The NASA manager overseeing development of Boeing and SpaceX’s commercial crew ferry ships says the space agency has approved SpaceX’s proposal to strap in astronauts atop Falcon 9 rockets, then fuel the launchers in the final hour of the countdown as the company does for its uncrewed missions.

The “load-and-go” procedure has become standard for SpaceX’s satellite launches, in which an automatic countdown sequencer commands chilled kerosene and cryogenic liquid oxygen to flow into the Falcon 9 rocket in the final minutes before liftoff.

“From a program standpoint, we went throgh a pretty extensive process where we laid out the different options for loading the crew, and assessing how the vehicles have been designed, and what the trades were,” said Kathy Lueders, NASA’s commercial crew program manager, in an interview Friday. “That came to the program in June, and after looking at it, we felt like the current baseline plan for how SpaceX plans to load the crews meets our requirements.”

Other liquid-fueled rockets, such as United Launch Alliance’s Atlas 5 launcher, typically receive their propellants earlier in their countdowns. The Atlas 5, which will be used to launch Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner capsule, consumes the same propellants as the Falcon 9.

But SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket, which will power the company’s Crew Dragon spacecraft into orbit with astronauts on-board, burns a mix of kerosene and liquid oxygen chilled to near each fluid’s freezing point. The densified propellant allows more fuel to be loaded into the Falcon 9’s tanks, and it gives the rocket’s Merlin engines a thrust enhancement.

Filling of the Falcon 9 rocket in the final stages of the countdown is timed to give the super-chilled propellant minimal time to warm up before liftoff, which would reduce the rocket’s lift capability.

On some more demanding launches, the lost lift capacity from warmed propellant would prevent the Falcon 9 from satisfying mission requirements.

On crewed launches, ULA plans to finish loading propellant a couple of hours before liftoff, then slowly replenish liquid oxygen as it boils off in the warm ambient environment on Florida’s Space Coast. Ground support crews will help the astronauts board the CST-100 crew capsules, then evacuate the pad for the terminal countdown.

The space shuttle followed a similar pre-launch timeline, with fueling occurring first, followed by the strap-in of the astronauts.

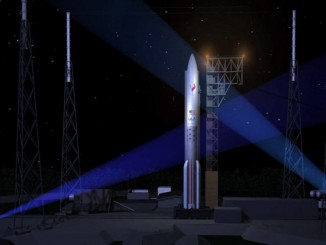

SpaceX proposed using its normal countdown timeline, which calls for propellant loading to commence at T-minus 35 minutes with the company’s Falcon 9 Block 5 rocket, the same model that will be used for crewed launches.

Astronauts will be in their seats, the Crew Dragon’s hatch will be closed, and the closeout team will be a safe distance away from launch pad 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center before fueling begins.

“Our teams have been following along with their normal operations, so we have a pretty good understanding of how their vehicle operates,” Lueders said. “That also really helped us in the assessment because we really understand now why SpaceX was doing what they’re doing. Even though it looks different, it’s different because it’s not the shuttle.

“There are things that you could do with the shuttle. There were recirculation pumps and stuff like that that you can’t do with the SpaceX vehicle,” she said. “So it’s really about understanding the differences in the vehicles, and how each one flies the best. That really helped us with that decision.”

SpaceX’s “load-and-go” procedure raised concerns after a Falcon 9 rocket exploded on its launch pad at Cape Canaveral in September 2016. The fiery accident occurred in the final minutes of a countdown while propellants were flowing into the rocket before a hold-down engine firing, destroying the launcher and an Israeli-owned communications satellite on-board.

Officials from SpaceX said the Crew Dragon’s escape system, comprising a set of high-thrust SuperDraco engines around the circumference of the capsule, would be quick enough to push the spacecraft and its crew away from such an explosion during fueling.

The abort thrusters will be activated and armed before fueling of the Falcon 9 during crewed launches.

SpaceX is also redesigning high-pressure helium tanks, or composite overwrapped pressure vessels, blamed for the September 2016 accident.

SpaceX engineers believe that failure most likely started when liquid oxygen propellant froze in a buckle or void between the aluminum liner and carbon overwrap of one of the COPVs. While investigators were unable to pinpoint a “root cause,” engineers concluded the solid oxygen likely ignited from friction or breaking fibers on the outside of the helium tank, causing the Falcon 9’s upper stage to burst in a ball of flame.

SpaceX modified its fueling and helium loading procedures after the September 2016 accident to prevent solid oxygen from forming, and a new COPV design incorporates changes the company says will eliminate the buckles altogether.

The company has completed development, significant qualification testing and manufacture of the modified helium bottles that will fly inside the Falcon 9 rocket on the Demo-1 mission with the Crew Dragon spacecraft.

A previous Falcon 9 launch failure in June 2015 was most likely caused by a substandard strut inside the rocket’s second stage liquid oxygen tank, which freed one of the helium COPVs inside the stage and ruptured the tank. SpaceX says it has changed the type of mounting brackets used for the COPVs to resolve that concern.

SpaceX has accomplished 33 consecutive successful rocket launches since the Falcon 9 resumed service in January 2017.

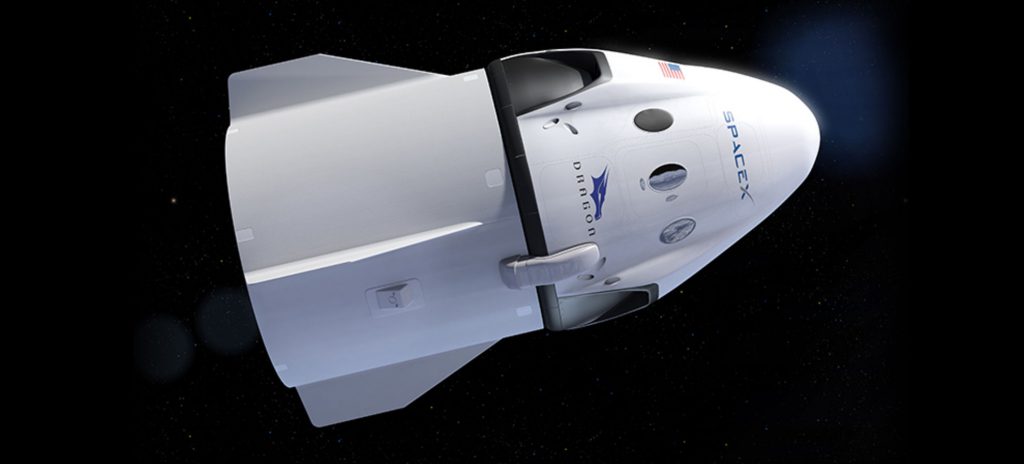

The Demo-1 mission is an unpiloted test flight of the Crew Dragon scheduled for launch in November. SpaceX plans to follow that with the Demo-2 mission in April 2019, with NASA astronauts Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken on-board on a flight to the International Space Station.

The Demo-2 test flight is expected to last a couple of weeks, and Hurley and Behnken will come back to Earth inside the Crew Dragon with a parachute-assisted splashdown at sea.

Lueders said Friday that the Demo-2 crew test flight will be preceded by about a month by an in-flight abort demonstration, in which SpaceX will launch a Crew Dragon on a test version of the Falcon 9 and command its abort thrusters to fire the capsule away from the launcher about a minute after liftoff.

The in-flight abort will test Crew Dragon’s ability to get the crew away from a launch failure during the period of flight with the most intense aerodynamic pressures. SpaceX conducted a Crew Dragon pad abort test in 2015 to simulate escaping from an accident on the launch pad.

NASA awarded SpaceX and Boeing contracts valued at $2.6 billion and $4.2 billion, respectively, in 2014. Once each company accomplishes their uncrewed and crewed test flights, they will begin regular crew rotation missions to and from the space station, ending U.S. reliance on Russian Soyuz ferry craft for astronaut transportation.

Lueders said NASA engineers will continue following SpaceX countdowns to ensure the Falcon 9 fueling procedure is safe before permitting astronauts to fly it.

Members of NASA’s Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel said during a meeting in May that the load-and-go procedure could be acceptable.

Brent Jett, a former space shuttle commander and member of the safety panel, said during the meeting that a report completed by the NASA Engineering and Safety Center provided the safety committee and NASA managers “an in-depth analysis of the hazards and controls associated with load-and-go.”

“This report, which identified a few previously unrecognized hazard causes, proved very valuable to the commercial crew program,” Jett said in the safety panel’s May 17 meeting at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

“My sense is that, assuming there are adequate, verifiable controls identified and implemented for the credible hazard causes, and those which could potentially result in an emergency situation, or worse, loss of crew and vehicle, it appears that load-and-go is a viable option for the program to consider,” Jett said.

Other members of the panel agreed with Jett’s assessment.

“It appears that if all the approriate steps are taken to address the potential hazards, that the risk of launching the crew in the load-and-go configuration could be acceptable,” said Patricia Sanders, chair of the ASAP.

“The other important factor as NASA considers recommendations on this topic, I think, is to look at this from a system point-of-view,” said George Nield, former head of the FAA’s commercial space office and now an ASAP member. “So not only crew safety, but also ground crew safety is an important factor.”

Musk told reporters in May that he thinks the load-and-go fueling question is “overblown.”

“We certainly could load the propellant, and then have the astronauts board Dragon,” Musk said. “That is definitely something we could do. But I don’t think it’s going to be necessary any more than passengers on an aircraft having to wait for the aircraft to be full of fuel before boarding.

“Obviously, our competitors are going to make hay of it, but I do not see this as a risk representing any materiality, and in a worst-case scenario, we’ve already demonstrated that Dragon is fully capable of a safe abort from zero velocity and zero altitude, and escaping whatever fireball may occur on the pad in a worst-case situation,” Musk said.

A recent report by the Government Accountability Office identified several technical risks facing SpaceX and Boeing, including the COPV issue on the Falcon 9, and concerns about the CST-100 Starliner’s stability during a launch abort.

Lueders told Spaceflight Now that NASA and its commercial crew contractors “still have some residual work” to resolve the technical issues.

“But we have plans for closing out all of them,” she said. “I think our biggest challenge, from a schedule perspective, for both providers right now is getting all our parachute testing done.”

According to Lueders, Boeing and SpaceX are conducting drop tests to complete qualification of the parachutes. While SpaceX’s Crew Dragon will splash down at sea, Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner will come back to Earth under parachutes for airbag-cushioned landings in the Western United States.

“Both of them are in their qualification campaigns right now, and we have just a couple of flights left on that,” she said. “And then we have some additional reliability tests that we would like to get done.”

Boeing and SpaceX could launch their uncrewed test flights before formally resolving some of their technical concerns, but Lueders said all of the engineering issues must be closed out before a crewed test flight.

“We could learn something on the uncrewed demo and need to change the configuration,” she said. “We want to make sure that we’re getting enough testing done (before the uncrewed demo flights) to make sure that the vehicle is going to be safe to dock with station and return, but not all the testing thats required for a crewed flight test needs to be done for an uncrewed flight test.”

SpaceX first space-worthy Crew Dragon vehicle, slated to fly the unpiloted Demo-1 mission in November, arrived at Cape Canaveral last month for final launch preps. The Falcon 9 launch vehicle, the first to incorporate the redesigned helium COPVs, is scheduled to depart SpaceX’s factory in Hawthorne, California, for stage testing at the company’s Central Texas test site this month, Lueders said.

Components of the Falcon 9 rocket for the Demo-1 mission are scheduled to arrive at the Florida launch base in September, she said.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.