Images taken by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft when it flew by an object the size of a large metropolitan area at the frontier of the solar system Jan. 1 have revealed the miniature world has a more flattened shape than the flyby’s initial pictures suggested.

The oddly-shaped object in the Kuiper Belt, located a billion miles (1.6 billion kilometers) beyond Pluto, became the most distant planetary body ever explored when the New Horizons spacecraft zipped by Jan. 1 at a relative velocity of roughly 32,000 mph, or 9 miles per second (14 kilometers per second).

Nicknamed Ultima Thule, the New Horizons spacecraft’s first target after visiting Pluto in 2015 was revealed to be a dual-lobed object as the probe beamed its first close-up images back to Earth after the New Year’s Day encounter.

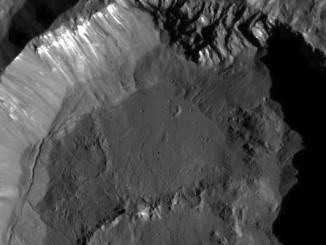

But instead of having the shape of a snowman — with one spherical lobe larger than the other — scientists now believe Ultima Thule’s two sections have a more flattened shape.

The larger of the two lobes — nicknamed Ultima — appears to be shaped like a giant pancake, or a pebble that could be thrown to skip across water. The smaller lobe, nicknamed Thule, resembles a dented walnut, according to mission scientists.

“We had an impression of Ultima Thule based on the limited number of images returned in the days around the flyby, but seeing more data has significantly changed our view,” said Alan Stern, the New Horizons mission’s principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute, in a Feb. 8 statement. “It would be closer to reality to say Ultima Thule’s shape is flatter, like a pancake. But more importantly, the new images are creating scientific puzzles about how such an object could even be formed. We’ve never seen something like this orbiting the sun.”

In the first few days after the flyby, scientists said they thought the object formed when two objects — which originally formed separately as the solar system was born 4.5 billion years ago — merged at a slow speed.

Scientists used a series of images captured by New Horizons as it departed Ultima Thule to estimate the object’s shape from the side. Imagery previously released showed Ultima Thule’s sunlit side from New Horizons on approach, but the departure sequence reveals a crescent Ultima Thule.

The shadowed side of Ultima Thule traced a path through a background star field, briefly blocking the light from the stars as New Horizons completed the flyby.

“This really is an incredible image sequence, taken by a spacecraft exploring a small world four billion miles away from Earth,” Stern said. “Nothing quite like this has ever been captured in imagery.”

The center frame of the 14 individual images used to create the video was taken by the spacecraft’s Long Range Reconnaissance Imager, or LORRI, telescopic instrument at 12:42 a.m. EST (0542 GMT) on Jan. 1, nine minutes after the probe’s closest approach to Ultima Thule. At that time, New Horizons was 5,494 miles (8,862 kilometers) from the object.

The telescopic camera was set to take images with relatively long exposure times due to the low light levels reflected off the crescent Ultima Thule, causing the individual frames to be blurred.

“While the very nature of a fast flyby in some ways limits how well we can determine the true shape of Ultima Thule, the new results clearly show that Ultima and Thule are much flatter than originally believed, and much flatter than expected,” said Hal Weaver, New Horizons project scientist from the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. “This will undoubtedly motivate new theories of planetesimal formation in the early solar system.”

Imagery and other data collected by New Horizons at Ultima Thule continues streaming back to Earth at about 1,000 bits per second, from a distance of more than 4.1 billion miles (6.6 billion kilometers). The final data from the flyby is expected to arrive on Earth in September 2020.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.