether or not to fire, or send a ground team to get that target,” Costas said.

High-resolution video streaming from a flying drone requires a lot of bandwidth, he said.

“I need to be able to transmit that signal from the point of collection all the way back to the center where the decision is going to be made whether to not to pull the trigger or deploy a team to act upon a specific mission,” Costas told reporters in a pre-launch conference call. “WGS is one of the primary ISR carriers for operational workforce in some theaters.”

The White House and State Department also rely on WGS satellites, and the network broadcasts TV signals to troops stationed around the world.

“If … I have a telecon between the (combatant commander) and the president of the United States, I want to make sure that the signal doesn’t go down at any time during that conversation to make critical decisions,” Costas continued. “WGS is part of that transport to make sure that we have reliable and assured communications regardless of where we are on the planet.”

The Air Force is close to awarding a new contract to Boeing for at least one additional WGS satellite.

Congress added $600 million to the fiscal year 2018 defense budget for two new WGS satellites, overruling the military’s plans to begin sourcing more communications capacity from commercial satellites. But the funding line included no money to launch the satellites, each of which costs between $300 million and $400 million.

The Air Force has kicked off another round of WGS procurement using the unexpected money, and Boeing submitted a proposal in January. Military officials have not decided whether to order one or two more WGS satellites, according to Becht. He said a final decision and contract signature is expected later this year.

Becht said the Air Force could follow a purchasing model often used by commercial satellite operators, in which Boeing would be responsible for building the new WGS spacecraft using more cost-effective practices. Boeing could also select a launch provider for the new WGS spacecraft, bundling the entire mission into one turnkey contract, with final delivery of the satellite to the Air Force after it is in orbit.

“The capabilities of the WGS system are supporting our allies around the world in joint missions, and helping our military to be more effective,” said Rico Attanasio, Boeing’s director of tactical communications. “Moving forward, as the need for resilience in SATCOM grows, I’m confident WGS will continue to be a key element in meeting the needs of assured protected communications.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.