A United Launch Alliance Delta 2 rocket fired away from a California military base and disappeared into an overcast cloud deck Saturday on its final flight, carrying a NASA research satellite into orbit and closing the book on a nearly 30-year legacy of launches.

The 128-foot-tall (39-meter) rocket lit its kerosene-fueled Aerojet Rocketdyne RS-27A main engine at 6:02 a.m. PDT (9:02 a.m. EDT; 1302 GMT), then ignited four Northrop Grumman-built strap-on solid rocket boosters a few seconds later to propel the Delta 2 off its launch pedestal at Vandenberg Air Force Base, California.

Riding roughly 650,000 pounds of thrust, the Delta 2 rocket — emblazoned in its iconic bluish-green paint scheme — disappeared into low clouds, but long-range infrared tracking cameras followed the launcher’s progress as it pitched to the south from Vandenberg, a military-run spaceport on California’s Central Coast northwest of Los Angeles.

The four solid rocket boosters burned out and jettisoned to fall into the Pacific Ocean less than 90 seconds after liftoff, and the first stage’s RS-27A main engine — tracing its design heritage to NASA’s Saturn 1 and 1B rocket programs of the 1960s — shut down for the final time at T+plus 4 minutes, 24 seconds.

After releasing the first stage, the Delta 2’s second stage Aerojet Rocketdyne AJ10-118K engine fired for the first of four burns on Saturday’s mission, then shut down at around the 11-minue point of the flight. The Delta 2 coasted over Antarctica, then headed north over the Indian Ocean before reigniting the upper stage engine for less than 7 seconds to circularize its orbit.

NASA’s ICESat 2 satellite, kicking off a $1 billion mission using lasers to measure global ice sheet changes from space, deployed from the rocket’s upper stage around 53 minutes after liftoff. A live video view beamed down from the Delta 2 showed the 3,340-pound (1,515-kilogram) NASA research craft flying away from the rocket against the inky black backdrop of space.

ULA programmed the rocket to release ICESat 2 in an orbit nearly 300 miles, or about 474 kilometers, above Earth. Delta 2 flight commentator Patrick Moore confirmed the rocket achieved an orbit very close to pre-flight predictions.

ICESat 2, built by Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems, unfurled its solar panel shortly after separating from the Delta 2, commencing a 60-day commissioning schedule before starting regular scientific observations of land and sea ice in November.

Another burn by the Delta 2’s AJ10 second stage engine slightly adjusted its orbit to set up for the separation of four CubeSats developed by university students. The CubeSats launched on Saturday’s mission were:

- ELFIN, or the Electron Losses and Fields Investigation, a space weather mission developed at UCLA using three scientific instruments in a 3U+ CubeSat form factor.

- ELFIN-STAR, also from UCLA,, an identical 3U+ CubeSat that will allow scientists to more precisely measure the radiation environment in low Earth orbit.

- DAVE, or the Damping and Vibrations Experiment,, a 1U CubeSat developed at Cal Poly with a payload to evaluate a mechanical damping technology in microgravity.

- SurfSat, a 2U CubeSat developed at the University of Central Florida to measure static charging on spacecraft surfaces in orbit.

Meanwhile, the Delta 2 upper stage fired once more for a braking burn to drop out of orbit and re-enter Earth’s atmosphere over the Pacific Ocean, where the rocket was expected to break apart and burn up. The deorbit burn was intended to ensure the mission does not add more space junk to orbital traffic lanes, and the re-entry marked the formal conclusion of the final Delta 2 flight.

“I’m a little bit sad,” said Tim Dunn, NASA’s launch director for the ICESat 2 mission. “I’m thrilled with mission success, and that we were able to close the chapter on Delta with a huge success of an incredibly important science payload.

“ICESat 2 is going to do cutting edge scientific data-gathering, the precision measurements it’s going to do from space are just going to be incredible,” said Dunn, a 22-year veteran of the Delta 2 rocket program at Boeing and NASA. “So to be able to say that we launched this very important science mission on the final flight of the industry workhorse is just a huge accomplishment for the entire team. I have a lot of personal feelings about the Delta 2, but I’m really just a very small part of the entire Delta 2 team.”

While ULA’s Delta 4 rocket will remain in service for several more years, the Delta 2 rocket was the last U.S. launcher flying that could trace its basic design to the dawn of the Space Age.

When the first Delta 2 rocket took off on Valentine’s Day 1989, ideas like navigating by smartphone and driving robots on Mars were science fiction. More than 150 launches over the last 30 years helped change all that.

The first launch of a Delta rocket occurred in May 1960, debuting a derivative of the Thor intermediate range ballistic missile capable of putting a satellite into orbit. Engineers have lengthened the Thor’s original 8-foot-diameter (2.4-meter) first stage several times, expanding the Delta’s propellant capacity, while adding a new upper stage engine and strap-on solid rocket boosters to haul heavier payloads into space.

The Delta rocket line has been on the brink of retirement several times, perhaps most notably in the 1980s, when the U.S. government sought to transition all of its satellite launches to the space shuttle. That policy changed in the aftermath of the Challenger accident in 1986, resulting in the creation of the Delta 2 and the restart of the Delta production line.

Read our earlier story for the recollections and thoughts of several Delta 2 launch veterans.

The more powerful Delta 4 rocket will continue flying for ULA, taking the Delta name into the 2020s, but it is also due for retirement in the early-to-mid-2020s.

The Delta 4 is a new design, incorporating different hydrogen-fueled engines, and wider propellant tanks than the Delta 2. Boeing, which ran the Delta program in the late 1990s, designed the Delta 3 rocket as a bridge between the older and new members of the Delta family, utilizing the Delta 2’s Thor-based first stage and the Delta 4’s new upper stage.

Delta 2s, which sometimes lifted off two or three times per month in the 1990s and 2000s, have been replaced by a fleet of bigger launchers. ULA moved on to focus on the Atlas 5 and Delta 4 boosters, and SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket now carries up many of the same types of payloads that were once tailored for the Delta 2.

Many commercial and military missions once served by satellites sized to fly on the medium-lift Delta 2 launcher are now accomplished by smaller spacecraft, taking advantage of the miniaturization trend in technology. At the opposite end of the mass spectrum, many commercial communications satellites outgrew the Delta 2’s capabilities in the 1990s and 2000s.

Delta rocket technology also made its way into Japan’s space program, which used license-built Thor-derived first stages and AJ10 upper stage engines on Japanese launchers in the from the 1970s through the early 1990s, before switching to domestic designs.

In its configuration with nine solid rocket boosters, a Delta 2 could put more than 6,600 pounds (3,000 kilograms) of payload to an orbit 517 miles (833 kilometers) above Earth.

Delta 2 rockets successfully launched 48 satellites for the U.S. Air Force’s Global Positioning System from 1989 through 2009, a two-decade span during which the satellite network became a part of the everyday lives of billions of people worldwide.

“Supporting the Air Force through all those years, that’s a special memory with GPS,” Dunn said. “From 1989 when GPS 2-1 first launched, as you progressed through the ’90s, that was the time when GPS went from this military system that only the military used, to essentially a common everyday person’s utility. That was really fun to be supporting and sustaining the constellation that everyone was beginning to use. Fast forward to 2018, and (when) you talk to younger kids today about GPS, they can’t imagine life without GPS, on your phone, on your watch, in your car.”

The GPS fleet consists of more than 30 satellites, and more than half of the GPS spacecraft currently in orbit were launched by Delta 2s. The network is vital for civilian navigation, from families on road trips, to hikers, to airliners landing in low visibility.

“Every single person who turns on their map on their telephone to get around, that GPS constellation is pretty amazing,” said Scott Messer, ULA’s Delta 2 program manager. “The constellation itself is super-amazing, but it’s certainly been a thrill from the Delta 2’s standpoint to launch that and be part of what enabled that.”

Here are some statistics on Saturday’s launch:

- 381st Delta rocket launch since 1960

- 724th launch of a Thor-based rocket

- 237th Delta launch with NASA involvement

- 155th Delta 2 rocket mission since 1989

- 14th Delta 2 to fly in the 7420 configuration

- 241st flight of an RS-27 engine

- 277th flight of an AJ10 engine

- 1,000th-1,003rd GEM-40 solid rocket motors launched on Delta 2s

- 54th Delta 2 mission overseen by NASA

- 45th Delta 2 rocket launch from Vandenberg Air Force Base

“The Delta 2 vehicle has touched the life of probably every single person in America in the technoloy that it’s enabled over its 30 years,” Messer said. “It’s been a very, very prominent part of space history.”

Other Delta 2s dispatched NASA’s first three Mars rovers — Sojourner, Spirit and Opportunity — toward the red planet, along with the MESSENGER mission to orbit Mercury, the Dawn mission to the asteroid belt, the Spitzer Space Telescope, the planet-hunting Kepler observatory, weather satellites, and dozens of commercial and military communications spacecraft.

From Vandenberg, Delta 2 rockets hauled the bulk of Iridium’s first-generation fleet of voice and data relay satellites into low Earth orbit on 12 launches from 1997 through 2002. Those satellites are now being replaced by an upgraded Iridium fleet launching on SpaceX Falcon 9 rockets.

The Globalstar satellite network, also designed for mobile communications, was deployed by a series of Delta 2 rockets launched from Cape Canaveral.

Saturday’s launch extended the Delta 2’s record to 100 successful launches in a row, a streak dating back to Jan. 17, 1997, when the workhorse suffered one of the most memorable rocket failures of the last quarter-century. A Delta 2 exploded just 13 seconds after a launch from Cape Canaveral with a GPS satellite, raining debris back down on its launch pad, leaving a cratered parking lot and destroyed cars outside the pad bunker.

No one was injured in the accident, and the Delta 2 returned to flight less than four months later with an Iridium satellite launch from California.

“The Delta 2 will go down in history as one of the world’s most successful launch vehicles, and we’re proud to be part of that legacy,” said Eileen Drake, CEO and president of Aerojet Rocketdyne, supplier of the Delta 2’s first and second stage engines.

The RS-27A main engine, which generates 200,000 pounds of thrust at sea level, is a descendant of the H-1 engine used on the main stages of NASA’s Saturn 1 and Saturn 1B rockets, the predecessors of the Saturn 5 moon rocket in the Apollo program. In addition to a main thrust chamber, the RS-27A has two vernier engines for roll control during flight.

The second stage’s AJ-118K engine has its roots in the ballistic missile programs of the 1950s, and was later updated to power the Transtage, an upper stage that flew on Titan rockets, according to Aerojet Rocketdyne. It burns a combination of Aerozine 50, a fuel cocktail made by mixing hydrazine and unsymmetrical dimethyl-hydrazine, and nitrogen tetroxide oxidizer to provide 9,850 pounds of thrust at altitude.

Elizabeth Jones, Aerojet Rocketdyne’s RS-27 and AJ10 program manager, said Friday that the Delta 2’s engines went through several upgrades over the decades, adding thrust and performance as the rocket’s size crew larger. Both types of engines will not fly again after Saturday’s mission, but a similar engine to the AJ10 will continue launching with NASA’s Orion crew capsule.

“We’ve been saying at some of our meetings, who’s going be the first one to crack? Is anybody going to tear up? It’s an emotional time, there’s a long legacy to be proud of,” Jones said.

“I’ll miss the work, I’ll miss the people,” said Latanjia Robinson, Aerojet Rocketdyne’s AJ10 chief engineer. “I’ll miss traveling to the launch sites to support the various tasks prior to launch, and the launches themselves.

“But it’ll be rewarding. I look forward to a successful mission,” Robinson said in an interview before Saturday’s launch.

The Delta 2 could fly with three, four or nine solid rocket motors built by Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems, formerly known as Orbital ATK. Over the history of the program, more than 1,000 of the solid motors have launched with Delta 2 rockets.

Other holdover practices from the early Space Age that continued with the Delta 2 included a manual command from the control center to start the RS-27A main engine. Delta 2 countdowns didn’t use an auto sequencer like newer rockets.

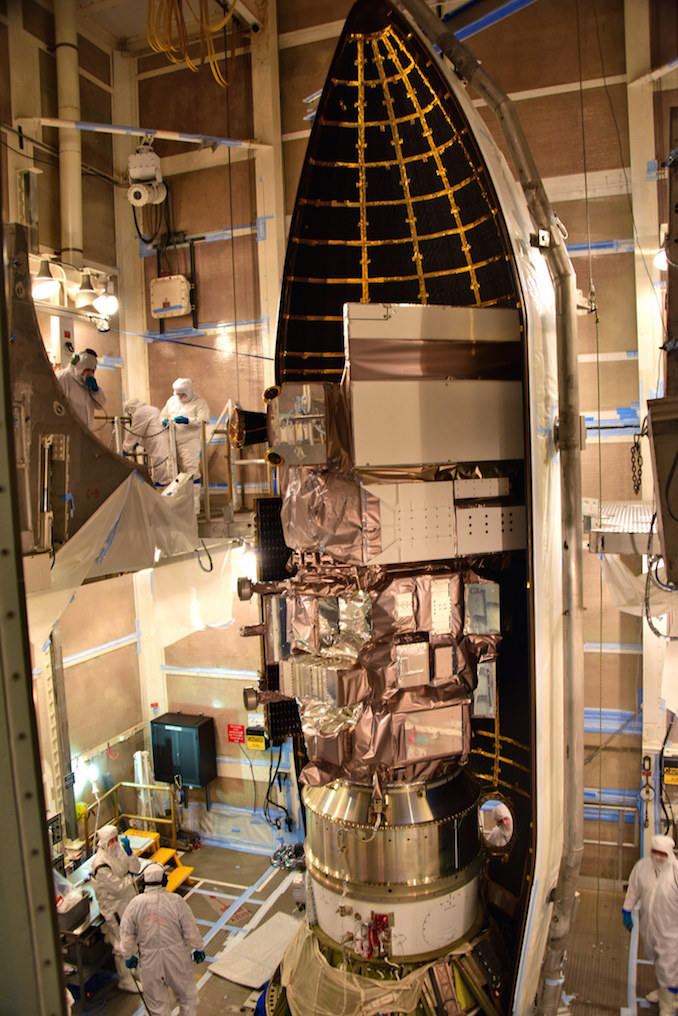

The Delta 2’s payloads were encapsulated inside the rocket’s nose cone on top of the launch pad’s mobile gantry in a cramped clean room, whereas satellites riding newer U.S. launchers are closed up inside their fairings in more expansive offsite processing facilities, then transported to the pad.

The Delta 2’s color was also a standout among the world’s roster of rockets.

While early Delta rocket variants were painted white, officials decided in the early 1970s to save weight by not painting the vehicle. The weight savings translated into more lift capability for the Delta rocket, and subsequent launches flew with the underlying primer, dubbed “Delta Blue,” according to Collectspace.com.

“That baby blue paint scheme,” Dunn said in an interview with Spaceflight Now. “I’m going to miss that because I don’t see another rocket out there painted in baby blue just yet, but maybe there will be one coming.”

ICESat 2 begins ice-surveying mission

ICESat 2 stands for Ice, Cloud and land Elevation Satellite 2, a follow-on to NASA’s ICESat mission which measured global ice sheets from 2003 until 2009.

Featuring an improved laser instrument designed to provide more precise measurements than its predecessor, ICESat 2 will extend a data series which has shown ice is melting around the edges of Greenland and Antarctica, and is thinning in the oceans.

“What we learned from ICESat about the ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica is that they are particularly losing ice around coastal areas, which means, one, that they were losing ice, and also two, it was probably tied to changes occuring in the ocean,” said Tom Wagner, NASA’s cryosphere program scientist.

That’s important because ice conditions are linked to other factors that drive Earth’s climate, such as currents and temperatures in the oceans. And rising sea levels could threaten cities along coastlines, according to scientists.

“In Antarctica and Greenland, we have about two-thirds of the Earth’s fresh water,” said Helen Fricker, a member of ICESat’s science definition team at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. “If all of that ice melted, we would raise global sea level on average by about 180 feet (54 feet), which is very significant.”

Altimetry data collected by by the U.S.-French TOPEX/Poseidon and Jason series of satellites show the average global sea level rose by 77 millimeters (3 inches) from 1993 through 2017. Scientists will compare data from missions like ICESat 2 with gravity measurements from missions like GRACE-Follow On, which launched in May and is sensitive to the mass of the ice.

“ICESat 2 really is a revolutionary new tool for both land ice and sea ice research,” said Tom Neumann, ICESat 2’s deputy project scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Read our earlier story for a detailed report on ICESat’s science objectives.

NASA has used satellites to look at ice for decades, but tracking ice coverage is easier than measuring the height, and estimating the thickness, of floating sea ice and ice caps covering land masses.

Rather than relying on a single laser beam, as ICESat did, the new mission will fire six laser beams down to Earth and measure the time it takes for the light to bounce off the surface and back to a telescope on-board the spacecraft. The results will yield information on the height and slope of the ice.

The ICESat 2 satellite was built by Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems, and its single instrument — the Advanced Topographic Laser Altimeter System, or ATLAS — was developed at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

“ATLAS essentially acts like a stop watch,” said Donya Douglas-Bradshaw, ATLAS instrument manager at Goddard. “The ATLAS laser fires 10,000 pulses per second with a trillion photons in each shot. Each time the laser fires, it starts the stop watch. It takes about 3.3 milliseconds for the beam to exit the instrument, reach the surface and return back to the telescope.”

Only about a dozen or so photons will make it back to ICESat 2’s receiving telescope, with the rest of the light scattering in the atmosphere or back into space.

The laser package “has the ability to time tag a single photon to billionth of a second accuracy,” Douglas-Bradshaw said in a briefing with reporters. “This precision allows the instrument to detect annual changes in ice elevation on the order of half of a centimeter (0.2 inches).”

The photon-counting method is new, and development the ATLAS laser proved to be a challenge, delaying ICESat 2’s launch more than two years, and adding several hundred million dollars to the mission’s cost.

Ground controllers plan to open a protective door covering the ATLAS instrument’s sensitive optics around a week after launch, followed by the switch-on of the ATLAS laser about a week after that, according to Doug McLennan, ICESat project manager at Goddard.

After around 60 days of commissioning, officials expect to declare ICESat 2 ready for science observations.

ICESat is designed for a three-year mission, but it carries enough fuel to remain useful for more than 10 years, McLennan said.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.