Imagery from NASA’s Dawn spacecraft, now in its closest orbit of the dwarf planet Ceres, reveal textures, landscapes and bright streaks possibly made of salts exposed by violent collisions with asteroids.

Dawn arrived in its low-altitude mapping orbit, the last of four types of orbits from which it studied Ceres, in early December. The spacecraft is currently flying 240 miles, or 385 kilometers, above Ceres, completing more than four laps of the cratered world every day.

Pictures captured by the Dawn spacecraft’s framing camera are four times sharper than imagery obtained from the mission’s last orbit, and NASA released samples of the photos Tuesday.

Dawn’s low-altitude observations at Ceres are the final chapter of a nearly decade-long mission that launched from Cape Canaveral in September 2007, reached the giant asteroid Vesta in 2011, then departed Vesta in 2012 to head for Ceres, a 590-mile-wide (950-kilometer) world that is largest resident of the asteroid belt.

“When we set sail for Ceres upon completing our Vesta exploration, we expected to be surprised by what we found on our next stop. Ceres did not disappoint,” said Chris Russell, principal investigator for the Dawn mission, based at the University of California, Los Angeles. “Everywhere we look in these new low- altitude observations, we see amazing landforms that speak to the unique character of this most amazing world.”

The craft returned more than 16,000 images of Ceres in 2015, from before its capture by the dwarf planet’s gravity in March through the start of the low-altitude mapping campaign in December.

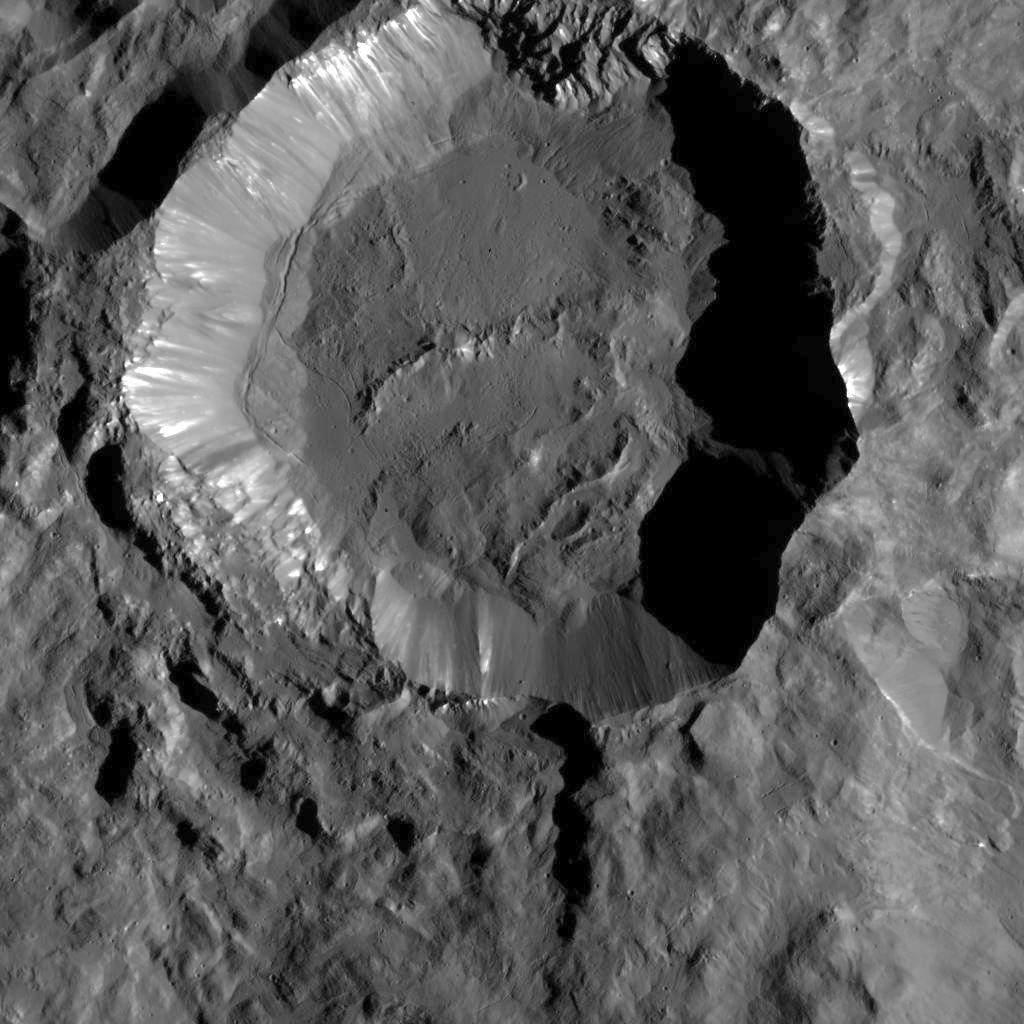

From its closest orbit to Ceres, Dawn has observed relatively young craters with rugged features, including Kupalo Crater, a 16-mile-diameter (26-kilometer) impact basin with a large, flat floor and bright streaks marking the crater walls.

“This crater and its recently-formed deposits will be a prime target of study for the team as Dawn continues to explore Ceres in its final mapping phase,” said Paul Schenk, a Dawn science team member at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston.

Scientists want to know whether the linear markings are related to Ceres’ bright spots in Occator Crater, which researchers believe are made of salts left over after the crater formed from an impact with a comet or asteroid.

Ceres likely has an underground layer of briny water-ice, and the frozen subsurface could be exposed by collisions with other space objects. Scientists think the ice sublimates, or changes from a solid to a gas, and escapes into space after it is brought to the surface by impacts, leaving the ice’s salt content behind.

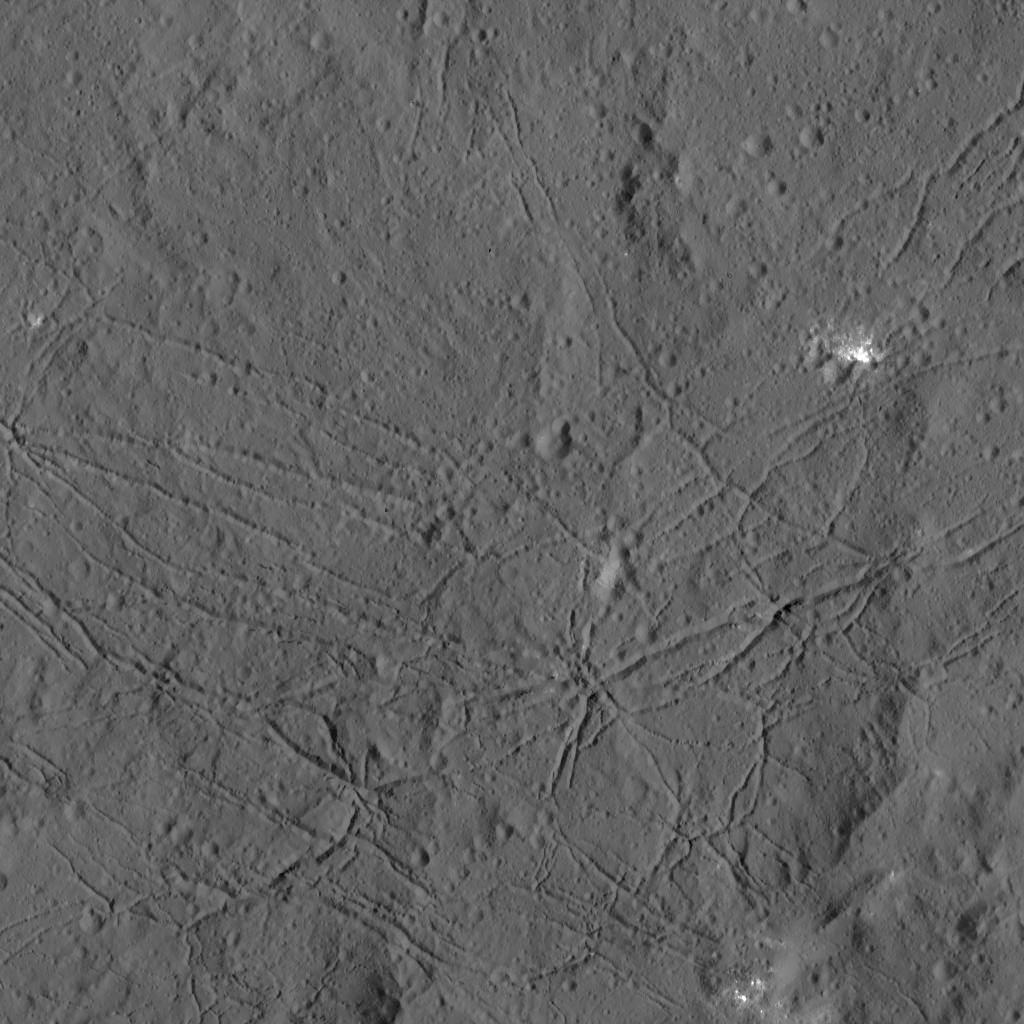

The scars of an ancient impact are also visible in the floor of Dantu Crater, another relatively young impact site on Ceres.

Fractures crisscross the floor of Dantu, and the features may have formed as melted rock heated by the impact cooled inside the crater. The moon’s Tycho Crater has similar cracks.

Dawn’s camera can see objects as small as 120 feet, or 35 meters, on Ceres from the probe’s current orbit.

Besides the imaging campaign, Dawn’s top scientific priorities over the next few months include mapping the chemical elements that make up surface of Ceres, and measuring the body’s gravity field.

Dawn is in the final six months of its primary mission, which ends June 30. The mission’s lifetime is limited by the spacecraft’s supply of hydrazine fuel needed to control the pointing of the probe.

Engineers powered up the spacecraft’s two remaining reaction wheels, which control Dawn’s orientation with momentum, in December to slow the consumption of hydrazine for the probe’s rocket thrusters. Two other reaction wheels failed earlier in the mission, prompting officials to devise a backup plan to continue flying the spacecraft without them.

As long as Dawn’s reaction wheels are operational, engineers buy more time for the mission by conserving hydrazine. Even with the wheels switched on, the spacecraft still needs hydrazine fuel some pointing maneuvers.

Ground controllers plan to leave the spacecraft in its current orbit after the mission is complete.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.